What You Need

The man was strolling through the garden, taking his time, looking closely. He was by himself. I came along pulling a hose, watering the little trees. The man looked at me and recognized me as someone who worked there. "So," he said, "what's the trick with these things?"

"The trick?" I said.

"Yeah," he said, "what's the trick to making a bonsai?"

"There's not really any trick involved," I said. "If a person wants to do bonsai it comes down to having what you need."

"Well, what do you need?"

"First of all, you need a plant to work with. It may be a tree or a shrub or even a vine sometimes, but it has to be a plant that doesn't mind growing in a container and doesn't mind being pruned. Then you have to know how to keep that plant alive — not everyone knows how to do that you know."

"Yeah? That's not it, though, is it? You need more than that."

"Right. You need a pot to put the plant in, and you need some kind of cutters to do the pruning. Sharp scissors with a good point to them are probably the most essential tool, but some kind of tool to handle heavier cutting is often helpful."

"That's it? I got a plant in a pot and something to prune it with and that makes it a bonsai? Sounds like you're leaving something out."

"Sure. You have to have an idea of what you want the plant to look like. You have a plant in a pot and you keep it alive and you have your cutters and you use them to remove parts of the plant to give it a shape you think looks good."

The man looked around at the little trees on display and chuckled. "Yeah," he said, "I think you're still leaving some stuff out. How do you know what looks good? How do you know what shape to give it?"

"You're right," I said. "You have to have some image in mind, some concept of what a little tree ought to look like. You can get that from books or videos, or you can take a class. We have classes here, you know. If you take the class you get the tree, the pot, the cutters and some instruction from someone who knows what they're doing. At the end of the class you've got yourself a bonsai."

"Will it be a bonsai like one of these you've got here?"

"No. The little tree you get out of taking the class will be small and simple, something easy that makes a good starting point."

"Yeah, so what does it take to get to something that looks like one of these bonsai? What do you need to do that?"

"Time. You need lots of time because woody plants grow slowly and keeping them in a pot and constantly removing parts from them slows them down even more. You come out of the class with a simple little tree and then you grow it on from there. Twenty, thirty years later, if you're lucky and your work is good you might end up with something that looks like one of these."

The man chuckled again. "Thirty years, huh? That's a long time! I don't even know if I'll still be around thirty years from now. You must have a lot of patience."

"Right," I said, "you need patience. You need something else, though, too. You need a willingness to stick with it and keep going, no matter what, no matter how many things go wrong. No matter how many setbacks you suffer, no matter how many disappointments and outright failures come your way, you need the willingness to take the punches and keep on going. If you can't take the punches, none of the rest of it matters."

"Things come off the rails sometimes, huh?"

"Yes, things come off the rails all the time. Sometimes you can get your project back on track, and sometimes not. Sometimes what you're working on comes off the rails and you get discouraged, then you pull yourself together and start laying down some new track. You get on that track and keep going. Maybe things go off the rails again, and then you repeat the process and keep going. You keep doing that until you get to someplace you think is right, or until you give up, or until the plant dies and then the game is over."

The man looked silently at the little trees for a few moments. "Well," he said, "I really like these bonsai, but I don't think I'm up for all that."

"That's okay," I said. "You can come see these trees any time you like and we'll take care of them for you. Thanks for being here today," I said, then went on with my watering.

Back in the early 1990s, when the Arboretum had a first-rate nursery operation, a visitor offered us some acorns. They were English oak (Quercus robur) acorns, and the man who offered them spoke with an English accent. He said the acorns had come from the Robin Hood Oak in Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire, England. Robin Hood Oak is an alternate name for a famous old tree that’s better known as The Major Oak. The tree is estimated to be upwards of one thousand years old and is, as many ancient trees are, hollow. The alternate name derives from a legend that Robin Hood and his men sometimes hid in the gigantic old tree. There was no way to know if the stranger was telling the truth about the source of his acorns, but they were from an English oak and we didn’t have any of that species growing in the nursery. We accepted the gift and grew a number of little English oaks in little plastic pots. I don’t know what became of the others, but there was one of these trees still kicking around in a pot when we disbanded the nursery a few years later. I took that tree into the bonsai holdings and started working with it.

