Long Tall Flat Top Baldy

My friend John Geanangel is a bonsai semi-professional. That is to say, he has other employment by which he makes his living, but he’s invested way too much in little trees to get away with calling himself a bonsai hobbyist. He spends all his available time working on his bonsai, sells a few trees, mostly to open up space on his benches so he can acquire replacements, and has a few students. Bonsai is his passion and everything else falls into place behind that.

Bonsai is how I met John. He was a member of the Bonsai Club of South Carolina back in 1994 when I first made contact with that group, and he was at the club meeting in 1995 when I first traveled to Columbia to do a program. I visited that group and its later incarnations annually for twenty five years and John was always there. He was also one of a very select few people who participated in all twenty four Carolina Bonsai Expos. John and I, and our mutual friend Ken Duncan, often did demonstrations together at the Expo, and on occasion the three of us would go hiking together. We went to observe nature, studying big trees for the sake of learning how to make better little trees.

Part of John’s enjoyment of bonsai involves collecting wild trees to be made into bonsai. His favorite plant material is baldcypress (Taxodium distichum). Much of South Carolina is baldcypress country and John knows places in the swamps where naturally dwarfed specimens can be found and potentially collected. The process is not a simple nor necessarily safe one, but John’s been at it a long time and knows what he’s about. I’ve never gone collecting with him. I’ve seen what he comes back with, though, and have long marveled at both the quality of the material and John’s ability to work with it to produce outstanding bonsai specimens. A few of these collected specimens eventually wound up being displayed at the Expo.

Here is a photo of John standing beside one of his collected baldcypress bonsai at the 2013 Carolina Bonsai Expo:

October 2013

The green ribbon displayed with the tree announced it to be that year’s “People’s Choice” award winner. Visitors to the Expo were encouraged to vote for their favorite bonsai and in 2013 John’s baldcypress won hands down. Small wonder — the specimen is big and obviously old, and to see such a tree growing in a container defies belief for the average person. As seen in the photo, John’s arm was in sling at the time. He was recovering from a serious arm injury, but still lugged that big baldcypress tree up to the Arboretum for the show.

Anyone interested in knowing more about how this tree was collected and developed can learn a great deal about it by visiting John’s YouTube channel. I don’t think he’s active on YouTube any more, but for a number of years John posted many videos there, and this tree was featured in a whole series. The collecting was documented here. Several videos documenting the development begin with this one.

That same baldcypress was also part of the now legendary display that John and Ken did as part of the 2015 Expo, staged in one of the Arboretum’s water features. All the baldcypress used in the display were trees collected by the two of them:

October 2015 Photo by Dr. Feliciano Jusay

John brought that same tall, straight baldcypress back to the final Expo in 2019, where it once again won the “People’s Choice” award. At the conclusion of the show, as all the exhibitors were busily taking down their displays, John approached me and asked if the Arboretum would be interested in having the tree. If I had my wits about me I would have made a disapproving face and said, “No I don’t think so”, just to see my friend’s reaction. As it was, my response was something more like, Wow — really? Are you sure? Of course we want it! Thanks! When John drove back to South Carolina that night his big baldcypress stayed behind in its new home.

In 2020 John’s tree was out on display in the Bonsai Exhibition Garden for the entire year, where it quickly became a favorite of our visitors. I took pictures of our new treasure as it went through the progression of seasonal change:

May 2020

May 2020

July 2020

A tree like this really ought to have a poetic name. I think Long John is pretty good, but there’s at least one person I can think of who wouldn’t approve.

The big baldcypress has become a regular feature in the bonsai garden, virtually always on display whenever we have trees out. The following selection of images were made over the last four years:

September 2021

November 2021

August 2022

October 2022

November 2023

November 2024

Grateful as I am for John’s gift (and I’m sincerely thankful for all the donations that have made the Arboretum’s bonsai collection possible), and as much as John is my friend (I don’t have enough friends to afford losing any), it’s still my job to look critically at all the trees in our collection. This impressive baldcypress is no exception. After studying the tree for a year I decided it would look better being presented in a slightly different way. Here is a view of the top of the tree from the preferred viewing angle as it was when we received it:

