The Age Thing Again - Part 4

Early on in this series of entries I suggested that size is not dependably an indication of old age in a tree. Since then I have offered numerous examples to illustrate the characteristics of old trees and their various parts, and every one of these examples featured large specimens. The reason for this seeming discrepancy is that I organized the subject of diminutive old trees into its own category and put it aside for closer examination separately. The time has come to turn our attention to them.

First, though, a momentary detour into semantics: It has always rankled me to hear the term stunted used to describe bonsai trees. It is not because this descriptor is inaccurate, but rather that it carries a decidedly negative connotation. It is difficult to think of an instance when application of that word confers a compliment on whatever is being described. To say a thing is stunted is to imply that it has been frustrated in its attempt to be something else — something greater — and as a result it has been misshapen into a lesser form. If a tree has the capacity to grow seventy feet tall but is kept to a size a mere fraction of that, it must indeed be legitimate to describe that tree as stunted. But I don't like the sound of it. Another term one might use is dwarfed, which sounds a little less judgemental but still has generally negative associations. My own preference is for miniaturized. That word clearly conveys the idea that what is being considered is of smaller form than usual for its kind, but it does not suggest any deformity or inferiority. Perhaps that is because our society has undergone and continues to experience a revolution of miniaturization, brought on by technology and epitomized by the microchip. Stunting is mean, but miniaturization is cutting edge.

Sometimes in nature trees are miniaturized by their environment. That is to say, it is not genetics that makes these trees smaller than most others of their kind, but the conditions in which they grow. In our part of the world, miniaturized trees are most often associated with higher elevations. Weather conditions in the mountains are typically more severe than they are down in the valleys, with colder temperatures, stronger winds and a greater incidence of snow and ice. The growing season is shorter in the higher elevations and soils are often thin, composed more of mineral content with less organic matter.