English oak leaves look very much like those of our native white oak (Quercus alba), only they are naturally smaller in size. That was an attraction. White oak is one of the great trees in this part of the world, and happens to be the most common tree species on the Arboretum property. I have tried numerous times over the years to make a white oak bonsai, but never with success. Like many of our native oaks, Quercus alba does not take well to bonsai culture. Quercus robur, on the other hand, had already proven amenable to container culture, and that, taken together with its smaller leaf size, suggested it might work as a bonsai subject. I figured it wouldn’t hurt to give it a try.

The first move was to take the tree out of the pot and plant it in the ground to accelerate trunk development. The specimen grew in the ground for about five years before I collected it and brought it to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in the early 2000s to use as a demonstration piece. I brought the oak to Pennsylvania bare-rooted, wrapped in a large plastic garbage bag. People in the audience were making bets about how long it would take to die. The little tree took the ordeal in stride, however, and resumed life as a containerized plant without complaint.

In 2007 we in eastern North America experienced what I have come to call the "False-start Spring." The first two months of the year were so mild that plants began to break dormancy in early March, and by the beginning of April even plants in the landscape were approximately one month ahead in their development from what they normally would have been. Then, during the first weekend of April, winter temperatures returned. The traditional frost free date for this region of the country is May 15th, so winter weather in early April is nothing unusual. Having little or no such cold weather in January or February is very unusual, however, and when even native plants in the forest mistakenly think spring has arrived and then are thrust back into winter, the result is disastrous. Many established trees in the landscape, especially Japanese Maples, were severely damaged that year. Plants in containers suffered even worse.

That spring I had to throw away a few trees because after a while these unfortunate specimens revealed themselves to be permanently dormant. There were numerous other trees that took their time growing a second crop of leaves to replace the earlier ones that were nipped in the bud by freezing, but I waited on them because the green under the skin of their branches told me they were still in the game. The English oak happened to be one of these plants.

I began to worry about it, though. All the other damaged plants one by one recovered and clothed themselves again in green, while the English oak sat there naked and forlorn. April passed, and May, and nothing happened. There was still green showing under the bark, however, so I continued to wait. June came and went. July came and went. August arrived, and still this one little tree was bare and seemingly without life, appearing even more so for all the other leafy plants prospering all around it. Still, it showed green when I scratched on its limbs. If this situation had gone on much longer, I may have killed the tree by stripping off all its bark while continuously checking to see if it was still alive. Toward the end of August tiny buds finally appeared. The tree eventually produced little leaves, maybe half their normal size, and just one sparse crop of them. The growing season for this oak that year was about six weeks, and then the leaves fell off. Next spring it came out normally. The tree lost some limbs, but after allowing it a year of vigorous growth I was able to begin working with it once more in 2009.

