American Bonsai Pots - Part 2, Right Here, Right Now

It was good fortune to have connected with Sara Rayner early on in the Arboretum's bonsai endeavor. The quality of her work was very good, as good as anyone's in the United States, so my first impression of American bonsai pottery was as positive as could be.

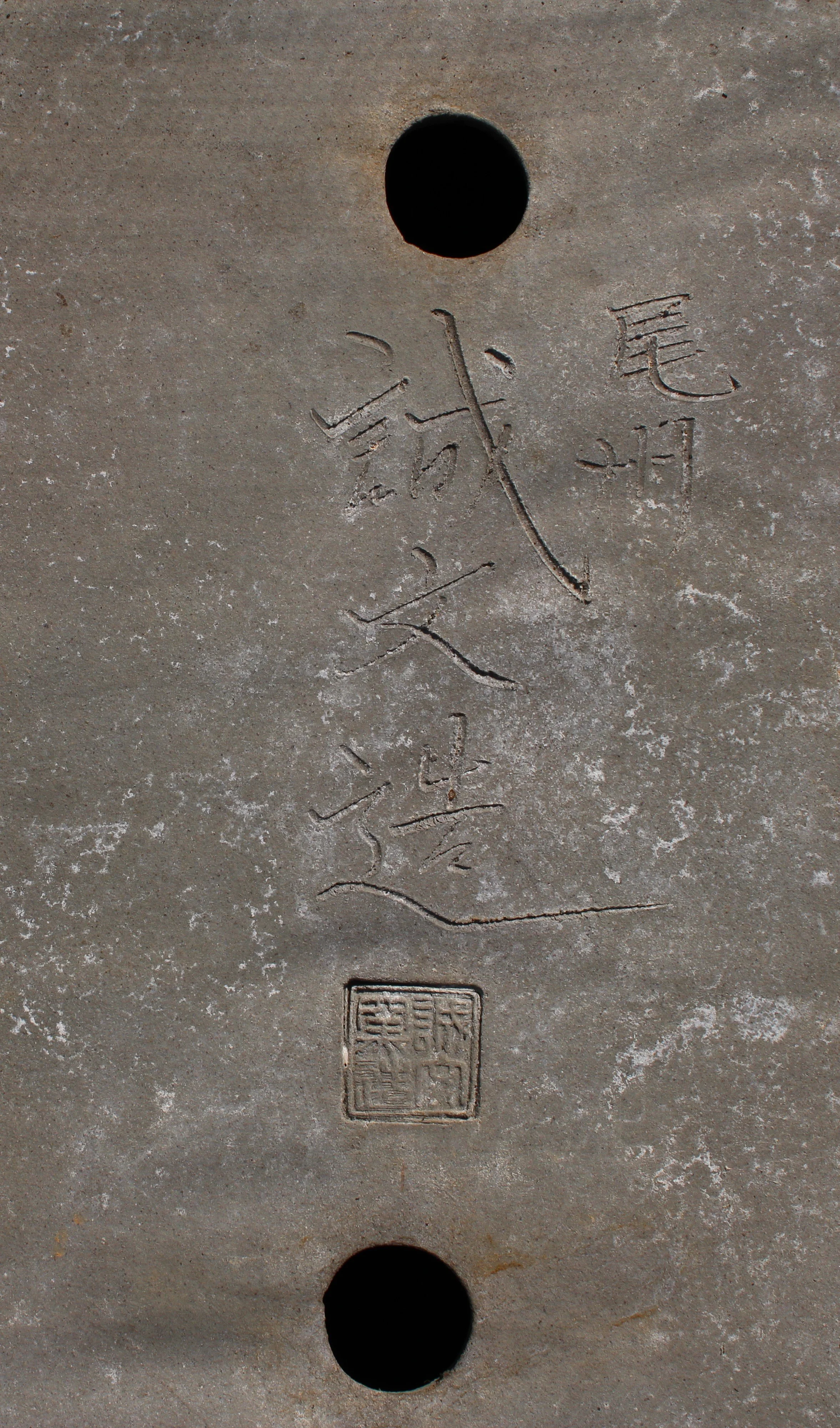

When I considered Sara Rayner's pots side by side with the imported pots we had, it wasn't exactly an apples-to-apples comparison. Sara's pottery was made by hand, predominantly wheel-thrown, and even though she sometimes made multiples of the same design, she was working by herself so every piece was her individual product. The majority of the imported pottery we had was production work of a different sort. Those pots were made by people’s hands but in essentially a factory setting, much of the work cast in molds. No doubt, there was better quality handmade bonsai pottery available in Japan, but I did not have ready access to it. (Bear in mind, dear reader, this was during long ago times when the Internet was only a rumor.) The importer with whom we sometimes did business offered an economy line of pottery and a more expensive line, and there was a noticeable difference in quality and price between the two. The more high-end containers were finely crafted, often featuring the mark, or chop, of the kiln where they were manufactured. Sometimes they featured hand-drawn Japanese characters etched in the clay on the bottom of the pot, apparently the signature of the individual who made it. I say "apparently" because I could not read the characters and had to rely on information from other people who knew more about bonsai containers than I did. As a consumer of imported bonsai pottery, I was operating from a position of inexperienced ignorance and therefore dependent on the importer to navigate the foreign pottery market for me. I could tell the difference between a higher end container and a production pot by the craftsmanship, but the elemental forms of both seemed largely the same.

Chop and signature on the bottom of a Japanese bonsai pot (image may be upside down).

I might have chosen to devote some time and energy to learning more about the Japanese bonsai pottery industry, as a means of securing higher grade goods for the Arboretum's collection. It was possible to do that and other Western bonsai people did. These people, whether professionals or dedicated enthusiasts, were able to make better connections for acquiring higher-quality bonsai containers from Japan. These same people sometimes also disappeared down a rabbit hole into the fascinating world of Japanese and antique Chinese bonsai pottery, where a person can