Dana

A defining characteristic of the bonsai program at The North Carolina Arboretum is the generous support from a host of caring people that has accompanied every step of the journey. One such helpful individual passed away last week, prompting this remembrance.

Dana Markham was a longtime member of the Hinoki Bonsai Society in Roanoke, Virginia. Her first contact with the Arboretum occurred in 2001 when her club began participating in the annual Carolina Bonsai Expo. As a result of that participation, I started visiting the Hinoki group to conduct bonsai educational programs. My first visit in spring of 2002 began a back-and-forth reciprocal arrangement — the club coming to Asheville every year for the Expo and my going to Roanoke in return — that continued for the next eighteen years. Dana was actively engaged with the club and especially so during the Expo. Once she began attending the show she never missed one after that. On my annual visits to the Hinoki club Dana was front and center in the audience and always brought a tree or two for any critique or workshop program I conducted. Dana always treated me as if I was someone special, and, in turn, I was always on my best behavior around her so as not to spoil her delusion.

When the Arboretum was fundraising to build the Bonsai Exhibition Garden, Dana made a significant financial gift, earning the naming rights to the Circle Garden in the upper plaza. She chose to honor her late husband, Bunky, by dedicating the little garden in his memory. Over the years Dana made numerous other monetary gifts to the Arboretum, always directing her support to the benefit of the bonsai program. She also donated many bonsai containers and trees from her personal collection. Most of these were liquidated at auction, generating further funding support, but some of her donations were retained to become part of the Arboretum's bonsai holdings.

Here are some of the bonsai Dana Markham gave that are now in our collection:

Japanese white pine (Pinus parviflora)

Japanese Hornbeam (Carpinus japonica)

Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana)

Purple cutleaf maple (Acer palmatum v. dissectum atropurpureum)

The large cutleaf Japanese maple was Dana’s pride and joy. She displayed it at the 2005 Carolina Bonsai Expo and then donated it to the Arboretum. The specimen went straight out on display in the bonsai garden, which was newly opened at the time:

The following gallery shows the cutleaf maple first coming out in spring and then gradually changing foliage color as the growing season progresses (click on any image for larger view):

Dana Markham posed next to her cutleaf Japanese maple, on display in the bonsai garden. Dana was rightly proud of this bonsai, which originally grew as a landscape specimen in her yard.

Dana was a true lover of all sorts of plants, but especially bonsai. Even as she reduced her bonsai collection by sending much of it to the Arboretum, she was constantly acquiring new ones because she always had to have bonsai around to look at and tinker with. The trees she brought to my workshops for the club were always interesting subjects, whether for the type of plant or the age and development they exhibited.

On one occasion seven or eight years ago, Dana brought in a Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) that was young and shrubby and only minimally trained. This tree had numerous long, leggy limbs including several at the very top that formed a gangly crown. I noted this pine wasn't as developed as the trees Dana typically brought to the workshop, so I figured she wanted advice as to how to start it on a bonsai career. I told Dana that she should cut the tree back hard, sort of hit the reset button with it. You can handle Virginia pines that way because they are one of the few pines that will readily push out new growth on old wood. That feature allows them to take more pruning than most pines should get, and they will respond in a manner more in keeping with what you'd expect from a deciduous species. Dana wasn't interested in doing that. She would typically go along with my styling suggestions, but not this time. She wanted to work with the tree more or less as it was, leaving the gangly branches but doing something with them to make them look better.

There wasn't much to be done. My practice in workshop programs was to avoid dictating to the owner of the tree exactly what they should do with their plant, unless that was what they wanted me to do. I preferred to hear the owner's idea, then try to help them get to where they wanted to be. My choice with Dana's pine would have been to strip it down to a basic framework of trunk and greatly reduced branches, with just a little foliage left to help carry the tree along until it could push out new buds. I didn't think this particular specimen offered much, anyway. But it was her tree. If Dana wanted to work with it as it was instead of trying to make it better by essentially starting over, so be it. The Virginia pine was only minimally pruned in that session but then all the long branches were wired. Dana asked me to do the bending of the branches so I did. I twisted and looped them and compressed them in an accordion-like fashion, trying to reign in the little tree's sprawling habit. This technique is sometimes used on older pines that have gotten leggy, as a way of keeping them in the game. It didn't make much sense to me to do this with a young tree that didn't have any outstanding character worth trying to preserve. I thought the outcome of this effort to be little more than strange looking, but Dana liked it.

In spring of 2019, during my annual visit to the Hinoki club, Dana offered another tree donation. The tree in question was a nicely-developed old Swiss mountain pine (Pinus mugo):

I thought this specimen would make a good addition to the Arboretum collection, so I expressed interest. Then Dana said she wanted us to take the strange looking Virgina pine as part of the deal. I said okay, we would take them both, but the Virginia pine would probably wind up being auctioned. Dana said she wouldn't like to see that happen. She said she wanted me to take the Virginia pine to the Arboretum and live with it for a while, and, after that, if I still didn't think it had any merit, she would buy it back. I wouldn't agree to such an arrangement under other circumstances, but Dana was Dana and I went along with her wishes.

The Virginia pine sat out in the hoop house these past nearly five years, getting little attention beyond watering and fertilizing. When I learned of Dana's passing, I decided to work on that tree as a way of honoring her and all that she did to support and sustain bonsai at the Arboretum.

