Black Pine Progression - Part 3

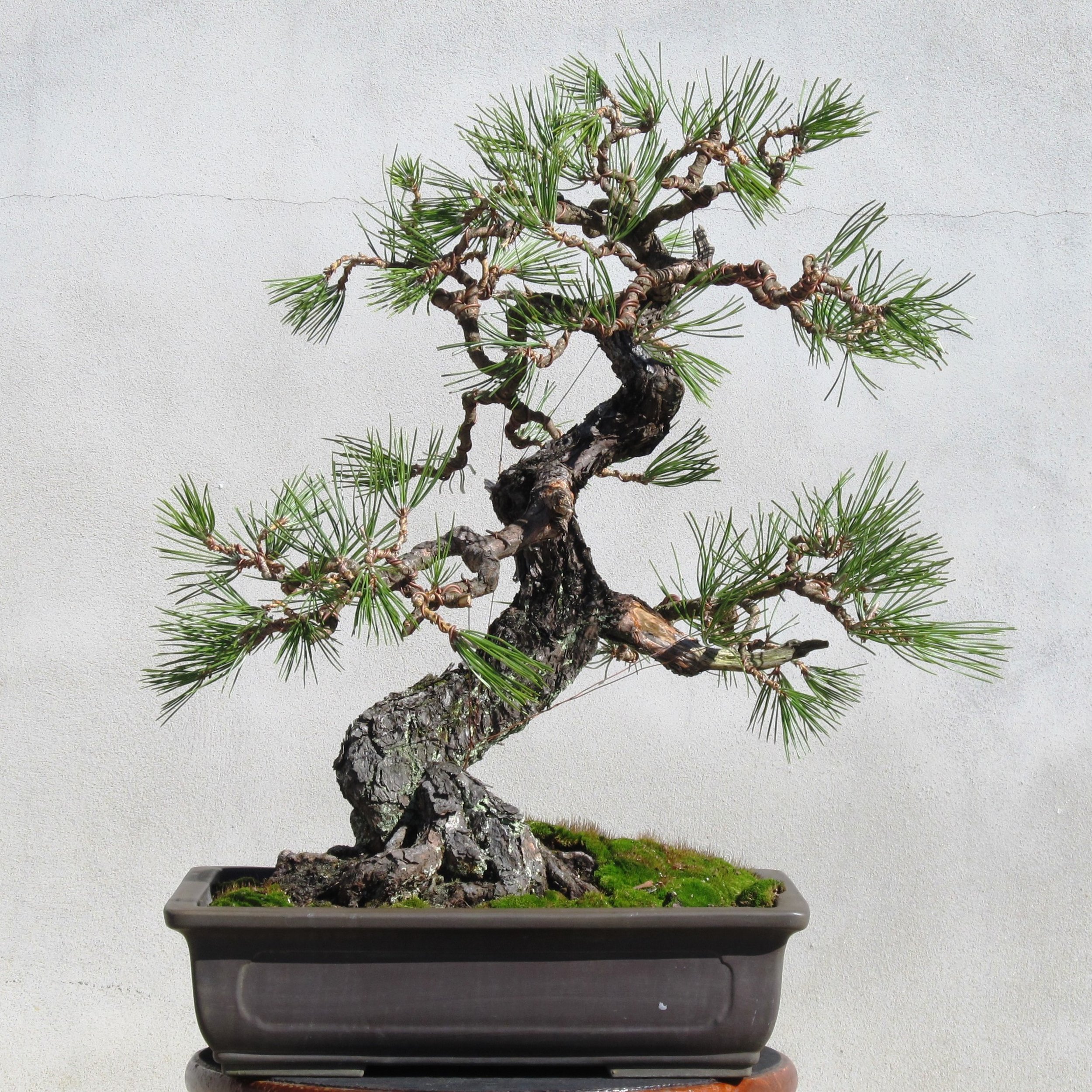

2016 was a watershed year for the pine that is the subject of this specimen profile. It began with a major restyling (pictured below on the left) and by the end of the year the tree had regrown, gaining lots of healthy foliage but losing definition along the way (pictured below on the right):

Within a few days of making the first round of November 2016 photographs (shown in last week’s Journal entry), this second batch was recorded:

There is something very appealing in the look of a bonsai that has just been thoroughly worked over during the dormant season. It looks purified somehow, and, unlike a newly pruned specimen in the growing season, it will stay that way for a while. There is time in the winter to work slowly, with exactness and care, to clean up not only the tree but also the essential lines of the composition. There is time then to look, and here I want to say to think, but it is more like feeling than thinking. There is time for it, anyway. You look and consider: How do you feel about what you see? Move this branch a little that way … better. What if you were to remove this part here altogether? Maybe ... but maybe not. Don't do it now, but make a mental note. Remember it and maybe consider it again another time. In winter you can work like that, taking time and considering options, bringing the big picture into clearer focus by stripping down the tree to only what is necessary and then organizing the details. The tree is dormant and will remain so for awhile, like an anesthetized patient. Take your time, get it right.