get lost in the esoteric minutiae of a centuries-old tradition. Following such a track was not appealing to me. I did not have any extra time or energy to devote to it, and I wasn't interested enough in Japanese bonsai pottery to go to any great trouble learning everything I could about it. American bonsai pottery was more accessible in that regard because it didn't have as much historical baggage. All that mattered with an American pot was whether I liked it. My primary interest was in the little trees themselves, because I'm more naturally attracted to horticulture than to ceramic ware. Still, pottery is fundamentally important in bonsai, for all the reasons previously mentioned.

There was another aspect to my being open to the idea of using American bonsai containers. When I was first learning bonsai, I quickly caught on to the premise that there was a certain look for the little trees that was deemed most desirable to attain. The very foundation of that look was always an austere bonsai pot in one of the refined, iconic forms that carry with them the essence of deep tradition. Those pots were made in Japan or China and their character was part of the whole “Ancient Art of Bonsai” package. In the beginning this was not a problem. The desirability of producing bonsai that adhered to a certain conventionally approved form was only another of the rules in a game I was learning to play. If having a certain kind of pottery produced the right effect, it was easy enough to use those kinds of pots. After some time, however, an unanticipated dilemma arose. An unsettling feeling came to me that I didn't really like the look of the traditional stuff; not just the traditional pottery but the whole "traditional" concept. I struggled to come to terms with this because it presented obvious professional problems, even as I became more curious about alternative possibilities.

When the Arboretum began doing business with Sara Rayner and some of our bonsai were potted in her containers, I noticed that her work made our trees present a little differently. I liked the character of her pottery because it seemed less formal. The quality was there and Sara's design sense has always been refined, but the feeling of her work was warmer and more personable than that of traditional bonsai containers. When the bonsai I was shaping were planted in her pots, it seemed to me the trees looked more at home than they did in the imported containers. It wasn't a case of deciding traditional pots aren't good, but rather that Sara's containers were more appealing. The Arboretum's trees and Sara's pots had something in common — both were contemporary interpretations of a borrowed tradition, made in America.

