Journal Entries

Bonsai is largely a matter of time.

Time, not in the sense of an impressive number, as in how many years old is this tree here or that tree there, but time as in what it takes to see, feel, absorb, learn, and finally understand. It will take time to explain about bonsai at The North Carolina Arboretum and how it came to be the way it is. Over time, the Curator’s Journal will provide the answers.

Click on individual posts below, arranged from newest to oldest, to explore more than three years’ worth of journal entries on bonsai at The North Carolina Arboretum with writing and photography by Arthur Joura.

Year Four

At this juncture, it might be said that the tree has been given a new design. Such a statement is true only to the extent that the new design is understood to be in transition. The design idea is not locked in. In naturalistic bonsai, the design process is both incremental and collaborative. In naturalistic bonsai design the tree’s agency is recognized and respected; the tree is partner to the design process.

In writing this composition, as in writing many of the entries in the Curator's Journal, I am giving my remembered first-hand account of events in which I was an active participant. That makes me an eyewitness, although hardly an objective or unbiased one. But it is precisely because this particular story is so personal to me that for the past few years I have felt a growing desire, and even a need, to write it down.

When the deliberations went on for months, I thought the Arboretum's hesitancy excessive. How much was there to think about? Say yes or say no, but make a decision so we can all move on. As the last few days of December passed and the deadline drew near and still no answer came, I began to feel pessimistic, like maybe an answer wasn’t going to come. No answer would be the same as saying no.

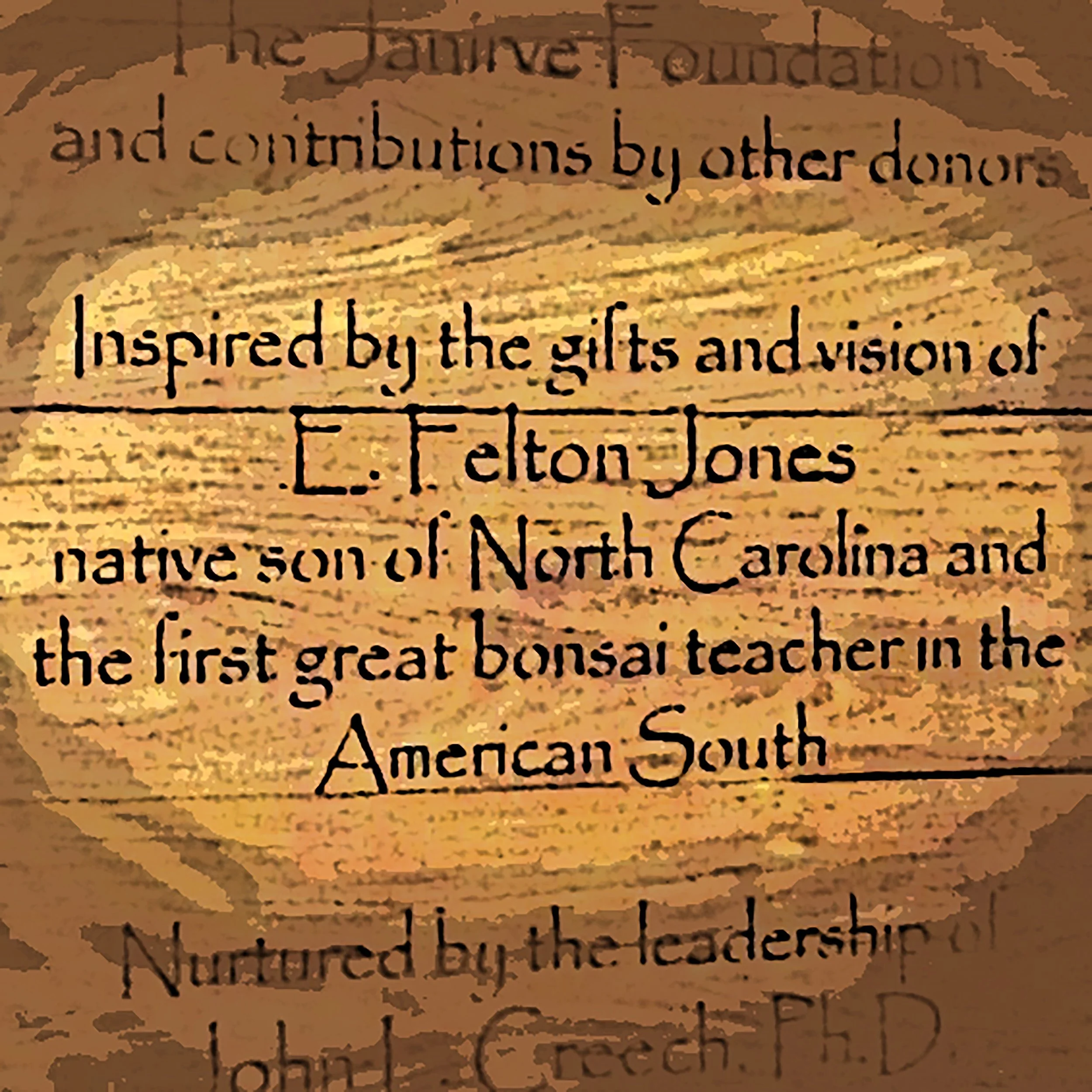

When I first heard of Felton's proposed donation I immediately assumed he must have reached out to some of those former students of his that he claimed were financially well-off and ready to help out if he asked them to. This proved to be an incorrect assumption. The money was Felton's, from a bank account apparently no one knew he had.

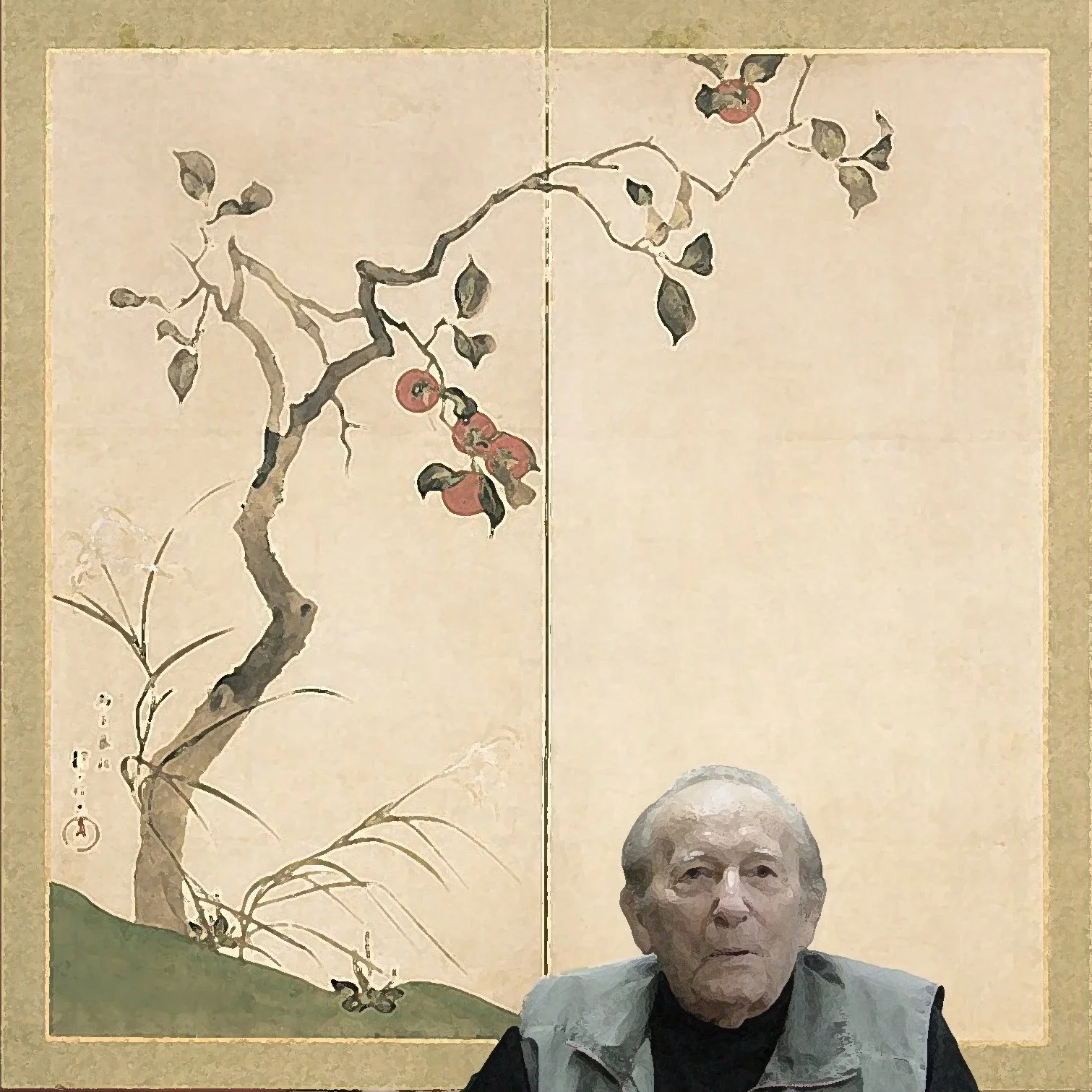

Something in the old, traditional Japanese ways resonated with Felton and soon he was seeing nature through that lens. Bonsai captured his imagination in a visceral way. But he was also attracted to Japanese gardens and ikebana, and Japanese sumi paintings of nature, and Japanese haikus about nature. In fact, everything that might be construed as traditional Japanese appealed to Felton, whether it related directly to nature or not.