I thought the crown of the tree had a somewhat static look when seen this way. The branch layout was not symmetrical, but felt like it was because of the way the trunk was cleaved at the top with a branch coming off each half. The two branches were of relatively equal visual weight and veered apart at approximately the same angle. This was not, in fact, the true structure of the tree. It only appeared that way when presented as it was. With a slight clockwise rotation, a third branch came into view and gave the crown a more dynamic appearance:

Making such an alteration is a simple matter — or ought to be. All that is needed is to rotate the tree a little next time it’s repotted. When I repotted the baldcypress in spring of 2021 I tried to make the adjustment and found it was not possible. The tree had come to us potted in a fine rectangular stoneware container made by Sharon Russel-Edwards, and it was a tight fit. So tight, in fact, that the tree could only be placed in it one way! The great, flaring base of the tree was irregular, with one particular surface root that projected outwards more than any other. The placement of the tree in the container was driven by the need to accommodate that one surface root. If the baldcypress was to be in the fine rectangular pot, the tree would have to be presented as it was or the pot would have to be presented in a catty-cornered fashion. I wasn’t going to show the pot that way and I didn’t have a larger pot appropriate to this specimen. The tree went back into the same container. I started working on the branch structure instead, hoping to achieve a more asymmetrical crown by way of pruning. The results were modest. Don’t misunderstand; I like the structure of tree’s top just fine. It shows the effect of more than fifteen years of development, both John’s work and mine. The problem exists only when looking at the crown from the perspective of how it’s usually presented. Here is a view from below, showing the highly naturalistic character of the branching:

2023

For five years I kept the tree in the rectangular pot, always thinking it was unfortunate to be locked into only two ways of showing the specimen — either front or back. This baldcypress might be enjoyed from any number of different perspectives. Then just a month ago I paid a visit to the studio of North Carolina potter Preston Tolbert and purchased a large round pot with a ruggedly textured finish:

I had the thought when buying the container that it might be right for the big baldcypress, but I couldn’t be certain until I brought it back to the Arboretum and eyeballed the pot next to the tree. The combination looked like a winner to me.