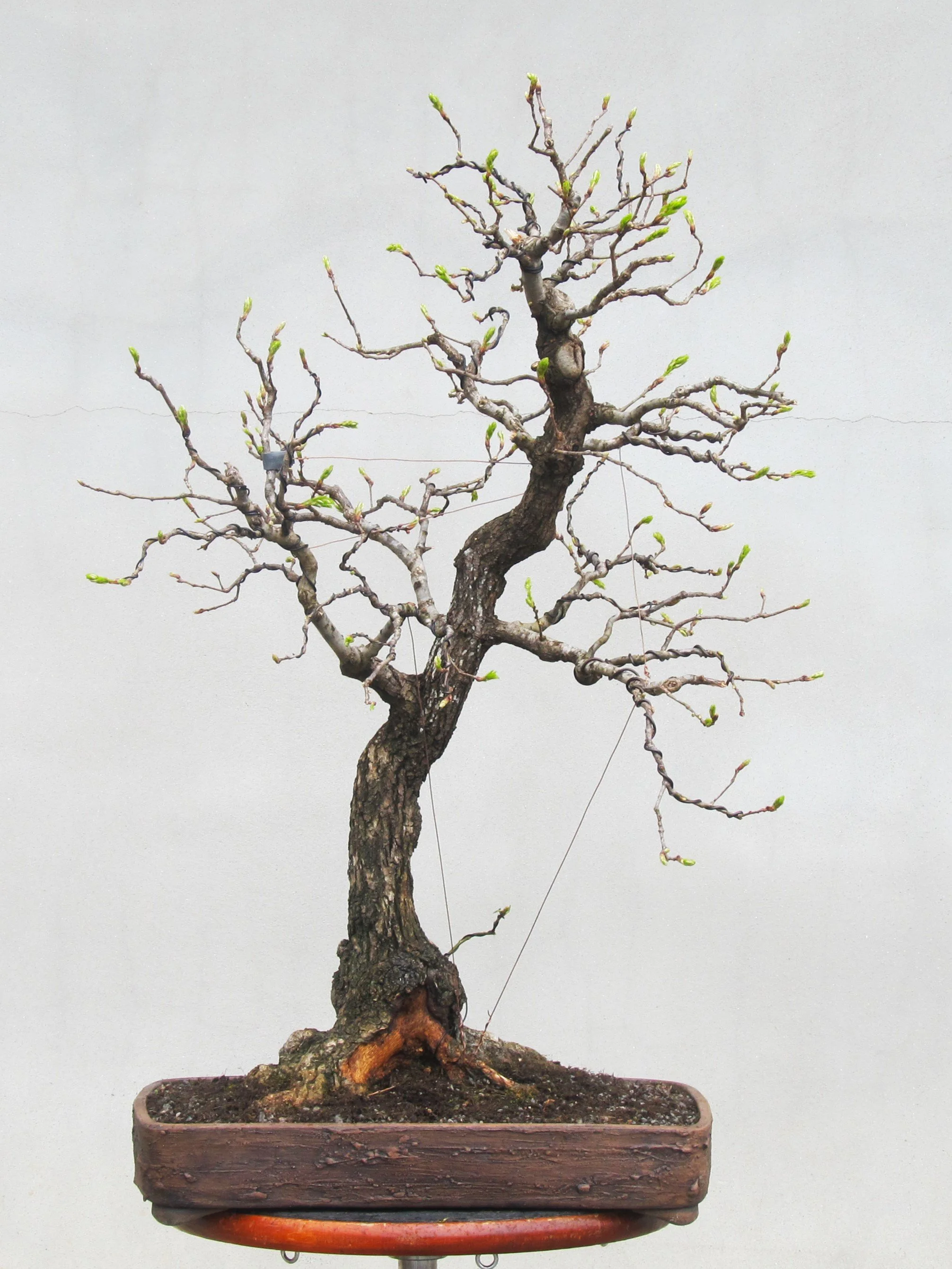

The first photographs I have of this tree are from that late winter styling session:

February 2009, before

February 2009, after

February 2009, before

February 2009, after

I also took a photo showing the range of leaf sizes on the tree:

Dan Chiplis, from the US National Bonsai and Penjing Museum, long ago told me that the smallest leaf you find on a tree gives you an indication of how small you might be able to make all of its leaves under proper bonsai culture. Over the years, I’ve found reason to think this true.