Long before there was Christmas, long before there was Hanukkah, long before there was a recorded history of humankind, this time of year was of singular importance in the consciousness of our forebears living in the Northern Hemisphere.

I saw Felton as something of a wanderer, someone who sometimes got an itch to head on down the road somewhere and if he liked where he found himself he might stay put for a while. Sooner or later, though, he was bound to move on. That's how it was until the end, when Felton was old and broken down, more or less stuck in Durham, and that was the period in which I knew him.

This week’s entry once again features a video derived from the online educational programs offered during the shutdown of 2020. This program focuses on the concept of naturalism as it applies to the shaping of little trees, a subject of great importance to bonsai at The North Carolina Arboretum. This program provides a good introductory overview of the concept and the way it has played out with some of the trees in our collection.

The day before the bonsai were removed, I took my camera and made one last walk through the garden to photograph them. We had forty one specimens on display and I captured an image of each. They are presented to you here, along with a note that I photographed them as I found them. The trees were not cleaned up in any way. What you see as you look at these pictures is just how the garden display would have been if you walked in that last day for one final look.

I made contact with Felton on my first visit with the Triangle Bonsai Society in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1995. He was that group's resident sensei and he would have been about seventy four years old at the time. I had heard his name before that, though, because it seemed all the bonsai people of the day knew Felton.

When I'd ask people what they meant by wabi-sabi their definitions were vague or squishy, and then one day somebody told me that it was a Japanese thing and most Westerners could never understand it. That sealed it for me. I put wabi-sabi aside in a big box where I kept all that sort of stuff and decided I shouldn't waste time worrying about something I probably could never understand anyway.

It never comes all at once. Photos of autumn color in the landscape, and the memories of autumn’s glories we keep in our minds, typically capture the peak of the season. This is only one phase of autumn, however, a fraction amounting to a few days.

Cast your mind back to 2020, the year the Covid-19 pandemic changed everything about the way we live. The North Carolina Arboretum, like every other public institution in the world, had to react and adapt to the strange new reality of people avoiding social contact.

Even after a prolonged meditation on how to go about rebuilding this landscape, at the start of the demonstration I still didn't have a clear vision of how the composition would come together. I had a vague idea of what might happen, but that little bit of a clue proved to be incorrect.

If you plan on doing work that requires any real thought, any consideration of possibilities, forget it, a live demonstration is the worst way to go. Doing creative bonsai work by the clock is not a good idea. It might well be that most decisions in life get made with one eye on the clock, and maybe a lot of those decisions would never get made at all if it wasn’t for the clock, but creativity shouldn’t be constrained that way.

You could never do that. You'd go out of your mind... but that's the point, right? Out of your mind. Leave your mind behind, leave thinking behind, live in the moment and be here now. Yeah, listen to you. What's the secret of life oh great guru?

But beyond being an artist Zhao was also proof of something, a living example of a fact you thought must be true but couldn't prove. There had to be multiple ways of going about it — had to be. If the whole little tree business was truly an art form then there couldn't be just one right way. Art doesn't work like that.

The baldcypress water-and-land planting Mr. Zhao made for us in his 1998 demonstration program was remarkably good right from the time he put it together. It had a great feeling to it, a kind of authenticity that evoked the experience of being in nature, somewhere in the hushed coniferous forest where the sound of water splashing on rock is so persistent it ceases to be noticeable.

In America Mr. Zhao was best known in those days for one of his tray landscape plantings done in the water-and-land penjing style. The landscape depicted a scene wherein horses are resting in the shade of flowering trees, with picturesque boulders strewn about and a stream nearby. This penjing was titled: Painting With Eight Horses.

Right from the beginning, the redcedar that came to be called Crazy Horse was thought the better of the two, its claim to superiority based on having a fantastic display of deadwood in its trunk. The other redcedar also had an old trunk with deadwood, yet it lacked the extravagant flair of its counterpart. The trunk of this lesser tree was long, thin and scraggly in appearance.

There was also a noticeable degree of creep taking place in the top of the tree. “Creep” is the term I use for changes naturally occurring in small increments over an extended period of time that aren’t initially recognized. Then one day you see plainly that things have changed and wonder how long it’s been going that way.

As the bonsai collection began to gradually increase and improve, it attracted ever more attention from the public. Before long, when visitors wandered through the Support Facility workspace, they would find me or one of the bonsai volunteers working on little trees and this activity always pulled people in. The volunteers and I would energetically engage the visitors, talking up the bonsai program and eagerly answering the many questions people had.

Memes are units of cultural information that are spread by imitation. In this way of thinking, language, writing, reading, art, music, dance, sports and exercise are all memes, as are literally countless other human activities not having to do with biological survival. Eating is not a meme, but farming, cooking and using utensils all are. If it has to do with culture, not biology, it's made of memes.

Kathy knew what to do. She selected two parts of the elm that looked promising and proceeded to air-layer them. One of the two air-layers was successful and Kathy then severed it from the parent tree and planted it in its own pot. She then began to style this new tree to give it a pleasing bonsai shape.

Tray landscapes give the viewer a helping hand by providing a little more information. The inclusion of multiple trees, shrubs, stones, and other components creates a more fully described image. This makes it easier for the viewer to do what they are supposed to do when contemplating any bonsai, which is to shrink themselves down to the correct size and step into the picture.

I thought the game was over, but the tree didn’t. All the other parts of the oak were still good, still growing, still strong. That tree still wanted to live and I wasn’t going to be the one to tell it otherwise.

By intention, the bonsai garden is a place where reality is meant to be set aside for a short time. The garden creates an environment conducive to magic. The magic is not inherent in the garden, but is brought in there by the visitors who enter. The visitors walk in carrying with them their own unique set of experiences and, hopefully, their imaginations.

That which is thought to be optimal is often enough at odds with reality. We might have a plan that anticipates a certain course of events, but that can never be anything more than a starting point, after which things go the way they go due to circumstance. Mitigating factors in the world of bonsai growth and development include, but are not limited to: Weather conditions, incidence of disease and pest damage, accidents, mistakes, poor timing and availability of labor.

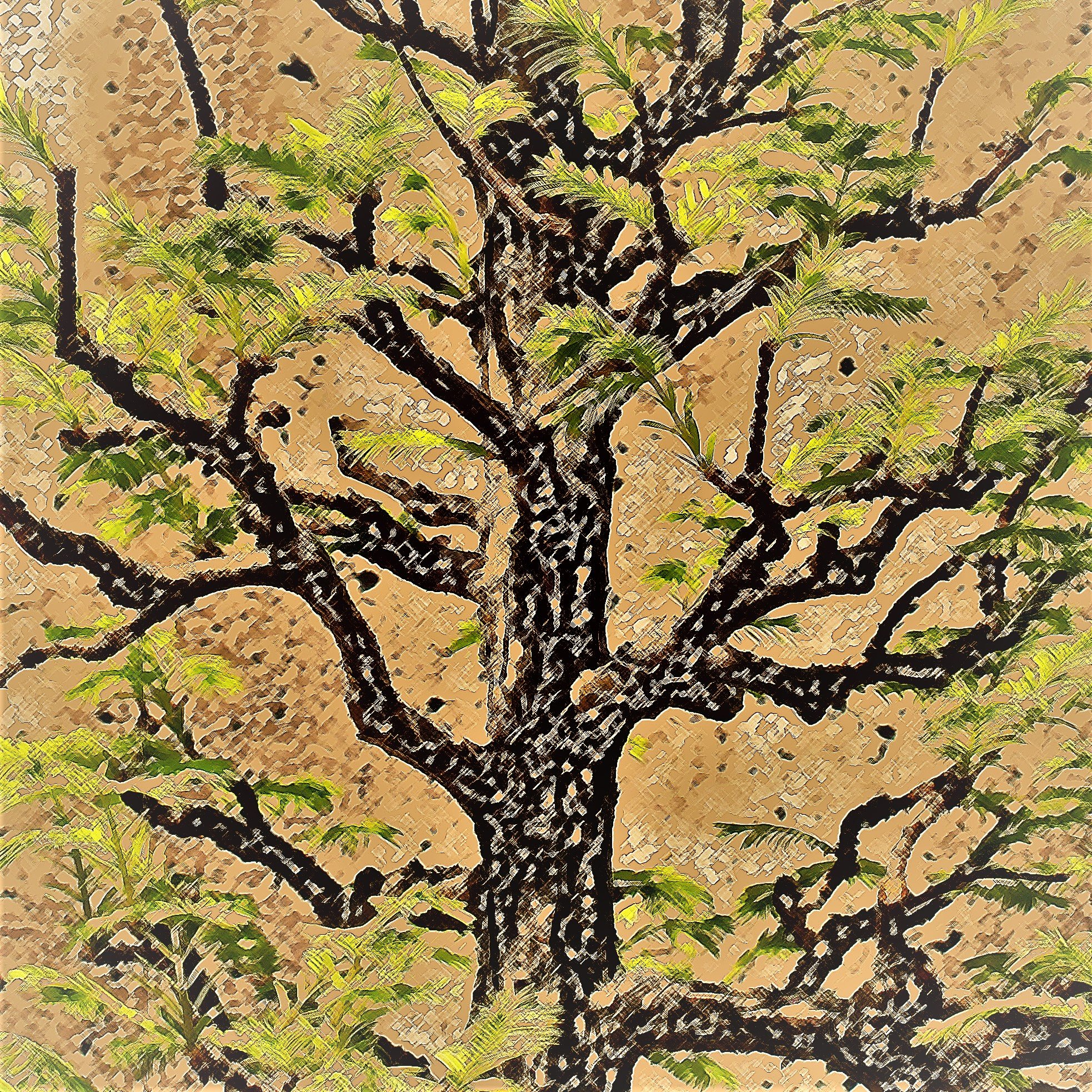

Naturalistic bonsai requires the study of trees in nature, with an eye toward truly seeing what trees do and understanding why they do it. That is the big attraction for me in coming to a place like Maymont. Here there are genuinely old trees of different species, growing out in the open where they can fully express themselves while being viewable from all angles, near and far.