The work done in November of 2016 followed up on and reinforced the work begun in January of that same year. Here is a side-by-side comparison of the same view of the tree after each session:

The primary objective is to compress the crown. Sometimes this is done by removal of branch extremities, but other times the shortening is achieved by wiring a branch and contorting it — corkscrewing it in effect — to draw it in closer to the trunk. This not only makes the crown tighter, it accurately reflects the look of truly old trees in nature. Here is an image of the crown of a longleaf pine that is several hundred years old:

Branches of old trees are seldom straight and orderly. They go up, they go down, they twist and turn, they angle back in toward the trunk; they grow any way possible in order to hold foliage out for maximum exposure to sunlight. The challenge to the bonsai stylist is to capture this look while maintaining some semblance of order for aesthetic purposes. How much order is necessary to make a bonsai look artistically appealing? This is in the eye of the beholder, and tastes vary. By the time of the stylings that took place on this black pine in 2016 my personal tastes were moving toward a greater embrace of disorder. But this sense of loosening up should not be confused with chaos. There is still very much an ordering to this tree's branch structure, but it is less predictable and less contrived. In each succeeding design session I was feeling my way along toward its optimal realization.

The next set of pictures I have for this specimen date from February of 2018:

The four images above show the tree in quarter turns, beginning with the view that had always been thought of as the front, or best view. Here again we are seeing the tree immediately following an intensive work session. The foliage has been thinned out to a state of minimal density and all the branches have been wired and set in place. Since the last major restructuring in early 2016 this pine has followed the same general design path, with changes to its appearance becoming less dramatic. The objective is now refinement, not redesign.

Our black pine bonsai started out as a lackluster imitation of the classical Japanese example of its kind, but now had transformed into a naturalistic expression of an old tree in nature. One vestige of its neoclassical origins remained: the container in which it was potted. There is nothing wrong with a plain, traditional, Japanese-made rectangular bonsai pot. Like a room painted beige, it goes with just about anything you put in it. When it comes to personality, however, it hasn't much, which is exactly why it is so usable. I had decided at this point that the tree would be better served by a container that had something more to say for itself. The tree now had a personality of its own, and the right container could not only harmonize with that but also reinforce it, even amplify it. I went looking through the many available bonsai pots in the Arboretum's holdings and didn't find any that seemed right. I did, however, find a rock.

To speak more precisely, what I found was an interestingly shaped, slightly curved slab of material known as bog iron. I am not a geologist, so I am not the one to explain exactly how bog iron is formed. But it is a naturally occurring material, rock-like, from which the earliest forms of ironwork were produced when smelting was first developed thousands of years ago. The piece I found when I went looking for a pot is generally oval in shape, formed like a very shallow bowl, about 24-inches in length and half an inch thick. Its color is light brown, somewhere between a pale creamy mustard and rust. It had been given to us by a longtime friend to the Arboretum named Felton Jones (who deserves and will one day have an entry of his own in this Journal). Felton thought the bog iron slab would make an excellent planter for the right bonsai, and donated it for that purpose. I can't say exactly when he did that, but I never had found a use for it. By the time I rediscovered the slab it had been in storage for about twenty years and, out of nowhere, its purpose was revealed.