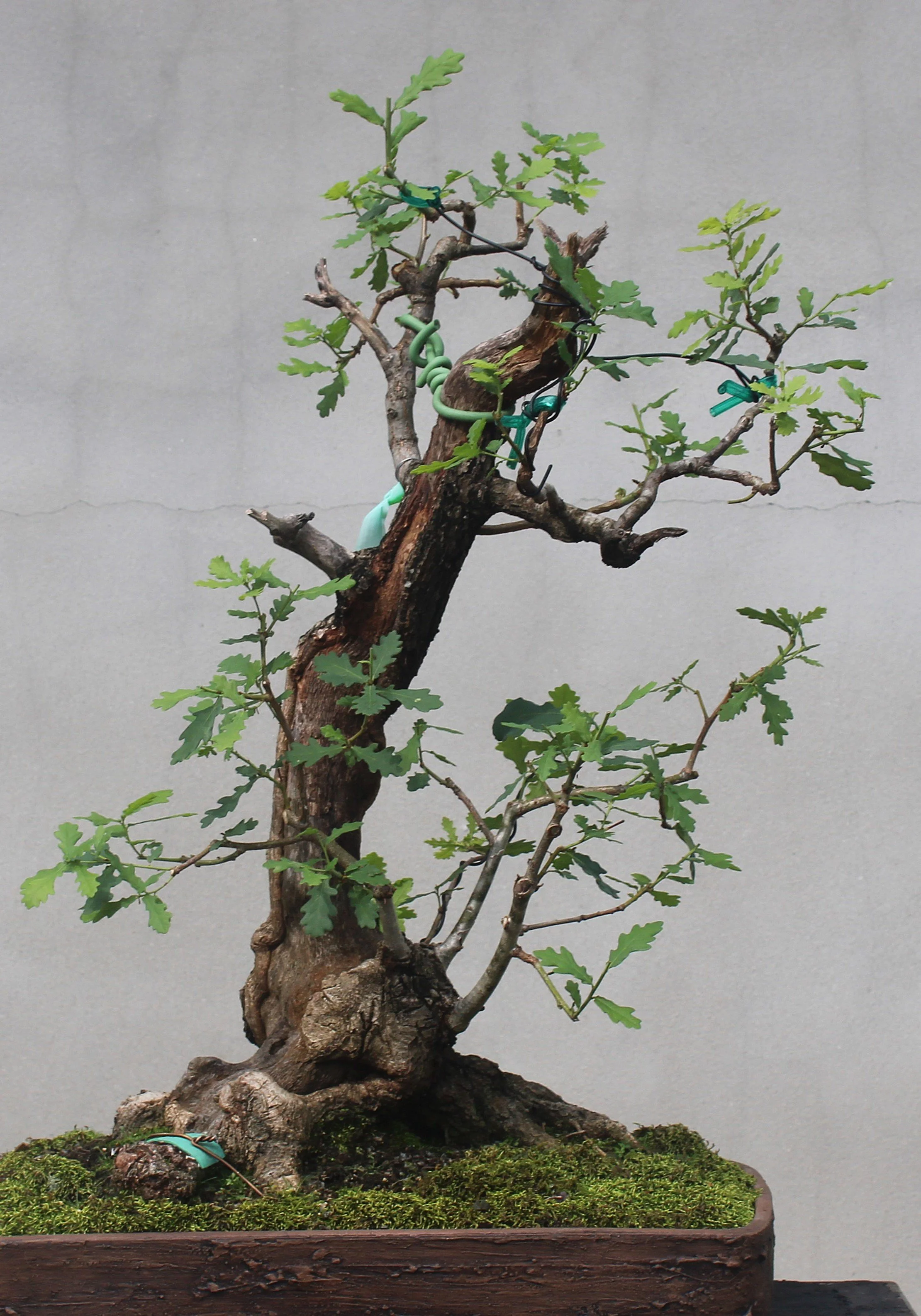

Two years after the above images were made, the English oak looked like this:

July 2011

October 2011

More branch ramification is evident in this image from the following year:

October 2012

At the end of 2012, the oak was given a thorough pruning and wiring to set it up for the following year’s growth. The photos I made then include the first to show this specimen from any perspective other than what I thought of as the primary viewing angle:

December 2012

December 2012

December 2012

The next set of images from 2013 show the oak going through seasonal change. They also document that the specimen made its bonsai garden debut that year:

April 2013

May 2013

June 2013

Photos from 2014 show an in-the-round view of the oak in autumn (its autumn color is usually underwhelming):

November 2014

November 2014

November 2014

November 2014

Something unfortunate happened to our English oak after that. I’m not certain exactly when, but one day I looked at the base of the tree and noticed an unusual texture to the bark in one place, a sort of bubbling up that made it look like something was pushing it up from underneath. Unfortunately, I recognize that look. I took a knife and began to poke at the bark in this zone, and it began to pop off. Everything beneath the bark in this area was dead. Here is how the tree looked in spring of 2017:

May 2017

This development was pretty discouraging. The oak had come a long way from its humble acorn beginnings and was finally starting to look like something. Die-back on trees is always associated with some event, often a wound, as might occur from an accident or a pruning cut. In this case I suspect the cause might have been fungal, although I never saw any evidence of it. Regardless, our English oak now had a big, fat dead area right front and center on its base when seen from the primary viewing angle. I considered trying to carve it out and make it into a cavity, but never followed through on that idea. Instead, I let the tree be and didn’t put it out on display that year.