We were new and there were many ideas about what The North Carolina Arboretum should be, and these were coming in all the time from various corners of special interest. The Arboretum wouldn't be able to satisfy all of them and we were apparently not in a rush to fully commit to any of them.

The North Carolina Arboretum’s bonsai enterprise began with a donation of little trees in 1992. Visitors, when they hear this story, often ask how many of those original trees remain in the collection. As usual when a question arises regarding numbers, I’m obliged to truthfully respond that I don’t know.

On the surface of it, there’s not much connecting crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) beyond the fact that both are woody plant species. Crapemyrtle is a deciduous tree originally from southern parts of Asia and Australia, while Scots pine is a coniferous evergreen native to mostly northern Europe. The two subjects of this entry, however, share several points of commonality.

Nature is where we began. As an element within nature, humans were one species among many, one link in the food chain, sometimes the eaters and sometimes the eaten.

Every choice the grower makes has some effect. Good design depends on good choices, and choices have a better chance of being good if they are done with thoughtful, well-informed intention.

No eyes, ears or mouth, no face, no arms or legs, no hands or feet — plants have no body parts that are recognizably the same as ours. Plants don't look like us. They don't act like us and we can't communicate with them.

Once we identify with something we tend to personalize it. Once we personalize something we grant it status as a unique entity, one of many, but separate and worthy of its own recognition in the greater scheme of life.

In the bonsai world, shows happen all the time. That highly reactive interface between human beings, with their individual natures, and little designed trees, each with its own character, can be found at any bonsai show. Our show is different, though. Most bonsai shows last for a few days or maybe a week at the most, while the show in the Arboretum's bonsai garden runs for more than half a year.

It was not until almost thirty years later that I identified that tree, from memory. So clear was my recollection of time spent up in that tree's boughs that I could distinctly recall the look of its bark, the shape of its leaves, the form of its structure. Once I started working at the Arboretum and learned something about plant science, these memories were enough for me to know the tree's botanical identity.

The bonsai garden is a premier attraction for the Arboretum, so having that attraction back online after a five month winter hiatus is a big deal. For me, World Bonsai Day is a deadline that can’t be missed. All those wonderful little trees and landscapes don’t get dressed up and lined out on the display benches by themselves — it’s a lot of work!

Visitors to the Expo were encouraged to vote for their favorite bonsai and in 2013 John’s baldcypress won hands down. Small wonder — the specimen is big and obviously old, and to see such a tree growing in a container defies belief for the average person.

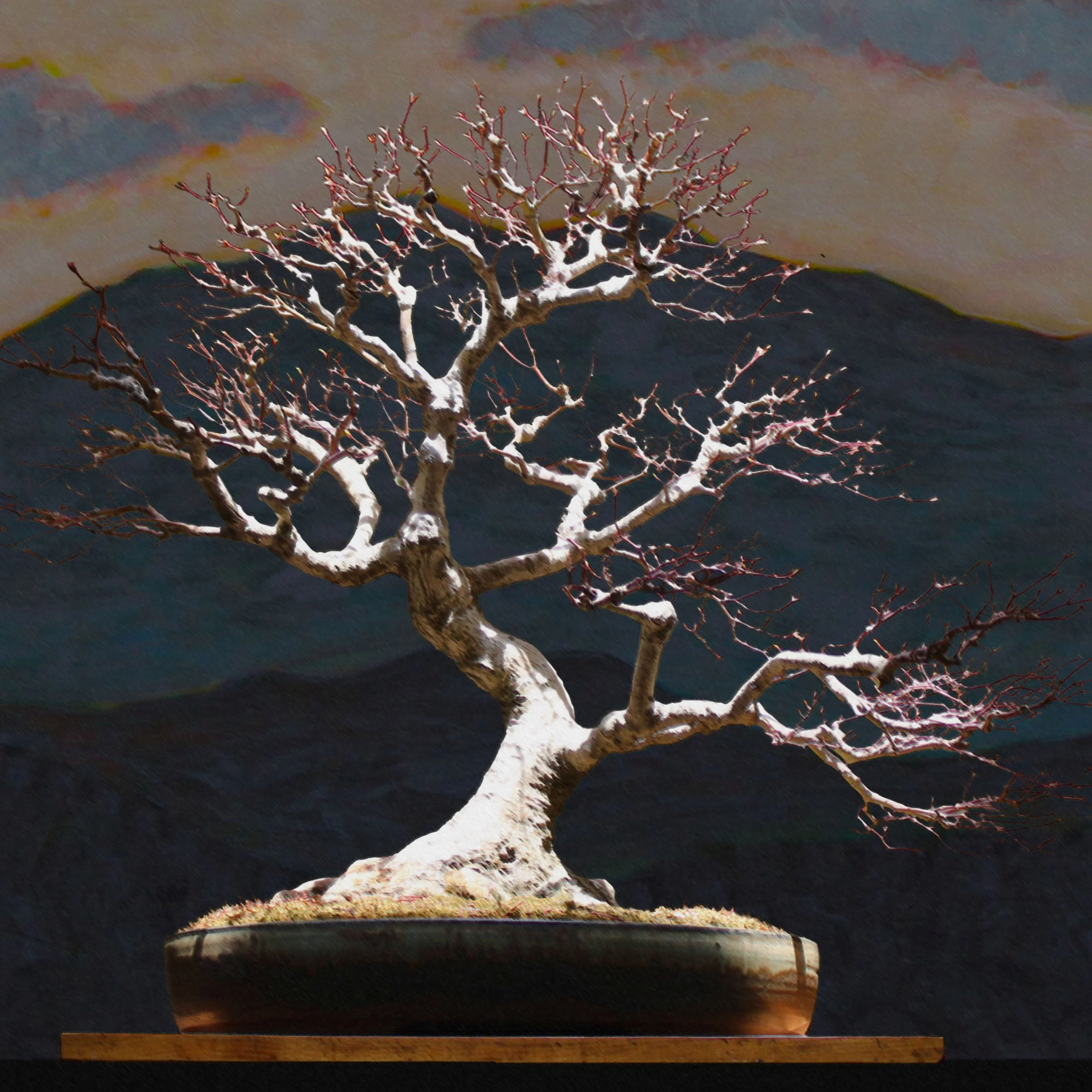

Foliage is wonderful, of course, but on a deciduous species the foliage is absent half the year. In the landscape, a naked Japanese cutleaf maple can still be beautiful for its form, particularly in the display of its branching and finely articulated twigs. The same can be true of a Japanese cutleaf maple bonsai when seen without its leaves. It can be true, but is not automatically so.

Mr. Martin had a diverse collection with some older looking specimens, and seemed to like his little trees to be on the large side. Most amazingly, a substantial portion of Mr. Martin's bonsai, including some of the larger, older looking pieces, were trees he had grown himself from seed.

We were The North Carolina Arboretum in the Southern Appalachian region of the United States, engaged in the business of building our own identity, which would primarily reflect our own unique place in the world. The three gardens comprising the Arboretum's core area, opened to the public just a year earlier, all modeled this approach.

I knew a challenge when I heard one. I went home that night and stayed up late to write out a statement by hand, then went to work the next day and asked my friend Cindy to type it up for me. Then I made sure the Executive Director and everyone else in administration received a copy.

Of the six or seven trees Kent had rounded up for our consideration, the one at which he now pointed was easily the least impressive. It was another pine, a Japanese black pine by the looks of it, wildly overgrown and terribly leggy. I didn’t see anything to recommend it.

The routine so familiar you know it by heart,

a well worn path trod year after year

yet remaining somehow eternally new.

Year Three

It must have looked suspicious. Picture a rest stop off an Interstate, a van parked by itself a little removed from any other vehicles. Two men stand outside the van, waiting expectantly, looking down the road and one of them now and then checks his watch. Finally a second van pulls up, right alongside the first.

What follows is an account of the late winter preparatory work done on a trident maple (Acer buergerianum) in a developmental phase. This same specimen has twice before been featured in the Curator’s Journal. The tree is revisited in this entry, on the cusp of its fourth growing season of bonsai development.

Banyan is a catch-all phrase for several different species of figs (Ficus sp.) that share the trait of producing what are known as prop roots from their trunks and branches. Emerging like threads from the tree's bark, these roots are pulled downwards by gravity until they come in contact with the ground.

When something goes bad or doesn't work right, blaming it on politics is always a safe bet. People think politics are inherently bad. Politicians are generally reviled and dismissed as being among the lowest of untrustworthy creatures, so much so that calling someone a "politician" is a slur.

The year 2005 was a watershed for bonsai at The North Carolina Arboretum. That was the year the Bonsai Exhibition Garden first opened to the public, in October on Expo weekend, and the advent of that space for displaying our collection forever changed the institutional status of bonsai.

The early years of the Carolina Bonsai Expo were an exhilarating experience. The show grew bigger and better with each passing year, with more people coming to see it and more clubs wanting to join. The undeniable success and popularity of the Expo became a prime driver of bonsai’s ascension up the Arboretum’s institutional ladder.

By the time of the final Expo in 2019, the event had established itself as one of the leading bonsai shows in the United States and was internationally known. For many years the Expo was The North Carolina Arboretum’s single largest event of the year as measured by visitation. Starting out, however, the Carolina Bonsai Expo was a humble affair.