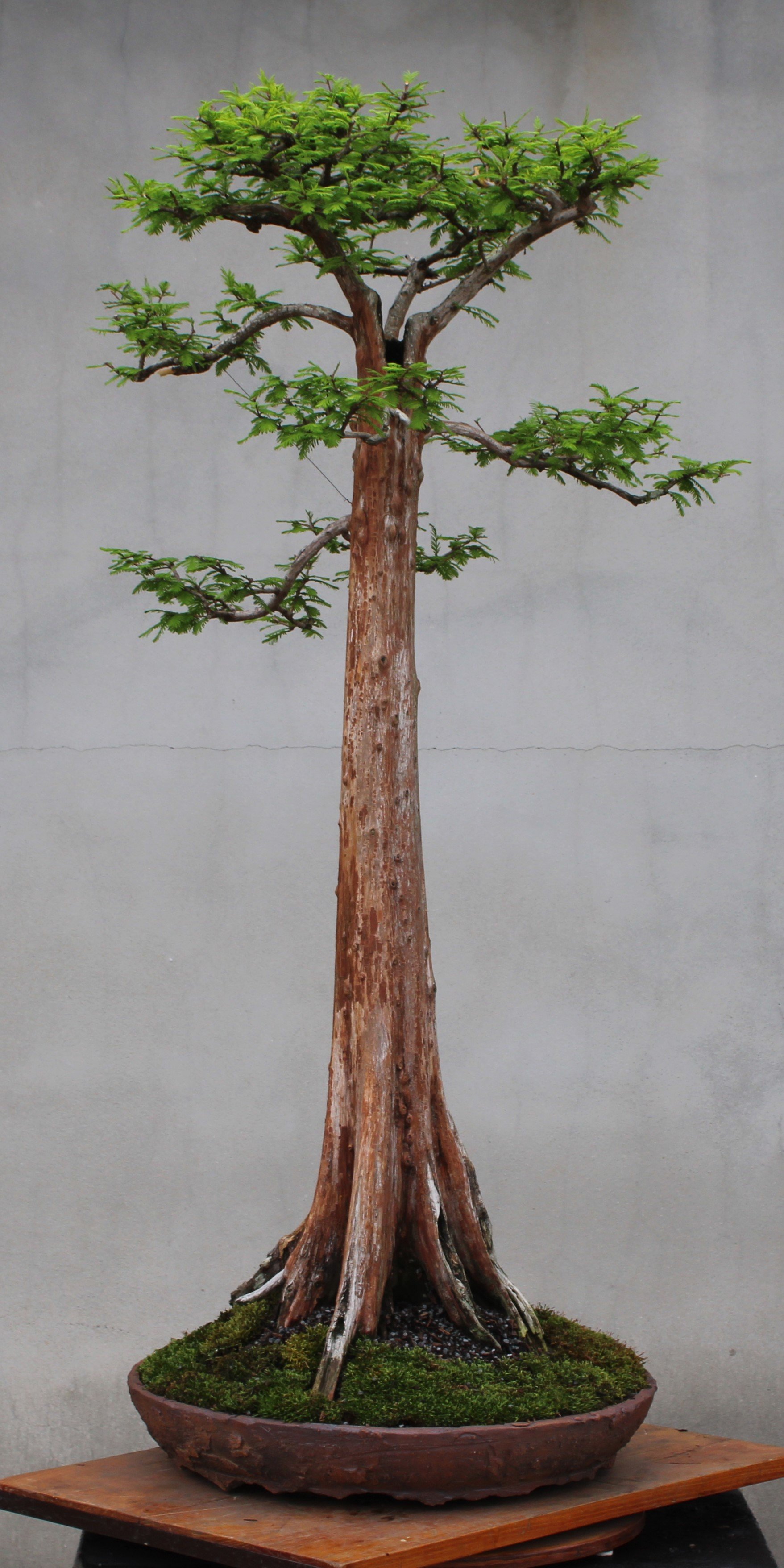

Here, for the first time in its new container and presented as I’ve long thought it should be, is the Arboretum’s only collected baldcypress:

May 2025

Here is a selection of alternative views made possible by the round container, any of which I could comfortably live with:

If you watch the videos John made of his styling work on this tree, you can see how he developed the primary structure of the crown from a cut-back stump. Here is a closeup view of the critical point at which the trunk was first chopped, seventeen years later:

The periphery of the old cut has calloused nicely and now looks completely natural. In reaction to having its trunk chopped and its biggest roots cut off, however, the tree is now almost entirely hollow. That doesn’t pose much threat to the long-term health of this specimen because it’s a baldcypress. The oldest baldcypress in the world is hollow, too:

Ancient baldcypress in Three Sisters Swamp

Although I’ve spent a good deal of time fussing about the crown, the real attraction of this specimen is its old trunk, and especially its widely flaring base. To my knowledge, baldcypress only develop this characteristic fluted form when growing in saturated earth — I’ve never seen it produced otherwise. Such a base is naturally a great attraction for those who collect baldcypress from the swamps. However, collecting these specimens requires cutting the tree’s roots severely. Any time a sizable old limb is cut, be it root or branch, some amount of die-back is almost inevitable.

Here is a closeup of the base of this baldcypress in 2013, five years after collection and the first time John displayed it at the Expo:

Here is an image of the base of the tree today, nearly twelve years later, from almost the same perspective:

Die-back from the big roots being chopped has clearly occurred. In all likelihood, the die-back had already occurred in 2013 but was not yet visible. Bark can hold on a long time. Having no experience with collecting old baldcypress from the swamps, I can’t speak on the topic with any certainty. My guess, however, is that many or most trees collected under those circumstances eventually end up the same way — with die-back evident in the fluted base of the tree. I suppose it would be better if this didn’t happen. Fortunately, all evidence suggests the die-back in this case has stabilized and poses little risk horticulturally. It’s not so much of a concern to me aesthetically, either, because I understand why it happens and don’t find the look unappealing. In fact, I’ve come across a tree in nature featuring something of the same look and found it quite memorable:

The tree in the above photo is not a baldcypress. Rather, it’s a dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) growing at the US National Arboretum. The two tree species are distantly related, both belonging to the Cypress Family (Cupressaceae), and share numerous physical similarities, so it’s not a totally unfair comparison.