A More Prosaic Account of the Present Season

Although the growing season is now over for temperate plants in our part of the world, there is at this time a flurry of important work that must be done. The last two months of the year see a reordering of business all across the bonsai front.

In the bonsai garden the change could hardly be more stark. Typically in November, usually around Thanksgiving time, all of the bonsai on display are removed to their overwintering quarters. The look of the empty benches is a sad prospect after enjoying the little trees in three seasons of leafy allure, and knowing that emptiness will continue for the next five months only makes it sadder. But it needs to be done. If it were possible to know in advance what the worst of the winter weather might bring and when it was going to happen, we could react accordingly and leave the trees on display until it was necessary to vacate them. Of course, no one can know such information beforehand with any assurance, regardless of what the most advanced computer models or the pages of the Farmer's Almanac might have to say about it. For that reason, at the end of November the displays in the garden get cleared out.

There are two locations in which temperate bonsai are stored for the winter, and one is the hoop house out in back of the production greenhouse. During the growing season the hoop house is covered in shade cloth, but for the dormant season it's covered with white polypropylene. Effecting that changeover is one of the more potentially adventuresome jobs of the year. Removing the shade cloth and rolling it up in advance of putting it in storage is not so difficult. Handling the big sheet of plastic — the poly is one hundred-feet long and forty-feet wide — is another matter. It comes tightly rolled on an eight-foot long tube and is unspooled the length of the house, and then by means of ropes attached along one edge the plastic is pulled over the metal hoops that form the support structure of the house. Once the plastic is successfully in place it must be fastened down along all its edges in a manner secure enough to withstand the windiest day or night that might occur in the next five months. The operation requires the coordinated physical efforts of four or five people, together with a bit of luck. Once the big sheet of plastic is unspooled, from the time it is being hoisted into place to the time it is finally secured in place, the slightest breath of breeze can wreak havoc. A gust of wind can spell disaster. Misfortune has shown its spiteful face occasionally in the past, but this year all went well with the house covering.

The other space for overwintering bonsai is the walk-in refrigerator in the basement of the bonsai garden pavilion. About thirty bonsai, including most of the largest and heaviest, spend in excess of five months stored in total darkness at thirty-five fahrenheit degrees. Some of the plants stored are coniferous evergreen species. The refrigerated trees are at a temperature that induces dormancy, precluding the possibility of green foliage photosynthesizing, so the evergreens do not need light any more than the bare deciduous do. The bonsai still need to be monitored for water needs. The cooling units in the refrigerator take moisture out the air like a home air conditioner does, so over time potting medium can dry out. The amount of watering necessary is minimal, however. Perhaps once every two weeks or so a few plants need to be rehydrated.

The idea for the walk-in refrigerator came from The Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts. They have the oldest public bonsai collection in the United States, started in the 1930s with a donation of specimens imported from Asia by an American diplomat. When The North Carolina Arboretum was planning its bonsai garden, we looked around at bonsai facilities at other public venues and found the Arnold Arboretum was overwintering their valuable bonsai in a refrigerated blockhouse. They still do. We learned from their successful example.

For the Arnold Arboretum it is a matter of protecting their little trees from too much harsh New England winter. Back then in the early 2000s they would put the collection into storage every year on Labor Day and take it out again on Memorial Day. For us the refrigerated storage unit is used mostly to address the vicissitudes of winter in our region. From one week to the next, from one day to the next, even from daytime to nighttime, the weather in our region can be all over the temperature map until around about the middle of May. Tree roots are adapted for life in the earth where the temperature is more stable and slow changing. The roots of trees in pots are subject to air temperature because they are contained in medium that is surrounded by air. Outside air temperature in Western North Carolina can shift more than forty degrees in less than twenty-four hours some days in winter, and that rate of fluctuation is unnatural for tree roots. The little trees we put in the refrigerator at the end of November will be subject to only constant cold, but never freezing, until they are brought out sometime in early May. In effect, it's the perfect winter. The plants go to sleep and they wake up again when we bring them out.