In 1995 the Arboretum hosted a visit from the popular American bonsai artist Chase Rosade. He had bunches of very young plants of differing species, and at the end of the class he had three Japanese stewartias (Stewartia pseudocamellia) that weren't utilized, so he gave them to the Arboretum.

It turned out that keeping this elm under control while giving it the freedom of growing in the ground was not practicably possible. When I cut it back in the spring the tree would simply explode with new growth, as if it would just as soon be a big bushy shrub if I wasn’t going to let it climb up to the sky.

People who get into bonsai in a big way typically go through a phase early on in which every woody plant they see is evaluated for its potential to be made into a bonsai. That is, they will look at any smaller sized tree or shrub in a pot or in the ground and imagine how it might literally be turned into a designed miniature tree.

After twenty minutes or so, Duane came to my office and stood silently in the doorway. I looked up at him. "I think you better come look at this," he said. I walked down the short hallway to the headhouse work area, and there was the landscape planting out of the pot and sitting on the table.

We talked easily enough. Mr. Yoshimura's new surroundings were newer, cleaner and less cluttered than his home in Briarcliff Manor had been, and it felt different encountering him there. One thing hadn't changed, though — he still spoke to me in riddles sometimes.

Nine thirty the next morning I was at the hotel and Mr. Yoshimura was not waiting in the lobby. I stopped at the front desk and asked the woman working there what room Mr. Yoshimura was in. She told me the number then asked if I wanted her to call his room and let him know I was there. "No," I said. "He's expecting me."

On a mostly forgotten day in February, 1995, the telephone in my office rang. When I picked it up I heard Mr. Yoshimura's voice on the other end of the line. It was a happy surprise to hear his voice, because we hadn't spoken since my study visit with him in early January.

We decided we’d get out to the Three Sisters Swamp together and set about making plans to do that. A trip to an unfamiliar swamp in a remote area is not something to be undertaken casually. The only access to the Three Sisters site is by boat, so with the aid of the Internet John found a guide who leads tours of the swamp and we got in touch with him.

Sometimes you have to get away. No matter how you spend your time on a regular basis, and it doesn’t matter if you truly enjoy what you do, sometimes you have to get away. This year having a vacation meant more than simply getting away from the work routine for a little while.

In this part of the world, to be out in the woods in autumn is to know something of the sublime. More than a mere colorful delight for the eyes, there is a spirit in autumn that reaches deep into memory to massage an aching place of melancholy acceptance. Autumn out in nature is like free therapy.

A grower needs to recognize a tree's nature and accept it. If it can't be accepted, then maybe that tree isn't the right one to work with. Many a bonsai has come to an ugly end because the person growing it was determined to make the poor tree conform to a preconceived design idea.

Short of taking the sackcloth and ashes route and resorting to a life of humble debasement as penitence for having lived with eyes closed while whistling a happy tune in the face of the brutal randomness of our existence, there's little for it but to gather ourselves up and get back to business as usual, best we can.

From that low beginning, an entity seeking to recover must first endure and summon the will to go on. It must suffer the defeat but fight back, and persist in the struggle for however long it takes. Forever after, such an entity bears the stamp of the ordeal, for better or worse.

The heavy rain continued the rest of the afternoon, then all through the evening and all through the night without letting up. Somewhere in the darkness, as most people slept, the wind got up and started moving around, making itself known with murderous force. When morning came the damage that had occurred overnight gradually revealed itself.

Last night you read how the hurricane would land on the Gulf coast of Florida, then travel north-northwest through Georgia and South Carolina before arriving in western North Carolina. There would be lots of rain, the forecast said, maybe as much as twenty inches. There would be high winds too.

It amazed me that people were so generous. Their only motivation, so far as I could see, was to be helpful. They were supporting a new arboretum that was trying to start a new public bonsai collection, and if anything they had could be of use in that effort, they were happy to give it to us.

I had to actively advocate for bonsai's place within the Arboretum. Bonsai was still in the institutional position of being a curious side venture, an experimental anomaly, and nothing like a full-fledged program in its own right. I was no curator then. I was allowed to refer to myself as the bonsai caretaker for public relations purposes, but that was an unofficial title.

I sensed I had been maneuvered into a situation that had been carefully pre-arranged by Kent. I didn't mind it so much because he had made clear what was possible and what wasn’t, and he had done it so smoothly, with such good cheer and affability. I turned attention to the trees he was offering.

The bonsai professional had been taking the Englishwoman and her husband on a tour of the professional's bonsai garden. The professional introduced the curator to his English guests, explaining to the guests that the curator was in charge of a public bonsai collection in the United States and had come to Japan to study.

Those pots were made in Japan or China and their character was part of the whole “Ancient Art of Bonsai” package. In the beginning this was not a problem. The desirability of producing bonsai that adhered to a certain conventionally approved form was only another of the rules in a game I was learning to play. After some time, however, an unanticipated dilemma arose.

Containerization of plants is a remarkable phenomenon that few people ever think about because it's been done forever and the practice is so widespread and common. The discovery that a plant might be taken out of its natural context, introduced to an artificial environment and kept alive and thriving over a prolonged period was revolutionary.

We parked and got out of the truck, spending some time out in the chill and wind-driven rain, under the leaden sky, getting soaked while walking a beach all strewn with massive old trunks of driftwood dead trees. These giants were scattered here and there like matchsticks, the moving of them child’s play to the powerful currents of the strait.

After being greeted by the bear there in the dark early hours of the morning, I crawled off to bed. A few minutes later, or so it seemed, there was daylight streaming through the window. Then there was a bang on the door and it flew open and there was Dan, dressed and ready for the new day. In a booming voice he called out "You going to sleep all day?"

I was dead-tired as we stumbled through the night to the door of the house. I could not see so well but somehow sensed the house was of unusual construction, as Dan got out his key and opened the door. He stepped in and I followed. My head was lowered, making sure of my step in the dark through the unfamiliar threshold, and Dan said, "Say hello to Charlie!"

The call has come on many occasions. Someone has a bonsai collection that's become too much to handle, and now the trees need a new home. Our entire bonsai enterprise at the Arboretum began with just such a call, when the Staples family reached out to us about their mother's collection. The situation that prompts the call is almost always sad because it signals the end of someone's bonsai journey.

A fact that hadn't been so obvious before gradually became more evident to me while revisiting the history of this tree. Our Chinese quince bonsai seems to have served me as a personal gateway to naturalism. Naturalism in this context refers to a bonsai style, just as classical, neoclassical and modern are also bonsai styles.

The big "Y" shape formed by the sharply shifting angle of the trunk in combination with the strong right angle first branch was still in the middle of the composition, looking as awkward as ever. I wanted to address that now, but short of removing that big branch what could be done?

Such a state of full resolution is never achieved in bonsai. Because of the living nature of the medium, creative work with any individual bonsai is ongoing for the duration of the bonsai’s existence. The fact that the bonsai is alive dictates that it will change. Life entails growth and decline, and both are expressed in transformation.

I raised the tree from a seedling, birthed it as a bonsai, gave it its form, worked with it for nearly three decades and have always been fond of it. It was on display in the bonsai garden for many years and was even an Expo poster child. Yet somehow I've never been satisfied with this bonsai and have always struggled to work through my issues with it.

I'm a solitary sort of person, strongly inclined towards quiet introspection, with an unfortunate tendency to be cranky in social situations. I might be tempted to say I'd like my job even more if all it involved was working with the plants, were it not for a certain mysterious phenomenon that occurs on a regular basis.

It takes a little imagination for a water feature like Mountain Spring to mentally transport a viewer to some other, more natural watering hole in the forest. But even if the viewer has no imagination, they can still appreciate just the sight and sound of water cascading over the face of a big, craggy rock and into a pool. That experience is elemental and accessible. It's another matter altogether when the water feature is conceptual — that is, when the water feature doesn't actually have any water in it.

This little feature works familiar bonsai territory — the suggestion, in simple strokes, of something greater, calling upon the imagination of the viewer to make the connection. In the mind's eye of the visitor standing at the railing, the little splash of water may bring them back to the seclusion of a forest retreat.

Redcedar is not a favored bonsai subject, I think mostly because it is difficult to find suitable old trees with which to work. Trying to grow a redcedar bonsai from young material is a long term, long shot project. All four of the redcedar bonsai in our collection were donated to us, so they all had some age on them before we started working on them.

On the eve of construction, before the bulldozer came to work over the site in preparation for building the garden, I dug up one of the scraggly young serviceberries and put it in a pot. The little two-trunked tree didn't look like much. Collecting it was an impulsive act, done in the spirit of saving some living piece of what used to be, knowing that the space was about to be transformed.

The time leading up to the big weekend is a strange mix. There's stress because there's demand and a deadline, and the closer the deadline gets the more stress there is. The deadline is a worry, but that which must be done by the deadline is very enjoyable and really shouldn't be rushed, and therein lies the problem. All the high-value, creative pruning work an avid pruner could wish for comes due all at once, with a deadline.

The little red maple trees in the tray landscapes grew and presented a set of options with the multitude of parts they produced. In shaping them I relied entirely on the cut-and-grow method, using no training wire. With a pair of scissors I went about imagining life stories for the landscape trees, making choices as to what parts were lost and what path the canopy branches followed in their unending quest for sunlight.

Three Asian species — Japanese maple (Acer palmatum), trident maple (Acer buergerianum) and Amur maple (Acer ginnala) — are all considered excellent for bonsai use. Why not red maple, which is abundantly available in Western North Carolina? The answers I heard from bonsai people I asked were so emphatically negative I became leery of even asking.