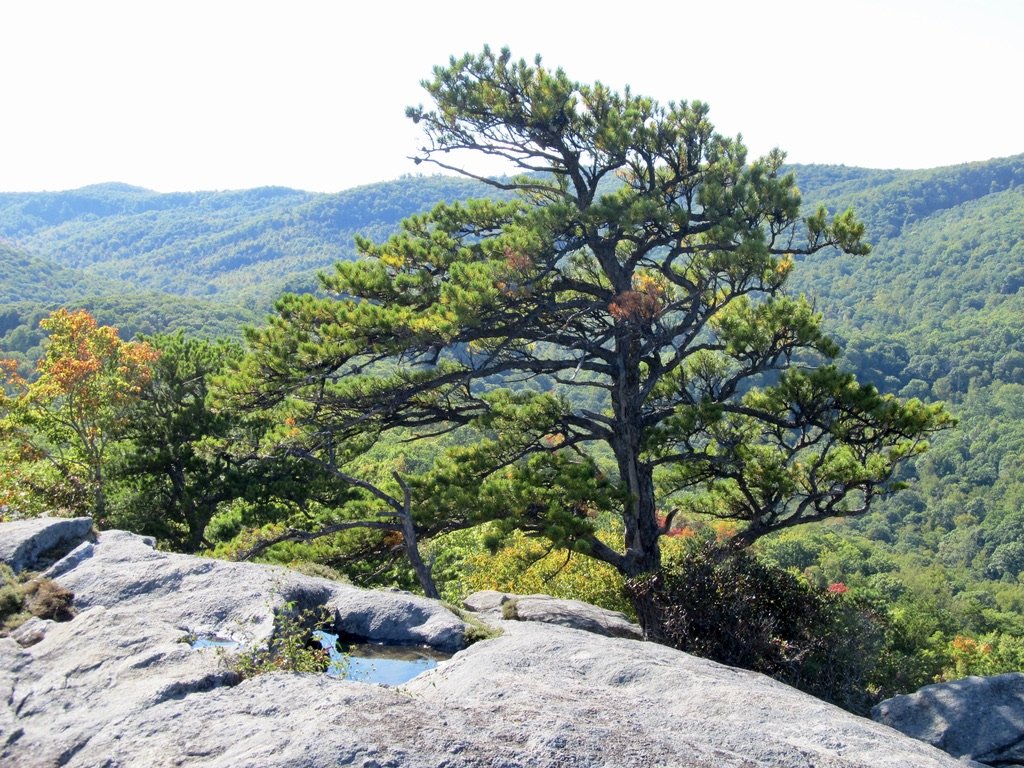

Imagine a windblown Virginia pine seed coming to rest on a tiny pocket of gravel and decayed organic material that has collected over the course of countless years, built up in a depression on an exposed rock outcrop high in the mountains. The seed manages to germinate and become a seedling, sending its roots down into the soil and pushing its stem up to the sky. The little pocket of soil can contain only so much moisture and offers little room for growth, so if the pine is to survive it must conserve water and be relentless in its quest for more root space. The young tree will seek out and exploit any opportunity to push roots outward into new territory, such as might be afforded by a crevice in the mountain rock where moisture collects and is protected from evaporation. A crack in otherwise solid rock might not seem to offer much hope for a tree, but every little bit of moisture is precious and roots are amazingly powerful in their efforts to access it. Life for the tree isn't any easier above the soil line, where natural circumstances suppress the pine's attempts to grow toward the sun. Harsh conditions limit the extension of stems and can cause repeated damage to foliage, limbs and trunk, so even if the tree is tough enough to survive it will not be able to carry on life processes in normal fashion. Its annual growth will be accumulated in small and tortured increments. After many decades, if the Virginia pine growing on the exposed rock outcrop survives, the tree might look like this:

Other environments can also result in miniaturized tree growth. Rugged coastal regions sometimes feature harsh conditions not unlike those found on mountaintops, with the added challenge of salt spray coming off the ocean.

Miniaturized oaks growing on the shore of Long Island Sound in Connecticut.

Inland there are places where the soil is sandy and poor, the sun is hot and rainfall limited, and here, too, woody plants struggle to live, attaining stature only slowly.

Miniaturized oaks growing in central South Carolina.

Pygmy pine forest in southern New Jersey.

Some perspective; these trees are not necessarily very old, but they are fully mature.

The attrition rate for woody plants attempting to make a living in these challenging environments must be even greater than in more ordinary places, where only a few individuals are able to attain old age. Those that survive long term under the life-threatening conditions of a harsh site can be awesome in their rugged character, or they might be just runty and broken down "trash trees," depending on who is doing the looking. One thing they won't be is large. Old trees growing in the harshest environmental conditions are always, to some degree or another, miniaturized, dwarfed or otherwise stunted.

Does their small size make them inferior to the larger of their kind? Are they lesser trees than those that have had the advantage of an easier life? An argument might be made to support either idea, but I won't be the one to make it.

To live a long time and become old is neither wholly good nor wholly bad. It is an accomplishment, though, because all living things have a limited lifespan and relatively few of any particular kind make to that span's farther reaches. How much more impressive it is, then, when longevity is achieved in the face of adversity. At the time of this writing I am sixty-five years of age, which in our culture is no longer considered very old. A few thousand years ago, a sixty-five-year-old person would have been considered uncommonly ancient and worthy of veneration just for making it that far. Now I would have to stick around another thirty years or so to reach the same degree of status. The difference can be found in the fact that life has become easier for human beings in our culture now as compared to how it was for people back then. Sixty-five years of striving against greater hardships and facing more constant danger makes for a greater accomplishment than sixty-five years of living in comparative comfort and security. Should not the same logic tell us that a one-hundred-year-old tree living in a harsh environment is even more worthy of veneration than a similarly aged tree living in a comfortable environment?

The problem is, without the benefit of enormous size to indicate great age most people would not necessarily recognize an old tree. It is easy to believe a gigantic tree that has a base so large it takes two or three adult people with their arms extended and fingertips touching to encircle it might be several hundred years old. It is another matter altogether to believe a tree no taller than yourself, with a trunk diameter no greater than the size of your leg, might be that old or more. Yet these trees do exist. Their size may not announce their age, but close observation of their appearance can reveal them. All the indicators of tree age previously discussed are applicable to miniaturized trees: the look of the bark, the irregularity of their shape, and the visual evidence that there has been a long history of damage and recovery. The challenge is to get to the places where these miniaturized trees grow and to see them for what they are.

If one word should be used to sum up the look of an old tree, and particularly in describing an old tree that has spent its life struggling to survive in a hostile environment, the best I can think of is character. It is the character of such trees that speaks to us. Their appearance tells us about the nature of life, and what it means to live and grow and come to terms with adversity, and to eventually become old and abide in the inevitability of death. The character of old trees tells us a primeval tale, the most compelling story there is.

For obvious reasons, naturally miniaturized trees have special appeal to me. My interest is never in the prospect of collecting them for bonsai use, but rather to be able to study them, marvel at their existence and photograph them if I can. They belong where they are. Not all of them are of a collectable size either. Some stand fifteen or twenty-feet tall, but that is only a fraction of the size they might attain if they were growing in more comfortable conditions. The following gallery features some of my favorite images of naturally miniaturized old trees in the mountains of Western North Carolina (click on image for full view):