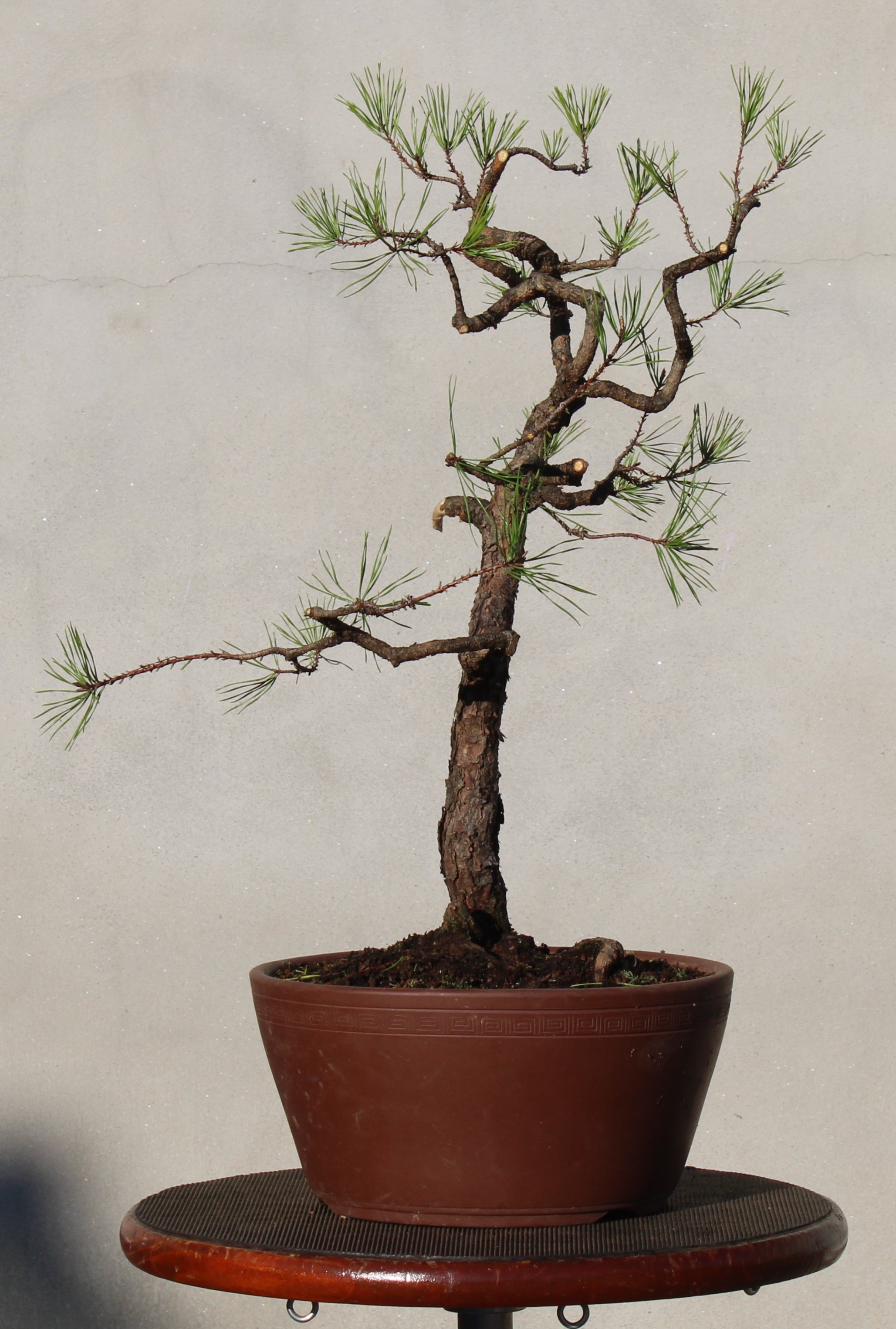

The gallery below shows the Virginia pine as it looked at the beginning of this most recent work session (click on any image for full view):

To start with, the pine was thoroughly pruned, stripped down to bare essentials. Without Dana looking over my shoulder and telling me I shouldn't, I entirely removed a couple branches for which I could see no good use. Otherwise, however, I decided to keep going with the general theme of a tree exhibiting an exaggeratedly convoluted shape. The scrawny limbs wired and contorted in the long-ago workshop session had over the years become more substantial, growing stockier and carrying a lot more foliage. Their overall length was excessive, though, so they were shortened. The big issue with this subject is found in the upper section of the tree, where the trunk divides into two distinctly separate lines. I would have removed one of them years ago, but now I felt obliged to keep them both because the loss of either would leave a huge void (click on any image for full view):

Next, wire was applied to every branch remaining, before all were adjusted for shape and positioning. I tried to carry forward the same character initially given to the branching so the tree in its entirety would be consistent in feeling (click on any image for full view):

What an unusual shape for a bonsai! It would be a fantastic shape for any full-sized pine, too, but not an impossible one. These photos of the crowns of old longleaf pines (Pinus palustris) suggest exaggerated contortion of limbs can occur:

Here is something to consider: this Virginia pine has nothing going for it except its unconventional shape. It is still a young tree, but imagine it twenty years from now if development continues along the present course. Imagine all those twisting, turning limbs being mature, bulked-up and filled out with secondary and tertiary branching. Love it or hate it, anyone who came across such a bonsai would wonder how on earth it got to be like that. It would be fascinating just for being so different. Dana never said what attracted her to this particular tree in the first place, or why she wanted it handled differently from any other bonsai of hers I ever saw, or why she was insistent that it come to the Arboretum.

I should have asked her when I had the chance because now we'll never know.