Because bonsai is such an integral part of The North Carolina Arboretum's identity, we always want to have at least some bonsai on display for visitors to enjoy. From December until early May there is a small display of tropical bonsai provided in the greenhouse at the Baker Exhibit Center. Sometimes in the summer we have a few tropical bonsai specimens scattered among the trees on display in the garden, but mostly we show them indoors in the winter. This year's winter bonsai display was installed just this week and will open to the public on Saturday. The seldom-seen tropical little trees will be waiting for you next time you visit.

The amount of work happening now, busy as it is, does not compare to the level of demand that exists from early spring on through the growing season. During that time period it is not advisable to take much time away from work because there is too much to be done. Once we reach the final months of the year it becomes more practicable to take off, and so I generally do. Twice this past November — once early in the month and again at the very end — I was away from work and on the road for reasons of personal recreation. Even on my own time, however, the subject of trees is always in mind.

In early November I stayed a few days at Edisto Beach in South Carolina. While there, an outing took me to a nearby natural area called Botany Bay Plantation Heritage Preserve. As the name indicates, this site was in long ago days a working plantation. Now it has been largely reclaimed by native flora and fauna, and is kept in a state of being mostly wild but with an access road and several parking lots. It's a great place to see a natural environment completely different from that which we have in the mountains.

Large, old Southern Live Oaks (Quercus virginiana) dominate the woodland landscape with their picturesque forms:

Appealing as is the coastal forest reclaiming the old plantation, the most distinctive part of the Botany Bay preserve is at the shore, where land and sea meet. In this case the sea is on the rise, actively reclaiming the land. What the visitor to this beach witnesses is the slow but surely active destruction of the forest by an elemental force. At the forest's edge are large old trees being undermined by waves at high tide. A short stroll toward the ocean brings you to a debris field consisting of the remains of large old trees that were probably still alive a decade ago. It is eerily fascinating to walk among these fallen skeletons and experience the form of trees from a whole different perspective, to see normally hidden parts revealed:

The reshaping of coastline all over the planet is a game the land and sea have played since a time long, long before any humans showed up to contemplate it. The situation may be exacerbated by the effects of climate change but the larger process at work predates that. It's a remarkable thing to see.

In late November I journeyed northward and found myself in Eastern Pennsylvania, which is a fine place to be, full of history and culture. Part of the trip brought me back for a return visit to the Morris Arboretum. The arboretum is on property that used to be the estate of a wealthy Victorian couple named Morris, who enjoyed traveling the world and collecting plants for their landscape. Many of the trees date to the early 1930s, but there are still a few originally planted by the Morrises back at the turn of the previous century. Many of the old specimen trees are Asian species:

American Beech (Fagus grandifolia)

Greek Fir (Abies cephalonica)

Japanese Zelcova (Zelcova serrata)

Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum)

Lacebark Pine (Pinus bungeana)

Katsura Tree (Cercidiphyllum japonicum) This tree is more than 120-years old.

Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostrobodies) This impressive grove of trees was planted in the early 1950s, making it comparable in age to those planted at The North Carolina Arboretum.

Dawn Redwood - These trees benefit from growing next to a stream.

Dawn Redwood - The tall, straight trunks throw dramatic shadows across the ground as the sun sits low in the sky.

Sometimes as I go about our Arboretum I look at trees we have planted in this landscape in the thirty-something years the Arboretum has been here and imagine how they might appear fifty or a hundred years from now. There is no telling which trees might live that long, but some will and people as yet unborn will enjoy them as great old specimens.

Another stop on the Pennsylvania trip was the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Great trees can be found both outside and inside the fine old Greek-revival building:

London Plane Trees (Platanus acerifolia) This grove is planted in a park alongside Benjamin Franklin Parkway, across from the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Weeping European Beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Pendula’ ) This is a nicely shaped older specimen planted in the landscape on one side of the museum.

Empress Tree (Paulownia tomentosa) This is not a particularly old tree, but it is developing well and situated in a prime location. It is in a courtyard alongside the great staircase leading to the main entry of the museum, where to this day you can see any number of visitors running up the steps and doing the Rocky dance when they reach the top.