Once it became evident that Sara Rayner's pottery was a good fit with our trees, we bought more of it. I also began to seek out other American bonsai pottery at shows and conventions. A lot of what I saw in the beginning was not so sophisticated and often small in size. Occasionally I'd come across a potter selling better quality handmade pots with a little size on them and I'd make a point of buying some of their work for the Arboretum's collection. I carried on that practice for years, and in so doing came to meet Dale Cochoy (Ohio), Ron Lang and Sharon Edwards-Russell (Pennsylvania, then North Carolina), Jack Hoover (Rhode Island), Preston Tolbert (North Carolina), and Byron Myrick (Mississippi). Other American bonsai pots came to us in donation, including some nice examples of work done by some of the earliest American bonsai potters to achieve notice, people like Max Braverman (Washington), Don Gould (Pennsylvania), Tom Dimig (South Carolina), and Jim Barrett (California). In the days of the Carolina Bonsai Expo, I made a point each year of inviting several American potters as vendors. Eli Akins (Georgia), Michele and Charles Smith (Georgia, then Tennessee), Ross Adams (Pennsylvania), Mark Issenberg (Tennessee) and Richard Boggs (North Carolina) all came to the Expo to show and sell their pots. Some of these potters donated work to the Arboretum and we purchased work from all of them.

One tremendously fortunate pottery connection the Arboretum made occurred when Robert Wallace first came to the Carolina Bonsai Expo in 1999 and caught the bonsai bug. He began learning bonsai and then, after awhile, started making bonsai pots for his own trees. Once he felt like he was getting the hang of making bonsai pots, he brought a few around to the Arboretum to show me. Rob's early efforts were smaller containers, but they were done with care and he was obviously dedicated to learning all he could and improving with each effort. Rob has a Bachelor's degree in Painting and Art Education, and makes his living teaching art, so he brought his formally trained sensibilities to his pursuit of bonsai pottery. The Arboretum started purchasing Rob's work in 2006 and has continued to do so up to the present day. Along the way, Rob went back to school and picked up his Master's, focusing on ceramics and bonsai, and their connections to art education. Not surprisingly, his bonsai pottery has become increasingly accomplished and I reckon by now he must be one of the best bonsai potters in the United States.

The Arboretum's bonsai collection includes a lot of Rob Wallace containers, more than the work of any other potter, owing to his proximity (Rob lives just down the road in Columbus, North Carolina) and the relationship we built with him over nearly two decades. It helps that Rob has mastered the difficult challenges posed by producing large containers, which for a number of reasons are more technically demanding to make. Large containers are something we can always use, and relatively few other bonsai potters have the ability to produce them. Our bonsai pottery collection also includes a lot of Sara Rayner's work, due to its now world-recognized quality and our many years of doing business with her. Ron Lang is another potter well represented in our holdings, and we had him as Guest Artist at the 2019 Expo, which focused on American bonsai pottery. We have work by many other American potters, too, and I'm always on the lookout for more.

It is a point of pride that at any given time when the Arboretum's bonsai collection is on view in the bonsai garden, about ninety percent of the trees displayed are in American bonsai containers (a few of our bonsai are planted on stones and one or two are still in imported containers). That is a distinction no other public bonsai display in the United States can claim. There was never any intention that we should follow that path, but we found ourselves on it and it has brought us to good place. Our bonsai collection is a consciously American expression, so having our trees in American bonsai pots is a perfect complement. The bonsai tradition in which we started and from which we've moved on, is about someplace else, some time long ago. Bonsai at The North Carolina Arboretum is about right here, right now — this place, this time. American bonsai pottery often has that same spirit.

The following is a sampling of American bonsai pottery in the Arboretum’s collection. The name of the potter is given under each image:

Sara Rayner

Robert Wallace

Dale Cochoy

Sara Rayner

Robert Wallace

Michele Smith

Mark Issenberg

Byron Myrick

Byron Myrick

Sharon Edwards-Russell

Ross Adams

Charles Smith

Charles Smith

Richard Boggs

Sara Rayner

Sara Rayner

Ron Lang

Ron Lang

Dale Cochoy

Preston Tolbert

Robert Wallace

Byron Myrick

Ron Lang

Ron Lang

Dale Cochoy

Don Gould

Dave Lowman

Eli Akins

Eli Akins

Bob Pruski

Ron Lang

Richard Boggs

Sara Rayner

Robert Wallace

Byron Myrick

Ross Adams

Sara Rayner

Robert Wallace