The Age Thing Again - Part 2

Before going any further, it bears noting that the best way to know the age of any tree is to count its annual growth rings. If a tree has been cut down this task is relatively easy. On living trees a core sample can be taken using a tool called an increment borer, and the rings can be counted in the wood collected in the sample. This is not so easy to do and involves drilling a hole into the living tree. There is also a mathematical formula for estimating a tree's age, using a predetermined growth factor number for the tree species in question multiplied by the diameter of the trunk at a height of 4.5 feet above the ground. I have never done this.

These techniques come at the problem from a certain direction and are attempts to answer the age question with a number. That with which we now concern ourselves pertains to appearances, and so our eyes must provide the information.

A good starting point is to look at a certifiably old tree and study its characteristics. As a case study, let's use this Osage orange (Maclura pomifera), growing at Red Hill, the Patrick Henry National Memorial in Virginia:

The age of this tree has been established by core sampling, and it is in excess of 350 years. It stands more than 60 feet in height and the spread of its crown is greater than that. It is the largest of its species known to exist.

Here is another view of it with a human alongside for a sense of scale, showing the tree to be a multiple trunk specimen:

Two views of the lower trunk and base of the tree:

It is difficult to tell in a photographic image that does not include a person standing nearby, but the base of this tree is massive. Although size is not always an accurate indicator of age, in this instance it is. If you are standing before this specimen the bulk of it gives a distinct impression of having been many years in the making. It is also helpful to have some prior knowledge of the tree species under consideration. If you are familiar with other Osage orange trees it will be recognizable that this particular one is substantially larger than what is typically encountered, suggesting greater age.

The base of the Osage orange tree also has the appearance of age though not in as pronounced a way as is often seen. The base is the point at which the lowest portion of the trunk emerges from the earth. Typically this part of the trunk is the greatest in circumference and features the presence of surface roots. Although some old trees do not have powerfully flaring bases and large and prominent surface roots, many do:

Swamp Chestnut Oak (Quercus michauxii)

American Elm (Ulmus americana)

Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides)

American Beech (Fagus grandifolia)

Live Oak (Quercus virginiana)

Red Spruce (Picea rubens)

Common Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Katsura Tree (Cercidiphyllum japonicum)

Baldcypress (Taxodium distichum)

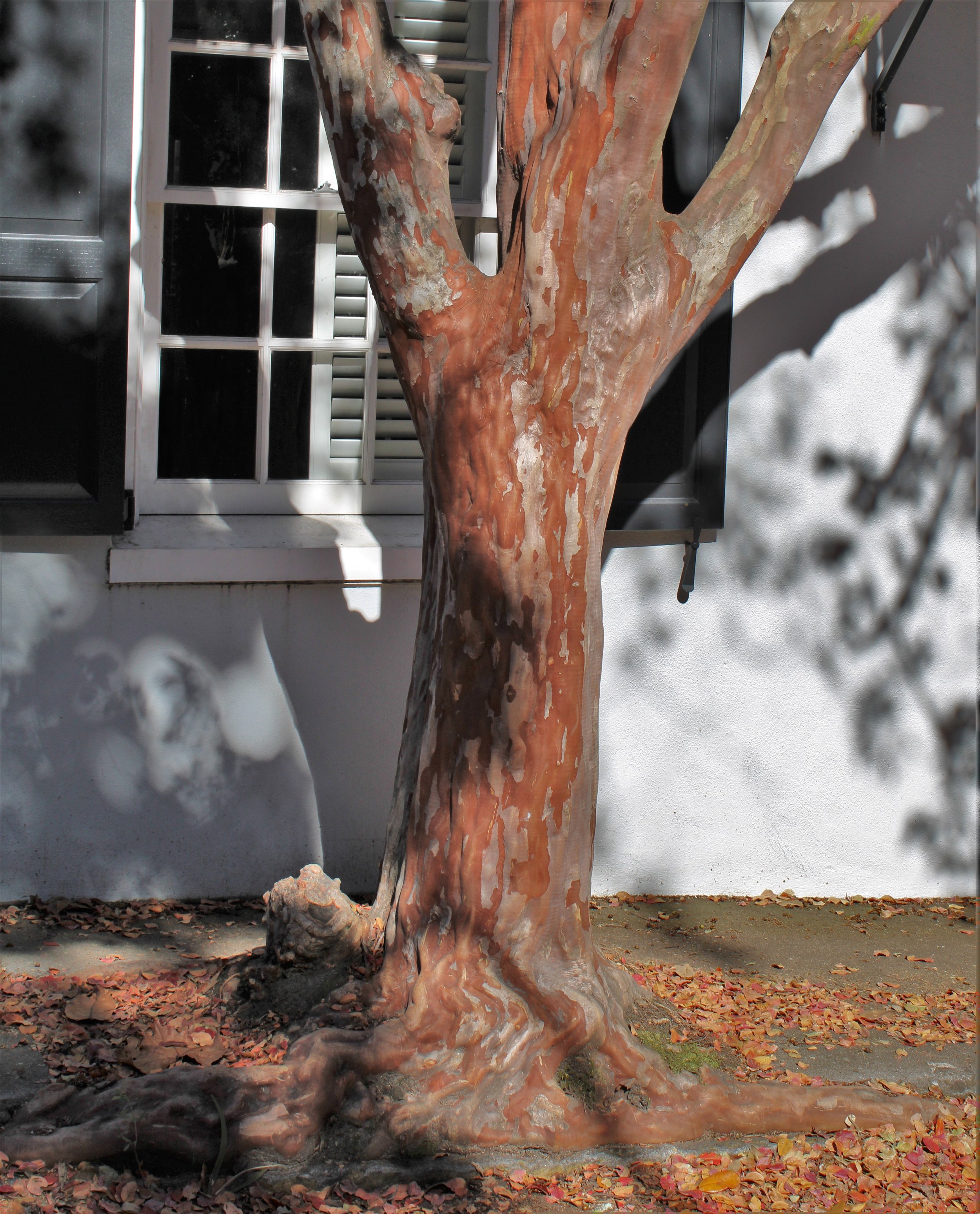

Another tree feature that can be indicative of age is the look of the bark. The Osage orange provides a good example:

The trunk of a tree is built of numerous layers, the outermost one being called the rhytidome. The rhytidome is composed of mostly dead cells produced as the tree grows by other layers under it. This is the trunk surface we see and what is typically thought of as the bark, although bark also consists of multiple different layers. Bark is built up slowly, thin layer by thin layer over the years. The older parts of the tree, mostly the trunk from ground level up to the lower branches, feature the thickest and most impressive accumulation of the rhytidome because it has been building up there for the longest time. In the oldest trees this outermost layer of bark usually has a distinctive appearance, richly detailed and complex, often with pronounced texture and high degree of tactility. It is difficult to describe the look of an old tree’s bark beyond that, but it is noticeably different.

Here is a sequence of three Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) images, depicting from left to right the changing nature of the bark as the tree matures (click on any image for a larger view):

In older trees, as the bark builds up, other trunk features may appear. This may be in the form of a characteristic mature growth habit in certain species, such as the muscular look of hornbeam or the fluted base of baldcypress, or it might be a collection of burls and other warty protuberances. These lumps and knobs seem to occur randomly and can be concentrated on some individuals. Old wounds can also affect the look of bark on an aged tree trunk.

Bark is interesting anyway, varying in look from species to species, but it gets more and more so as the tree ages. Here are some examples to illustrate the point (click on any image for a larger view):

To be continued…