The dead zone remained stable and over a year’s time weathered to a darker color, becoming less noticeable. I grew used to it, as well, and ultimately brought my mind around to accepting what had happened. I didn’t think the die-back enhanced the tree in any way, yet it didn’t ruin it, either. The next year I put the oak back out on display and no one seemed to mind that the tree now had a compromised base:

May 2018

July 2018

The oak was on display again the following year. In the picture below, note that a sprout emerged from alongside the die-back area and I elected to let it remain. Although I didn’t really have a plan for this sprout, it wasn’t hurting anything and I thought it might eventually develop into a useful feature:

May 2019

July 2019

By the time of the above images, I had come to think of the dead zone on the base of this tree as part of the oak’s character. I was comfortable with it, and felt comfortable letting the tree handle the matter, to go about doing what trees do when injury occurs to them. The dead wood continued to weather well, developing ever more interesting texture, and callous was building up all around the periphery of the wound. The wound area looked stable. I was good with it.

Then — one day I was working on the oak and looking at it closely, and noticed an unusual texture to the bark in an area extending upwards from the site of the die-back. The bark had that same bubbling up appearance. I took a knife and once more started to fleck off pieces of the bark that were no longer adhering to the wood below. The dead zone this time extended for several inches up the trunk line, front and center. Not long after, the lowest branch on the tree, which had always been robust, began to show signs of stress. Leaves turned yellow, then fell off until the branch was bare. Now the whole front of the trunk in the lower third of the tree was dead, and the number one branch was dead too. Game over.

I thought the game was over, but the tree didn’t. All the other parts of the oak were still good, still growing, still strong. That tree still wanted to live and I wasn’t going to be the one to tell it otherwise. I mean, I grew it from an acorn! This tree might be the offspring of one of the greatest oaks on earth and I had grown it from seed and nurtured it for more than twenty years, and I was proud of it. It was the only oak in our collection and it never failed to impress people that we had a bonsai oak tree. You don’t quit on a tree like that.

I took our English oak out of the nice Robert Wallace pot that had been its home for many years and planted it in an oversized mica container. The oak was placed in an out of the way spot in the hoop house and left alone. I’d notice it now and then when I was out there, and I’d stop a moment to look at it and think about it, always reaching the conclusion that the tree was hopeless now as a bonsai. Perhaps I should take it out to the woods and plant it, let it be a catch and release type of situation and maybe the battered little oak could still go on to have a good life.

I didn’t do that. Instead I let it go on growing in its big pot and the oak responded by pushing out vigorous growth from all the parts it had that weren’t dead. I’d trim those rank shoots now and then and I’d look at the tree and try to see something in it. Finally, just last year, I thought I saw something.

One October day I brought the English oak into the shop and started working on it again. You know, I never really liked the top of the tree — too clunky. This is my chance to do something about that. Let’s take that top off, leaving a stub behind as dead wood. Let’s run that dead zone right up to the now dead top of the tree. Let’s yank the uppermost living branch into a more upward position, so it can take over as a new top for the tree. Hey, that’s not so bad. Those multiple sprouts coming off the base of the tree, let’s choose some of them to keep, and then train them to start behaving like little trees of their own. Huh — look at that. I think we’re back in the game:

October 2024

October 2024

October 2024

October 2024

October 2024

With the current growing season reaching the point where at least some of the trees start slowing down, I took the opportunity the other day to spend a little more time on this sentimental favorite. It happened that this was a tough week for me personally, and as I worked on this tree I was relating to it. The tree has had some hard knocks and it shows. I suspect some people might say it has no future, yet there it is — hanging on and still growing. Maybe another disastrous event is looming just around the corner, and this one will put an end to it.

Maybe. Time will tell.

Meanwhile, still in the game:

July 2025

July 2025

July 2025

July 2025

Author’s note: The image at the top of this page is a re-worked version of a photograph titled “The Major Oak” that was originally made by Andrew Tallow.

Attribution: Wikimedia Commons