The experience is suggestive, not limited by any need for what the viewer is looking at to be literally "old." The plants are shaped to look like they are old, to mimic the effects of age, done in a way convincing enough that the illusion prompts a response similar to what people would experience if they were in the presence of full-sized old trees of great character. Bonsai art, like all other art, works on our minds at the crossroads of memory and imagination.

The incredible character of these naturally miniaturized specimens lies somewhere at the heart of the bonsai impulse. Nature has always produced such trees in environmental extremes all over the world. Humans have always found something in the nature of these trees that speaks to us, compelling us to a more philosophic state of mind. They inspire us.

Year Two

The tree looked more convincingly decrepit but still grew strongly in its branching and foliage. The container made of chestnut wood also became more picturesquely weathered as it aged. For a few years everything was right about this planting and it attained that golden stage of development when the illusion of timelessness seemed permanent. Then the bubble burst.

There is a sense of timelessness inherent in a finely crafted bonsai. When the viewer stands before such a piece, there is the illusion of a moment suspended, an impression of all that came before and all that is to come obscured as if under enchantment. It is as if the bonsai came into existence just as it is and will always remain just so.

Gardens are beautiful because there is beauty in life. There is more than that, though. It is the inescapable fact of existence as we know it, that where there is life there must inevitably be death. Life feeds on death, on all levels from the microscopic to the largest manifestations of creative energy.

It is impossible to know what the future might hold for young and undeveloped talent. When I was young and collected baseball cards, the card manufacturers treated rookie baseball players the same way for the same reason. "Rookie" cards combined two unknown young players on one card. Usually, neither of the players would amount to much.

My guess is that very few of the many people who have admired "Yoshimura Island" over the past three decades have taken note of the ingenious composition. In truth, I did not fully appreciate it myself until I learned more about bonsai than I knew at the time the planting was created. What Mr. Yoshimura had done with the arrangement of this planting and why he did it was something I discovered only after years of looking at it and thinking about it.

Even today I can't think of a great many technical tips I can say for certain came to me from Mr. Yoshimura. He contributed a good deal of information in that regard, but it all gets blended in with things I learned elsewhere, before and after my time with him. The real gold of my Yoshimura experience was in all the stuff that perplexed me at the time.

I had brought along three ceramic tray containers — low-profile, good quality Japanese stoneware ovals, the kind traditionally used for forest plantings. Mr. Yoshimura looked at those a moment, then said, "Come with me!" At this he became animated to a surprising degree, scurrying in short, rapid steps toward the greenhouse. I followed.

When Mr. Yoshimura wasn't preparing me for the future, he was looking back over the decades of his own past, trying, I think, to discern why things went the way they did. He spoke of episodes from all different phases of his life, from the distant days of his youth up to the most recent years.

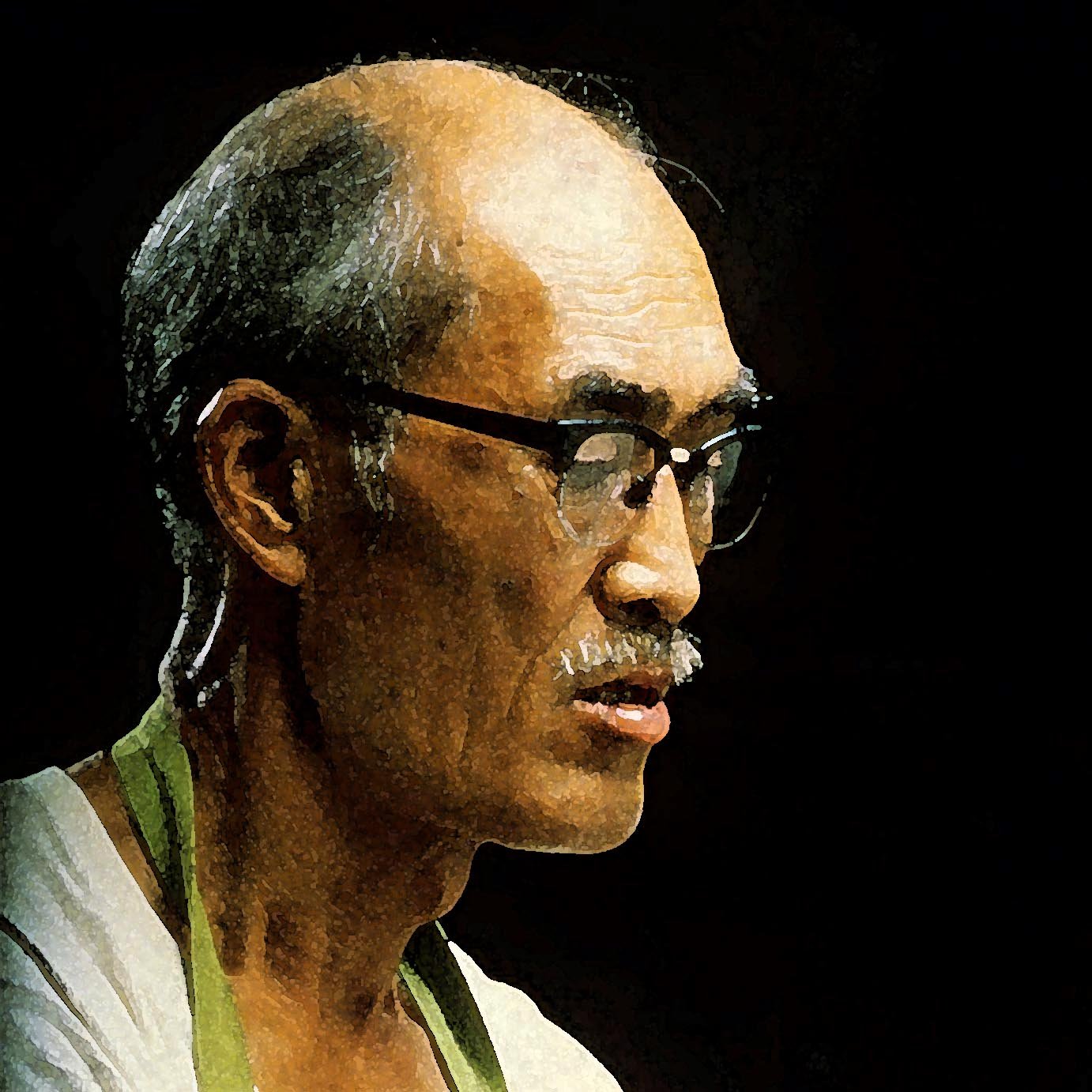

Mr. Yoshimura's teaching style was direct. He spoke declaratively and took pains to be exact in his statements. He expressed himself with authority that arose from an absolute command of his subject, acquired over an entire lifetime spent immersed in the art of miniature trees and landscapes.

Mr. Yoshimura loaded my slides into the projector's carousel then started projecting the images onto a small screen, also crammed into the room. Here my lessons began. As each tree's image was thrown up on the screen, Mr. Yoshimura would study it briefly and then begin a critique.

In January of 1995 I traveled to Briarcliff Manor, New York, for a three-day study session with Mr. Yuji Yoshimura. Shortly after my return, I wrote an account of the experience and submitted it to Arboretum administration to communicate the value of what I had learned. What follows is an unedited transcript of that report.

In writing about my experience with Mr. Yoshimura, I am looking back over a span of nearly thirty years— long enough ago that some significant changes have occurred in how we live everyday life. Perhaps greatest among them is the revolution wrought by advances in electronic communication.

As the new year began in 1959, thirty-seven-year-old Yuji Yoshimura began teaching bonsai classes at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. He'd arrived in America laden with all the bonsai materials needed because they would not be otherwise available. This amounted to more than a ton of baggage, and the whole operation must have required prodigious planning and organization.

The time has come for me to talk about Yuji Yoshimura. His name has appeared repeatedly in this Journal, because his influence on me — and, through me, on the Arboretum's bonsai identity — has been profound. But I have not yet told the story of the experiences with him that set my bonsai thinking on such a fateful course.

Once Don designated the bougainvillea as being excess plant material — not worth the trouble — it became valuable to me. I was not trying to prove anything or setting out on a mission to save it, but once the bougainvillea was deemed unworthy that meant nothing I might do to it would mess it up. I could try to make a good bonsai out of the wild bougainvillea just for practice, and if it didn't work out the plant could still go to the compost pile.

Those little trees earn their keep at this time of year by providing a leafy green bonsai presence in the Baker greenhouse from December until the middle of May. People appreciate seeing the tropical bonsai looking so vibrantly alive while the temperate world outside, wrapped up in the somber cloak of dormancy, settles into the relative dullness of cold winter.

Although the growing season is now over for temperate plants in our part of the world, there is at this time a flurry of important work that must be done. The last two months of the year see a reordering of business all across the bonsai front.

Let us take one last walk through the garden, down

The path we have strolled so many times before

In earlier days made golden by the alchemy of time.

The beech trees used in this planting were grown from seed at the Arboretum in 1993 as part of the landscape nursery operation. When California bonsai artist Ben Oki visited us in 1996 we gave him some of these very young trees and asked him to make a group arrangement of them.

It might be supposed by people who don't know the backstory that this specimen was given the poetic name The Ogre in reference to the gnarly features of the deadwood, which can be read as a monstrous creature with one small, beady eye glaring out. But really it was named for the person who collected, styled and donated the little tree to our collection: Nick Lenz, the original wild man of American bonsai.