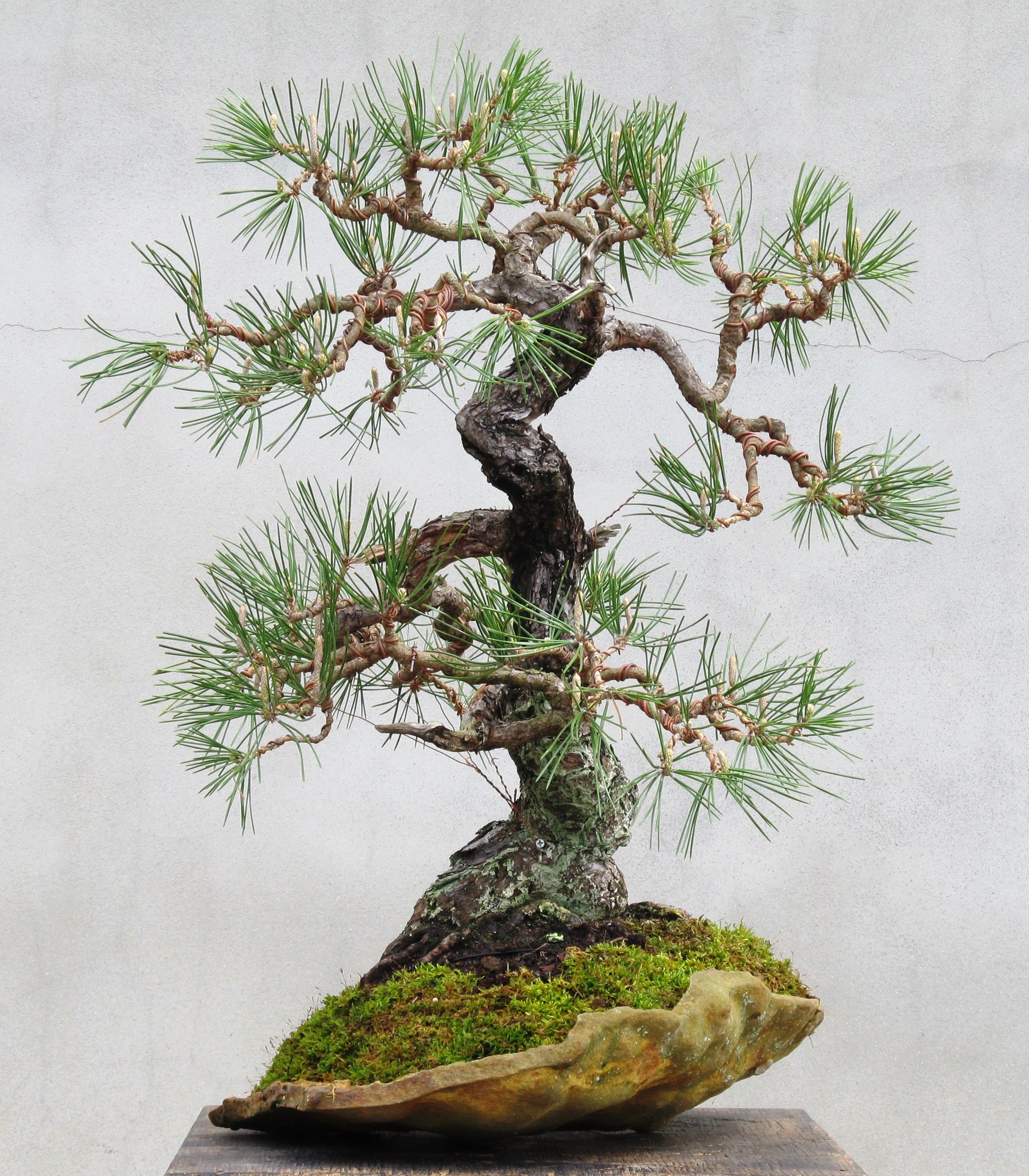

In April of 2018 the black pine bonsai was planted on Felton's bog iron slab:

When a thing is right its necessary components will fall into place. A long time back, when the black pine bonsai was in its earliest stages, Felton had once helped me work on it. I doubt when he gave us the bog iron slab he knew it would one day be the perfect fit for that same tree, but with Felton you never could say for sure.

This photo shows the pine in October of 2018, at the conclusion of its first successful growing season on the slab:

The tree as seen in the above image has a somewhat unkempt appearance. The branches are still wired at this point, still placed where they were in the photos made in April, so the difference is entirely in the look of the foliage. In April the year's new growth was still in its candle stage, but in October we see the end result. The needles are long, but no attempt was made that year to regulate their growth, since the tree was not on display and the primary concern was that it should experience strong growth and establish itself on the slab. But take notice that the new needle bundles all point upward, which is entirely typical of this species. This tendency can contribute to a look of being clumsy and overgrown.

In January of 2019 the whole process starts again:

There is a technique I now employ to make use of the strongly upward growth habit of new pine needles. It is visible to some degree in the set of images directly above, and is even more pronounced in these taken in November of 2020:

All branch endings are wired to point downward. It looks like the intention is to create a weeping form of pine tree. But when the candles emerge and new growth commences, the new foliage will reverse direction and head skyward as usual. The end result will be yet another convolution in the line of the branch, in keeping with the intended overall gnarly nature of the tree.

The conclusion of this pine story brings us up to the present, with the tree currently out on display in the bonsai garden for the first time in more than ten years. If you come by and see it you may find it displayed either of the two ways depicted below, because it has been shaped as a three-dimensional object and needn't be limited to a single front:

The needles are much shorter now. The technique for reducing their size involves pruning candles at a certain time in their development, but an explanation of the process will wait for another day. What matters more, and the reason for detailing the history of this specimen, is the degree to which it has evolved in the decades since it became part of the Arboretum's collection. More than simply the product of normal aging (any bonsai will change as it ages), this particular black pine transformed the way it did because the person who grew it over the course of that time experienced an evolution of aesthetic sensibility. Its look started out as an imitation of a standard form and ended up as an expression of personal experience. That's why this pine might be viewed as emblematic of the Arboretum's overall bonsai program — because the entire concept of bonsai at this place has followed a similar track of development.

There is much to say about this and the saying of it is happening right now, in the pages of The Curator's Journal.