Painting by Claude Monet

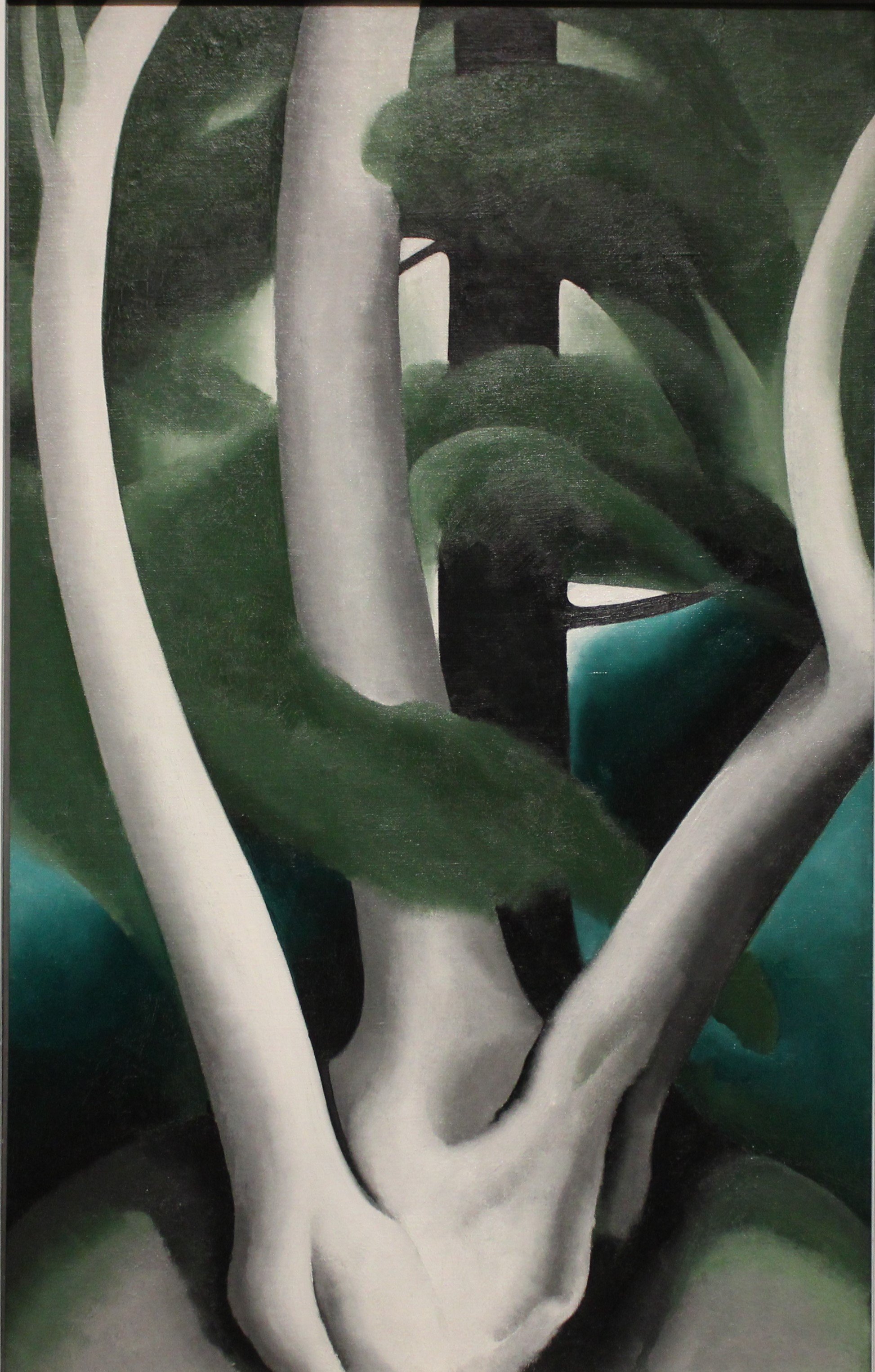

Painting by Georgia O’Keefe

Painting by Harold Weston