The Hail-Mary

When I went to the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum I just assumed that Curator Bob Drechsler and his assistant, Dan Chiplis, knew everything there was to know about bonsai. They never presented themselves that way, but it made sense to me that the people responsible for the best bonsai collection in the United States must be among the very top bonsai authorities in the country. They, along with all the other people I met at the museum, treated me with such great kindness, good humor and patience that I imagined the bonsai community must be populated with only the most agreeable sort of people. I was aware enough to know the reception I received was due mostly to my association with Dr. Creech's good name. But Dr. Creech thought well of me and now his old associates in DC thought well of me, too. I felt welcomed into a new adventure and figured maybe I had a pretty high ceiling in bonsai, once I learned how to do it.

When I went to the World Bonsai Convention in 1993 my main purpose was to learn more about doing bonsai. Watching the invited artists present their demonstration programs was educational, so I did pick up a few new bits of information that way. What I really learned, though, was that the world of bonsai was much larger, more complex and more competitive than I ever would have imagined.

Much of my time at the convention was spent in the company of the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum contingent, and I was very glad they were there. They introduced me to numerous people of note, always pointing out that I was from a new arboretum in North Carolina and never failing to mention the Dr. Creech connection. The people I met at the convention were all polite, their responses to meeting me ranging from politely curious to politely indifferent. Somehow it surprised me that not everyone there knew Bob and Dan. I would have thought the curator and assistant curator of the national bonsai collection would be celebrities at this event, but they were often alone when I ran into them and seemed more anonymous than celebrated. A notable exception occurred one time when I was talking with Bob and a delegation of Japanese bonsai officials, including the Chairman of the Nippon Bonsai Association, Mr. Kato, came up to us. They gathered around Bob and bowed deeply. A spokesman said a few words on Mr. Kato's behalf and then gave Bob several exquisitely wrapped little presents. Then they all bowed again and moved on. Bob looked embarrassed. He chuckled a bit and said, “They're always doing stuff like that”.

It seemed right to me that the important Japanese bonsai people at the convention recognized Bob Drechsler and made a fuss over him. It seemed strange to me that he didn't get that sort of acknowledgment and respect more routinely. It impressed upon me the fact that in the greater world of bonsai an entity like the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum did not matter so much to everyone. It gave me pause to contemplate: If the national bonsai collection was not so important, what did my ragtag gaggle of rundown little trees amount to? If Bob Drechsler, twenty years the curator of the best bonsai collection in the United States, could be largely overlooked at a big bonsai convention, then why would anyone even notice the unknown caretaker of an unknown collection at an unknown arboretum?

The experience I had in DC was idyllic, like the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum was at the end of the Yellow Brick Road. The convention woke me from that dream. The world of bonsai was like all the rest of life — it contained the possibility of success and fulfillment, but there were no guarantees. Some people may be born at the top of the hill but I had never been one of them. It wasn't going to happen that way this time, either.