Who does not feel something stir within them when they look upon the sight of autumn color in the landscape? What accounts for the melancholy we often feel, contemplating the changing landscape under a gray and cloudy sky, with the smell of wood smoke and a quiet chill carried on the breeze? Why does the past sometimes feel so close in autumn?

To say the herbaceous plantings are accessories or accents or even filler can seem a little dismissive. They have their own merits and can be appreciated for what they are. If we think of bonsai as being a miniature, living expression of the human experience of nature, why should herbaceous plantings not be included? Are they bonsai? The answer to that question depends on whom you ask.

A natural tendency toward obstinacy was only one factor in my inability to let go of the maple and put the sorry tale down to experience. While I was fumbling around with all the difficulties caused by the bifurcated root structure, I was having much more success shaping the upper portion of the tree. This maple was one of my earliest efforts at naturalistic styling and I was pleased with its progression.

An acquaintance back in the late 1990s gave me a little red maple (Acer rubrum) in a pint-size pot. It had been grown from a cutting taken from a tree that exhibited outstanding autumn color. Although this very young plant offered absolutely nothing to suggest it would make a good bonsai, I thought I would aim it that way because in those days every plant I came across was a likely candidate for that purpose.

There are times when the growing season feels never-ending, like the pruning and watering and close monitoring of the display trees and the garden landscape will go on forever. Nothing goes on forever, though. Summer is where the action is. Summer is alive and vibrant, demanding and exhausting. This was the thirty-first summer of bonsai at the Arboretum, the eighteenth summer in the bonsai garden. It was a good one, and now it's officially over.

Bonsai that are very big, or very small, or very old, tend to be the kind of bonsai that attract the most attention. It is their novelty that makes them so appealing. But the fact is that most bonsai do not fit into any of those three categories, and so it should come as no surprise that most of the bonsai in the Arboretum's collection don't fit into those categories either.

There was a lot of experimentation going on in those days. I tried many different techniques as a means of self-education, and some of these efforts succeeded while others failed. Starting new Amur maple bonsai from cuttings was a success. Starting a new Amur maple bonsai from a cut-back stump was a success. Putting these maples together as a group planting was also successful, although there was a hitch in the process that I didn't recognize until later.

Dana was a true lover of all sorts of plants, but especially bonsai. Even as she reduced her bonsai collection by sending much of it to the Arboretum, she was constantly acquiring new ones because she always had to have bonsai around to look at and tinker with. The trees she brought to my workshops for the club were always interesting subjects, whether for the type of plant or the age and development they exhibited.

In 1994, even as I was working toward the goal of a regional bonsai community with The North Carolina Arboretum at its center, I was trying to accelerate my personal bonsai learning curve. Word reached me early in the year that Yuji Yoshimura was going to be in Charlotte, doing a workshop program for the Bonsai Society of the Carolinas. Ever since meeting Mr. Yoshimura at the convention the year before I had been trying to figure out how to pursue the tantalizing offer of personalized instruction with him.

When the 1993 World Bonsai Convention in Orlando was over and I returned to work, there was so much to do. It was springtime and our fledgling bonsai collection was leafed out and growing, and now my imagination had been sparked by both the convention experience and the study period in DC before that. My mind was full of big ideas about improving the Arboretum's trees and all the work it was going to take to begin building a program to support them. But it was springtime in the nursery, too.

The idea of using a wooden planter for a tray landscape had somehow become appealing to me early on. The box used for the Graveyard Fields planting was a first attempt at such, and provided lessons that helped improve the wooden planters we subsequently built for use. After ten years in the wooden container, however, it seemed Graveyard Fields was ready for a modification to its look.

There is another Graveyard Fields. It is considerably smaller than the one off the Parkway but much more accessible, and it is never crowded there unless you want it to be in your imagination. The Graveyard Fields I'm talking about now is a miniature representation of the real place and it can be seen on just about any visit to the Arboretum's bonsai garden when little trees are on display.

When you look at an old bonsai you might never guess the history of it. For example, we have in the Arboretum's bonsai collection a large podocarpus (Podocarpus macrophyllus), which we can reasonably surmise to be around seventy years old. To look at it you might well recognize that it looks aged, however nothing in its appearance will give you reason to think our podocarpus grew up at a correctional facility. But it did.

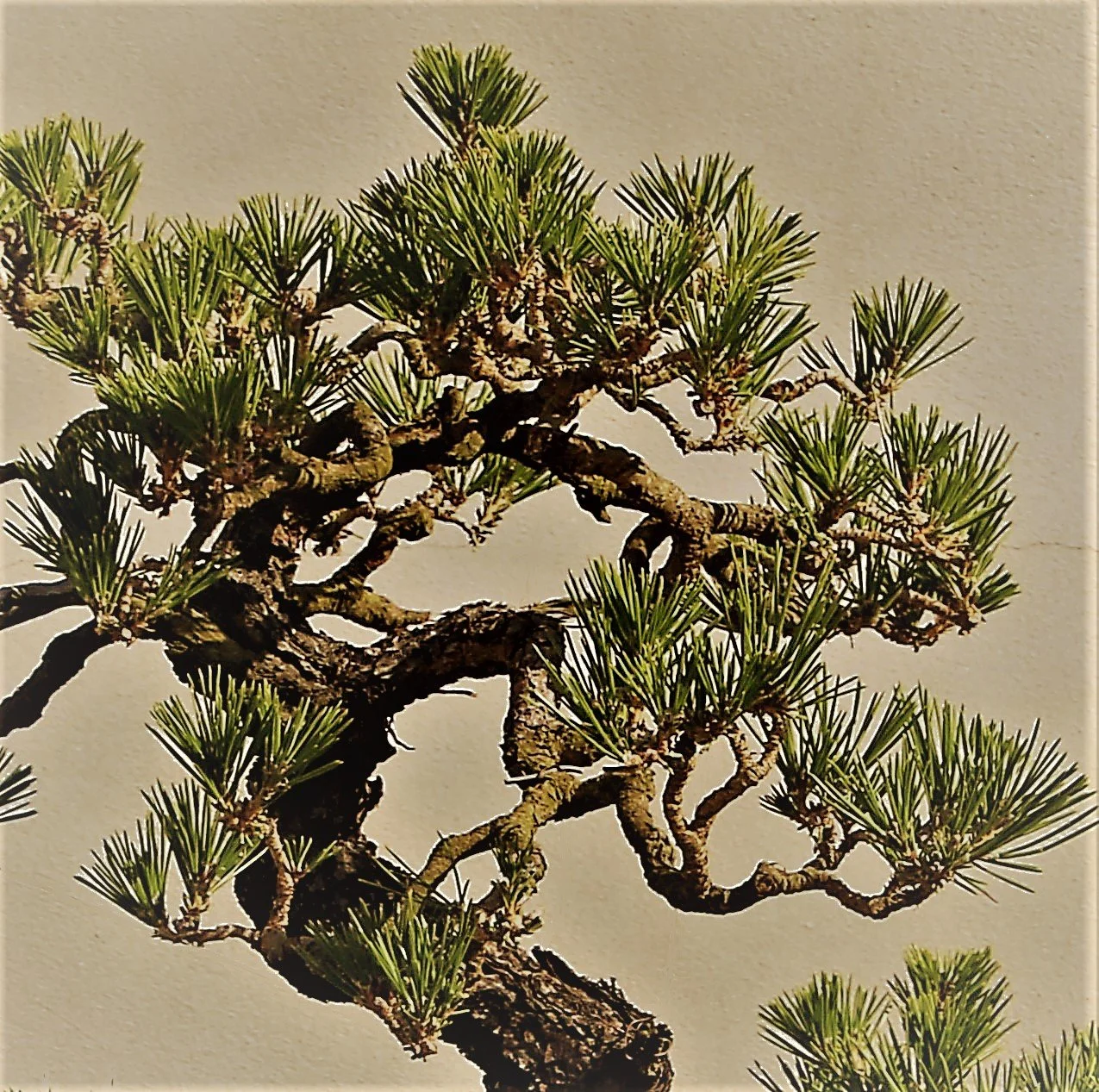

This small area is referred to as the Upper Level Entry Garden. It is very much part of the bonsai garden and it is maintained in the same manner. That means the Scots pine is pruned and shaped in a way that gives it an appearance suggestive of a bonsai.

No bonsai is created in a day. This particular maple has been years in the making and the session it goes through today is just another step along a path, another increment working off the increments that preceded it and setting up the increments that will follow.

There was a big pot made of redwood, the kind you might use for growing a tree out on a patio, and jutting up out of the soil in the pot was a piece of wood like an upside-down baseball bat. Mr. Staples came along so I asked him if the trunk in a pot was supposed to go with us. “Yeah,” he said, “That goes.” I bent to pick it up. “Be careful with that,” he said, “I paid five hundred dollars for that stick!”

In bonsai, American hornbeam is more commonly used than hop-hornbeam. The reason for this is somewhat mysterious, given both species work equally well for the purpose. This disparity is reflected in the Arboretum's bonsai collection, where we have numerous American hornbeam specimens but only one hop-hornbeam. The one hop-hornbeam specimen we have is substantial, however, and we've had it for a long time.

Most tray landscapes depict generic scenes from nature, but the possibility exists to have them represent more specific, real-life places. The challenge in doing this is finding a key feature of a given place that can be worked into the design of a tray landscape, suggesting the identity of the place being represented.

A person ought not walk on ice. Ice is slippery and hard, and although you might move across it carefully, thinking you are doing okay, suddenly your feet are flying out in front of you and gravity yanks you down from behind. When you hit the hard ice you get hurt. Best altogether to avoid walking on the stuff, if it is avoidable.

He didn't crack this like an obvious joke. He said it straight faced and then went about his business. This was one of several instances during the program where Mr. Yoshimura projected what I took to be an iconoclastic tendency. He was conservative in his appearance, precise and formal in manner, but seemed rebellious in his attitude. At the conclusion of the program I turned to Janet and said, "What a dangerous old man!"

Don was formulating a plan to have me further my education by studying with a well-known bonsai professional who was a friend and associate of his. When my horticultural mentor Dr. Creech caught wind of this he immediately stepped in and made arrangements for me to go to Washington DC to study with bonsai curator Bob Drechsler. Dr. Creech was insistent that this be done and he pulled all the strings to make it happen.

Even after removing the dead beech tree, I did not do much with the hemlock for a while. I spent the time taking care of other plants while keeping an eye on what remained of Mr. Yoshimura's tree and thinking about what to do next. I had always seen those trees as being subsidiary to some larger element: first the original primary trunk of the hemlock and later the American beech that replaced it. Now it was time to evaluate them on their own.

In the four years since the demonstration that brought them together, the beech and hemlock did well and both attained an agreeable degree of ramification in their branching. It is worth pointing out that even if a person is persnickety about larger sized leaves on deciduous bonsai trees, half the year there is no problem at all. American beech has distinctive leaf buds, too, so the winter look of this planting was particularly pleasing to me.

Faith is required, along with a bit of imagination, to see past the moment and focus on an outcome that is perhaps years away. That visionary aspect of bonsai design was another of Mr. Yoshimura's strengths. I should add that my decision to take a chance and try for something different, to be creative and innovative in my thinking, was also a product of Mr. Yoshimura's influence. Those were traits he stressed to me when I studied with him. I was paying attention.

Even without the little trees, the jewels at the heart of the garden’s identity, the place enchants. People slow down as they walk through, they speak more softly and look more carefully. The bonsai garden is not large but there is much to see in the layers of detail contained within. The second stage of spring in the bonsai garden begins on the second Saturday in May — World Bonsai Day — when the bonsai are returned to their benches and the garden is made whole.

The drive between Butner and Asheville took nearly five hours each way and the two journeys there and back were done as day trips, only a few days apart. We really had to pack the trucks to make everything fit in two trips, but amazingly we hauled everything without doing any damage. I had plenty of time on the long drive to think about how these desperate little trees would impact my life, but honestly, I don't remember what went through my mind.

Whatever their appearance and however they may be judged aesthetically, bonsai of this sort have the essence of some greater identity due to particular circumstances. This something extra may be a remarkable story involving the individual bonsai itself, or, as is the case with our dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), the added interest may pertain to the species of plant from which the bonsai is made.

This homegrown bonsai specimen stands out in autumn with foliage the color of a fire truck, a feature attributable to the tree's genetic inheritance as a red maple. It is large, standing just under thirty-inches in height, with a diameter of eight-inches just above the surface roots. That is big for a bonsai but small for a mature red maple, a consequence of the environmental impact of being cultivated as a bonsai.

In the case of this dwarf white pine, I decided it was not worth undoing what had been accomplished because I could not think of a better tree to make out of what already existed. If this bonsai were a maple or hornbeam, it could be pruned back hard to nothing much more than a trunk and a new design could be constructed from the resulting regrowth. Pines are different.

When the Arboretum accepted the unsolicited donation of a bonsai collection and I was offered the job of caring for the little trees, I tried to turn down the assignment. I was happy doing what I was doing at the time, which was most often manual labor out on the Arboretum property. We were outside most of the time, working on our own with more than four hundred wooded acres to keep us busy, and we rarely saw anyone else all day.

What do you want to be when you grow up? That is a standard question older people feel obliged to ask the young, or so it was when I was younger and I suspect the question is still out there. The older person who asks the question is only making conversation, trying to find out a little bit about you and what you are interested in.

The American hornbeam had previously been part of a different Arboretum landscape planting, but was removed because it had a more noticeably crooked trunk than the other trees with which it had been planted. The rejected hornbeam was in a storage area for several years when I noticed it and asked about its availability. The same crooked trunk that was previously seen as a flaw made the tree attractive for its new assignment.

Year One

The Curator’s Journal began publishing the last Friday in March, 2022. That means this week's entry brings us around full circle and we now officially close out the first year of the course. Here at the juncture where one year ends and another is about to begin, it seems opportune to pause a moment and take in the scenery, looking back at where we've been and surveying what might be ahead.

The idea of identifying what is most appealing about a tree and making that feature more prominent through presentation is elemental to good bonsai design. Other teachers have taught this, but I learned it that day from Mr. Yoshimura, on this juniper specimen.

It's the detail work, the non-glamorous, time-consuming, tediously repetitive labor done with tools like tweezers and a dental pick, that really elevates the quality of a bonsai and makes it shine. Virginia went about her business with a seriousness of purpose and unremitting focus that belied any suggestion the work was menial.

In 2018, eighteen years after being received in donation, I decided the time had come for this specimen to have its public debut and it was chosen to be the logo tree for the twenty-third Carolina Bonsai Expo. The unintended effect of the dangling branch revealed itself when I was making the Expo logo image. Suddenly what I saw before me took on a certain shape so clearly visible that once seen I couldn't un-see it. It was the image of a rearing horse.

Naming March in honor of a mythological being who embodied both growth and devastation is entirely appropriate. This month may see the first tender young sprouts of green life emerging from fertile soil, but it may also see those same sprouts freeze and turn into dark brown slime a few days later. March is fickle. What's behind the door — the lamb or the lion?

Now, twenty-five years later and with the advantage of hindsight, there are certain elements of my Japan experience that I recognize as having had more importance than previously acknowledged. It is time to shine some light on these matters.

From Ryoanji we walk another fifteen or twenty minutes to Kinkakuji Temple, another truly outstanding site. The gardens are beautiful, but the real highlight is a golden temple, three stories high, sitting above a large pond that reflects the image. It's fantastic, dreamlike. I shoot a million pictures, but it's unlikely that I capture on film the shock of seeing such an amazingly wondrous thing for the first time.

Even after years of pouring through books and magazines studying countless pictures of the great aged bonsai from Japan, nothing could have prepared me for the marvel of standing before the living trees themselves. All of them were apparently in perfect health, meticulously groomed, planted in exquisite containers, and everything I saw looked old.

A certain ephemeral effect that occurs only once every year can often be observed in February, especially toward the end of the month and in lower elevations. It is a small thing, a quiet thing, a detail that has to be looked for if it is to be noticed. But it is a heartening thing, a promising thing, a reminder that life ebbs and flows and the flowing is soon to begin.

Plans are all very well and good; I have made a few myself. Once you get underway your plan may or may not hold up to unfolding events. Unanticipated complications often arise, and then you face a choice of whether to stick to the plan or go with the flow. I remember reading that General Custer had a plan at the Little Bighorn, and he insisted on sticking with it even when reports started coming in that events on the ground were going awry.

Remember the adage that goes: "As the twig is bent so the tree is inclined"? It's an old saying, originally penned by poet Alexander Pope in 1732, and in full goes this way: "'Tis education forms the common mind, Just as the twig is bent the tree's inclined."

American hornbeam lacks the gaudy gene. It is an admirable tree species with four seasons of visual interest, but its appeal is understated and its virtues are so soft spoken that they are easily overlooked. I can't say I took much notice of American hornbeam either, until bonsai gave me reason to focus on it.

January is wintertime, generally cold and sometimes bitterly so, but there is something fresh and clean in the crisp austerity of a cold January day. This is the heart of the dormant season for temperate plants, but it is by no means a dull or dead time of year.

I was traveling with my friend John Geanangel, and we decided we’d make the best of the situation as long as we were already out there, so we toured around some. Our original plans were centered on trees so we kept that as the theme of the road trip.

Bonsai can be a vehicle for staying consciously connected to the natural world. It is a discipline, for those who practice it as such, that broadens awareness of the greater workings of life by focusing attention on a small but living piece of nature.

The challenge with this pine was not only to give it a new, more dynamic design, but to deal with an excess of long, leggy branches. A good many branches were removed in the demonstration, and others were intentionally killed but left in place on the tree as deadwood. This was the fate of that problematic lowest branch, which had been chronically weak from being in a disadvantaged position. Lack of light will no longer be an issue for that branch!

Bev cared deeply about bonsai and he recognized a situation was developing at this new public garden in Asheville that could have a far-reaching positive effect on the course of bonsai development in his home state — and maybe beyond. With our bonsai program only beginning to take shape, there was no guarantee it would ever amount to anything. Bev did what he could to ensure its success.

December's toil sets the stage for all that must be done in the next few months to prepare for another year of beauty and abundance. During the growing season no effort is spared to keep the garden looking lovely, and during the dormant season the goal is just the same. It is a different sort of lovely than you might find in May or July, but those of us who appreciate living in a temperate zone find serenity in its structural simplicity.

The Arboretum's collection has quite a few nice little trees with big, impressive trunks, and many of them were produced right here. How was it done? In-ground growing is the answer. Over the past 25 years or so, I've been refining my technique for producing small trees with large trunks. The new video presented here demonstrates part of the process.

Without the benefit of enormous size to indicate great age, most people would not necessarily recognize an old tree. It is another matter altogether to believe a tree no taller than yourself, with a trunk diameter no greater than the size of your leg, might be several hundred years old or more. Yet these trees do exist. Their size may not announce their age, but close observation of their appearance can reveal them.

When I found a lone American elm growing in a small plastic pot among the excess plants in the Arboretum's nursery, it had immediate appeal. The idea of making a bonsai out of a species so well known and badly troubled seemed a novelty, and at the very least it gave me the opportunity to protect this one individual tree. Though nothing about that particular elm, little more than a stick in a pot, suggested it would in any way make a good bonsai.