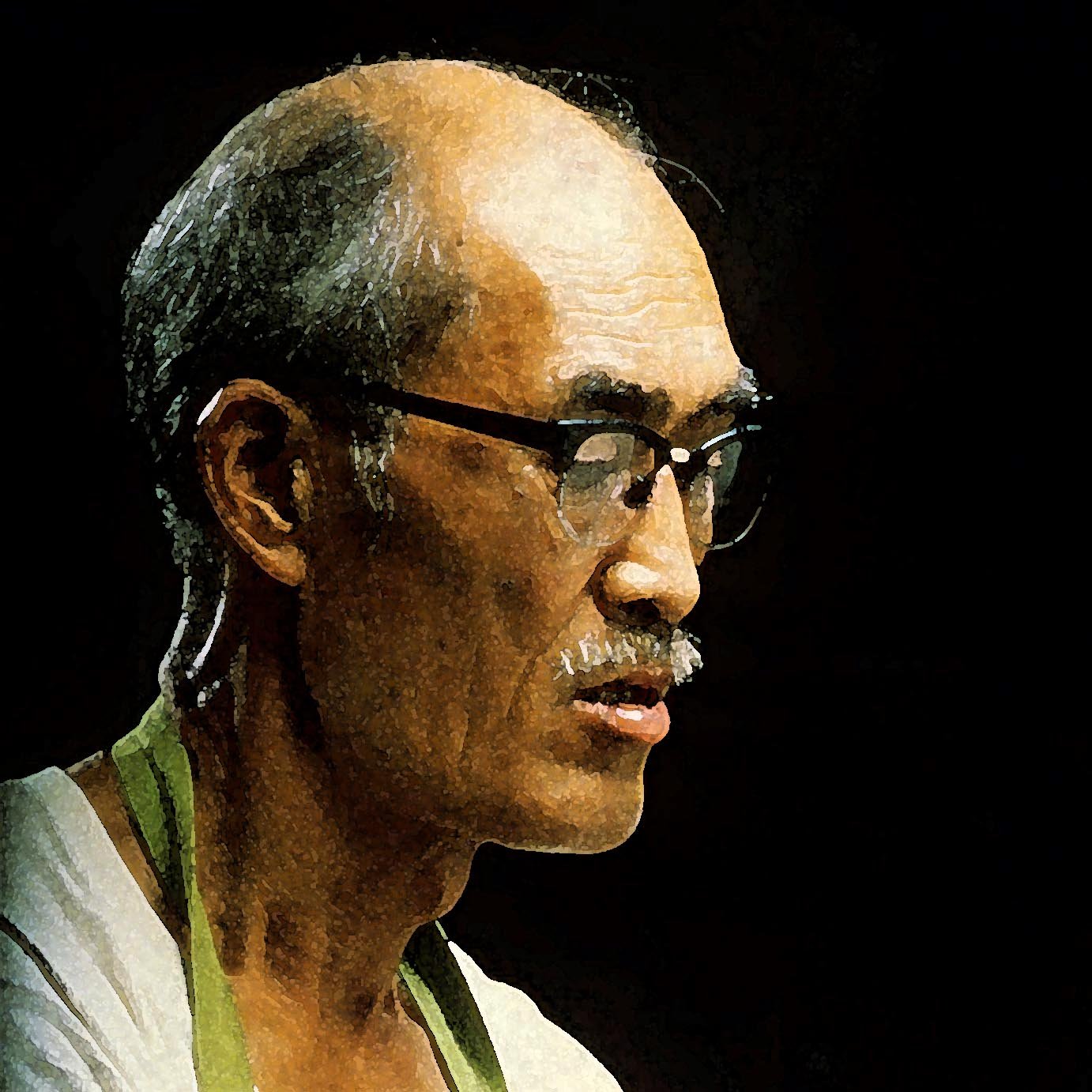

In 1994, even as I was working toward the goal of a regional bonsai community with The North Carolina Arboretum at its center, I was trying to accelerate my personal bonsai learning curve. Word reached me early in the year that Yuji Yoshimura was going to be in Charlotte, doing a workshop program for the Bonsai Society of the Carolinas. Ever since meeting Mr. Yoshimura at the convention the year before I had been trying to figure out how to pursue the tantalizing offer of personalized instruction with him. I was frankly too much in awe of Mr. Yoshimura to call him on the phone and say, “hey, remember what you said?” Now that he was coming to Charlotte, I saw my opening.

A few weeks prior to the workshop I wrote a letter to Mr. Yoshimura. It was formal and highly respectful in tone, addressing him as "Dear Sir." I wrote it with the assumption that he wouldn't remember me, so I re-introduced myself and reiterated all the information about where I worked and the bonsai donation we had received and how I had been selected to take care of it. I made certain to mention Don Torppa, who had known Mr. Yoshimura for years, and Dr. Creech and my study in DC. I mentioned Janet Lanman, too, remembering how strongly Mr. Yoshimura had reacted when I had previously dropped her name into the conversation. Janet had plans to come visit me at the Arboretum later that spring and I made sure Mr. Yoshimura knew that. Then, with the greatest possible humility and deference, I reminded him of his proposal that I might come to his studio in New York for a period of study. I expressed my belief that such an experience would be invaluable in helping me meet the challenge of my new career. I told him I had registered for his workshop in Charlotte and suggested that he and I might, perhaps, talk some about the subject of a study session when I saw him there.

The workshop was a worthwhile experience (previously written about in the Journal entry titled Twists and Turns in the Life of a Corkscrewed Juniper), although the total time I had one-on-one with Mr. Yoshimura was limited and not at all optimal. I managed to bring up the topic of studying with him but he responded by suggesting I could attend one of his public classes in New York. I gingerly pressed him on the possibility of personalized instruction, and he allowed such a thing might take place if he had an opening in his schedule. He didn’t say when that might happen, and he still did not make any solid commitment that it would happen at all. Mr. Yoshimura then asked me questions about my background, my work, my ideas about the future of the bonsai program at the Arboretum. He seemed to be considering me somehow, sizing me up, but he remained non-committal. I was frustrated and could not understand why he was being so elusive.

Back home, I put aside uncertainties and renewed my quest to learn all I could about bonsai. It was the start of the second growing season for the Arboretum's bonsai collection, and I had recently been given formal consent to spend a total of two days time dedicated to bonsai work per week. It was not two full days, but rather sixteen hours of bonsai work interspersed with my ongoing responsibilities in the nursery, with the nursery work having priority. This was still insufficient but represented progress from the original when time allows paradigm. I devoted a good deal of effort to working on the juniper I had taken to Mr. Yoshimura's workshop. Little had been done to it at the workshop, but I came away knowing the next necessary steps in the plan for its development. I was eager to show I understood the teacher's thinking and could do the work.

Pleased with the results on the juniper, I then painted a sketch of the bonsai in the form Mr. Yoshimura had described as its ultimate design. I had decided to write to him again, to once more entreat the old master to accept me as a student for personalized instruction. The painting provided a reason for reaching out. I had the feeling this was it; I'd either win over Mr. Yoshimura with my persistence or I’d annoy him to the point where he would finally just say no. I would take one more shot, put everything into it and one way or another there would be resolution. I wrote this letter by hand and made it as direct, honest and personal as I could:

Mr. Yoshimura did not keep me waiting too long. A little less than a month later, I received this reply:

Once again, Mr. Yoshimura had raised the possibility of studying with him at one of his regularly scheduled public teaching classes. But this letter included a single line with the words I needed to see: “…may be I could make special session for you in December - January '95.”

That was it. A commitment, sort of, in writing. And a time frame. It was going to happen.