The telling of this particular tree's story should make one point plainly clear: It takes time to build a bonsai. Woody plants, even vigorous growers like American elms, develop at a rate most people find rather slow. On top of that the ability level of the person attempting to do the training of the plant has to be taken into account, and then come the hazards of chance along the way. Many plants are aimed for a bonsai future, but few actually make it.

November is a busy month in the world of bonsai here at the Arboretum, and for us the activity still has everything to do with the impending arrival of winter. Bonsai are still on display in the garden at the start of the month and will remain so until sometime near the month's end. Then the benches will be cleared off and the bonsai put into their winter quarters.

Being in nature is a multi-sensory experience, with things to see, hear, smell, taste and touch. Out of this experience comes a feeling, and born of this feeling is the desire to communicate its meaning to others. It was for this very purpose that humans invented art, in all its varied forms. I think bonsai at its roots is an attempt by humans to express to other humans an experience of nature. That must have been how it began.

Perhaps the most compelling physical feature of old trees is irregularity. Old trees are often crooked, bent, twisted, lumpy, asymmetrical and missing parts. These characteristics are the results of struggles with an unending variety of challenges faced by the individual tree over the course of a long lifetime.

It bears noting that the best way to know the age of any tree is to count its annual growth rings. If a tree has been cut down this task is relatively easy. On living trees a core sample can be taken using a tool called an increment borer, and the rings can be counted in the wood collected in the sample. This is not so easy to do and involves drilling a hole into the living tree. A good starting point is to look at a certifiably old tree and study its characteristics.

As a grower of ornamental plants, I welcome October. Right now, a good many of the plants I grow look worn out, their leaves spotted and dull. Soon, though, they will look briefly spectacular, ablaze in an array of seasonal color: purplish red into orange and rust, pale yellow into mustard and gold. Ours is a diverse bonsai collection that abounds in deciduous species and we can put on a great show in October.

All old trees have struggled to some extent, because life is as full of hazard and difficulty for trees as it is for people, and the longer one sticks around the more it wears on that individual, and the more that individual wears the effects of it. Time takes its toll. The little everyday struggles of life add up.

Although our trees are much beloved by the visitors who come to see them, they are nonetheless scrutinized and critically evaluated every day, because they are being shown. They are indeed presented as art objects, but they grow right where they are displayed and are not divorced from their natural context. The work done to enhance their aesthetic appeal can never be in conflict with their horticultural needs.

I forgot that I was looking at little Chinese elms growing in a shallow container and instead imagined them to be big buckeyes and yellow birches growing among the boulders on a windblown ridgeline. The tray landscape looked that believable to me. This seems implausible even as I write it.

Along with an appreciation of the virtues of native plant material came a growing appreciation of the native landscape in which those plants originated. And in contemplating the natural native example, ideas about the cultivated landscape began to change. Now you can also find more naturalistic gardens featuring plants native to the region where the garden exists.

For those of us in the bonsai game, September brings relief in two critical areas of concern: watering needs and rampant plant growth. Through the heat and glare of summer nearly every bonsai needed water nearly every day that it didn't rain; as we move into September there will be days when just a few plants here and there need "touching up" and there will be time to do a little catching up.

This humble but durable little tree has a poetic name: Golden Heart. It can be said, and not inaccurately, that this poetic name refers to the beautiful golden yellow color the tamarack turns every autumn. A quietly glorious sight to see. This bonsai is called Golden Heart for another reason, though, and it is something few people know about.

How did age get to be such a big part of people's general conception of bonsai? There are bonsai trees that are authentically hundreds of years old, and that sort of information makes an impression. People are fascinated by longevity, particularly if the age is beyond that which any person might expect to attain in a lifetime.

Trees are and always have been a subject of heightened awareness for me, and so I notice them. I notice them every day wherever I happen to be, and the notice is automatic, not necessarily conscious. I think about trees a lot, too, but often when I’m looking at them my response has more to do with feelings than words, emotion rather than intellect.

Despite the heat the plants are still growing. Some bonsai have already been pruned half a dozen or more times this year, but they are still growing and will need to be pruned again. Grow and cut and grow and cut and grow and cut. We practice what can be thought of as "pruning from the outside." That is, we are focused on appearances.

In Creating a Tray Landscape, the latest in our five-part docuseries, Arthur again takes a landscape from inspiration to completion. He creates a new planting featuring a lone weathered hornbeam and woody shrubs assembled with sculptural rocks on a natural stone slab. It makes for a scene evocative of the craggy Southern Appalachian highlands.

Aunt Martha's Magic Garden was put together in a public demonstration. Twice. The first time was in spring of 2008. We had received the donation of the hinoki bonsai in early 2006, so there had been two years to get to know it, to look at it and think about it. I had decided the best way to utilize the tree was as the centerpiece of a tray landscape.

It’s often our tendency when faced with a plant that looks unhealthy to reflexively think, What can I spray on it? One of the greatest dangers inherent in the use of chemical pesticides is that they are relatively cheap and easily available to anyone, regardless of the competence, intelligence or sanity of the buyer. These are dangerous and often lethal substances that can be purchased in quantity at the nearest big-box hardware store.

One truth learned by being observant and studying the ways of nature is that some parts of it line up with human desires and interests and some don't, and this is particularly true as regards farming and gardening. Those living beings in nature that facilitate the human impulse to cultivate plants we refer to as "garden beneficials." Those that work against our objectives we refer to as "garden pests."

It all starts with the energy of the sun and in July the energy is free flowing and the sun is beating down hot. The beginning of July finds us in the middle of the calendar year, and smack dab in the middle of the great cycle of life. July also finds those of us who care for the Arboretum's bonsai and bonsai garden out working in the sun, dealing with the on-the-ground reality of summer.

After the exhausting verbosity of the black pine articles, readers of this Journal will perhaps be relieved to find there are relatively few words to read in this latest entry. There is, however, a video to watch, and in it the verbosity will come to you in a different format. The “River of Dreams” planting is a favorite among those who visit the bonsai garden any time it is on display, and even more so if it happens to be flowering at the time.

What matters more, and the reason for detailing the history of this specimen, is the degree to which it has evolved. More than simply the product of normal aging, this particular black pine transformed the way it did because the person who grew it over the course of that time experienced an evolution of aesthetic sensibility.

Dissatisfaction was once again creeping in. The tree looked better to me now than it did when it was trying to be classical, that's for sure, but there was still much room for improvement….It was time to push the tree further along the path of design development.

If April is the time of horticultural anxiety and May is when the big green wave hits, June finds us engaged on all fronts, managing best as possible to stay atop a situation where life is surging in every square inch of the natural world. The plants are growing with greater energy than at any other time of year.

It took a long time to build that bonsai. To change it would require some drastic alterations that would likely set the tree back a decade or so. Whenever considering such a move you have to question if the end result would warrant the effort. Every tree has a certain limited capacity for perfection.

The bonsai garden is once again in a state of completion. It can be so only when the little trees are out on display and the public is there to experience them in the context of that special place created just for their enjoyment. The garden is not whole until the bonsai are in it. Just as the Arboretum, wonderful as it is, is more wonderful still when the bonsai garden is whole.

Trees, like human beings and all the rest of organic life, are not only subject to stress but are actually shaped by it. Think of a tree limb. A big, powerful, undulating tree limb is the product of a life of stress — the stress of reaching out to hold its leaves in position to access sunlight, and to hold them that way despite their weight and the weight of the limb itself against the force of gravity.

There is a process at work here: Every year in spring the tree is cut back hard, then allowed to grow unrestrained for a year. Out of the new growth some new possibility might present itself, or some previous idea could be undone by what happens in the course of a year of unrestrained growth. Flexibility is necessary; the tree has some say in what it will ultimately look like.

May begins with an array of colors in the landscape that is at least the equal of the celebrated colors of autumn. There is a certain color that, for reasons of marketing products like paint, is called "spring green.” But spring green is an amalgamation of just about every shade of green there is, from the dark richness of a spruce tree to the ghostly paleness of a fern’s unfurling fiddlehead.

When I think back on that time in Washington so long ago the memory is golden to me, an experience that positively changed my life. Connections made there that April led to other important learning experiences in the years to come, eventually taking me all the way to the other side of the world and back again.

It is possible, even likely, that the person who creates a particular piece of self expression, such as a bonsai, intends it to be perceived a certain way, to tell a certain story, but other people interpret it differently. There is nothing at all wrong with this. Ideas spark other ideas, and diversity is the catalyst in the evolutionary process that pushes all creation forward.

The Arboretum's collection has quite a few nice little trees with big, impressive trunks, and many of them were produced right here. How was it done? In-ground growing is the answer. Over the past 25 years or so, I've been refining my technique for producing small trees with large trunks. The new video presented here demonstrates part of the process.

In my experience, April is a natural time for beginnings. I was born in April, in 1957, met my wife in April of 1978, and began my career at The North Carolina Arboretum in April of 1990. As regards horticulture, in this part of the world April is when the growing season is undeniably underway.

My mind conjures up an image of all the tiny buds on all the little branches slowly swelling, then breaking, bursting open, pushing forth new growth all at once. Then that new growth begins extending, fresh green leaves unfurling, shoots stretching out everywhere in a riot of unleashed life.

Most folks don’t know Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana). One reason for this is that the tree has a very restricted range, naturally occurring only in some scattered parts of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Carolina hemlock is sometimes found in cultivated landscapes, but only rarely, and few nurseries offer it for sale.