The Age Thing Again - Part 3

Perhaps the most compelling physical feature of old trees is irregularity. Old trees are often crooked, bent, twisted, lumpy, asymmetrical and missing parts. These characteristics are the results of struggles with an unending variety of challenges faced by the individual tree over the course of a long lifetime. We can think of these challenges as the effects of environment, and this includes not only the physical characteristics of the tree's surroundings, but also anything that happens to the tree along the way. It is important in this regard to recognize the individuality of the tree, understanding that the exact sequence of events in the life of any single tree is exclusive to it. Starting out the tree is just another of its kind, shaped primarily by its genetic inheritance. A striped maple is a striped maple and a pitch pine is a pitch pine, and barring mutations (genetic irregularities) any particular specimen will have the same general physical traits as all the other members of its species. The type of foliage or bark, the propensity to grow tall or have a spreading crown, the strength of the wood and the tolerance for cold are all examples of traits predetermined by genetics. Variations can occur between individuals within a species or between isolated groups of the same species, but broadly speaking the members of any given species start out with the same stuff. Then life happens.

Let us look again at the example of the champion Osage orange at Mr. Henry's house:

We have already discussed the massive bulk of the lower trunk and its base and the appearance of the tree's bark. Now observe the condition of its crown, which is the structural mass formed by the branching coming off the trunk and primary branches. Overall the silhouette shape of the crown is broadly spherical, which is typical of the species. In this photograph the tree is in leaf so we can see only glimpses of the underlying structure. Still, we can see into the interior of the crown to some extent and in places we can look right through it and see the sky behind. The branching we can see within the crown is mostly curved and in some cases angular and heading in a variety of directions. If this was a younger tree the density of growth in the crown would be greater and more uniform, and the nature of the branches would likely be more straight.

Here is an image made from underneath the crown, looking up into it:

Genetics inclines the Osage orange to assume a certain pattern of growth, but then that pattern is affected by environmental influence. Two primary environmental factors are sunlight and gravity. Technically speaking, the tendency for plants to grow directionally in response to sunlight is called phototropism, while the influence of gravity on plant growth is called gravitropism. These tropisms have effect on all trees, but the effect itself can be influenced by other environmental factors, such as whether the tree in question is growing out in the open or is surrounded by other trees. The Osage orange at Red Hill is growing out in the open, which allowed for it to develop a wide crown. Branches could reach way out to gain access to the sunlight, and then gravity pulling on the weight of the extended branches caused them to grow downward. Always, however, the tree’s response was to grow upwards again, counter to the gravitational pull. Although this tree did not have to compete with other trees for sunlight, the various branches of the tree were in competition with each other. This caused branches to go this way and that within the crown to find their place in the sun.

Environmental influence often results in physical damage. Damage to trees is inevitable and presents itself in myriad forms, ranging from having the entire top of a tree torn off by a hurricane to having tender buds on the tips of small branches eaten off by squirrels. In all cases the tree is thwarted from growing as it otherwise would and must rely on the ability to regenerate new parts to carry on necessary life functions. These new parts will then be subject to the continuing effects of light and gravity and other environmental factors as they grow.

Looking at another interior view of the Osage orange we can see evidence of damage to a large branch and the resulting regrowth:

It might look like the one big limb simply reached a certain point and then divided itself into several smaller divergent limbs, but there was some sort of violent incident that caused this to happen. The damage was done long ago and the regrowth is old now too, so the look of it has all smoothed out. We might say it looks natural, and of course it is, although not necessarily in the way we intend.

Simultaneous to regeneration, any tree that suffers damage must attempt to isolate and cover the affected area in order to prevent insects and pathogens from exploiting the wound as an entryway to the tree's interior. The ability to replace lost parts and respond protectively to injury is genetic, by the way. Those are just a couple of the traits evolved by woody plants to cope with the vicissitudes of existence in nature. These response mechanisms leave telltale marks that can be read long after the fact. The process of damage and recovery goes on constantly in a tree's life, in ways large and small, and after many years the result is manifest in the physical character of each individual tree.

Referring again to the photo above, we can see evidence of yet another environmental influence: human activity. On the lower right-hand side of the large limb is the stub of a branch that was obviously cut by a saw. Just above that a thin, straight line is visible, which is a cable run from one part of the tree to another in order to protect against one of those long limbs breaking off. Not seen in any of the images is the lightning rod and grounding cable that is visible when one goes to visit the tree in person. If you do that, you'll have to stand outside the ropes that form a wide circle around the base of the tree to protect against people climbing up into it or compacting the soil nearby. Red Hill is a protected historic site and the big old Osage orange is a well-known feature on its grounds. People have taken an interest over the years and assumed a role in preserving the tree by acting in its defense, and their behaviors have helped to give the tree the appearance it presently has. Were it not for these interventions the crown of the tree might be much more irregular in its construction, or something worse may have happened. The world's largest Osage orange would likely not be as whole as it is today without the beneficial relationship it enjoys with humans.

I have had the good fortune of encountering a handful of other trees in the same class as the exemplary Osage orange. Each of them exhibits the hallmarks of a long life:

This gigantic American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) is hundreds of years old. It’s growing in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Bonsai artist Jim Doyle (right) lives just a few miles from this tree and has known it a long time. Jim was the one who brought me to see it.

Healthy old deciduous trees often feature complex ramification of branching.

An old growth Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) growing in the Middle Prong Wilderness in North Carolina. Because it is a forest tree it could not spread out like the big Osage orange and sycamore did.

The crown is held up high, towering over the younger trees nearby.

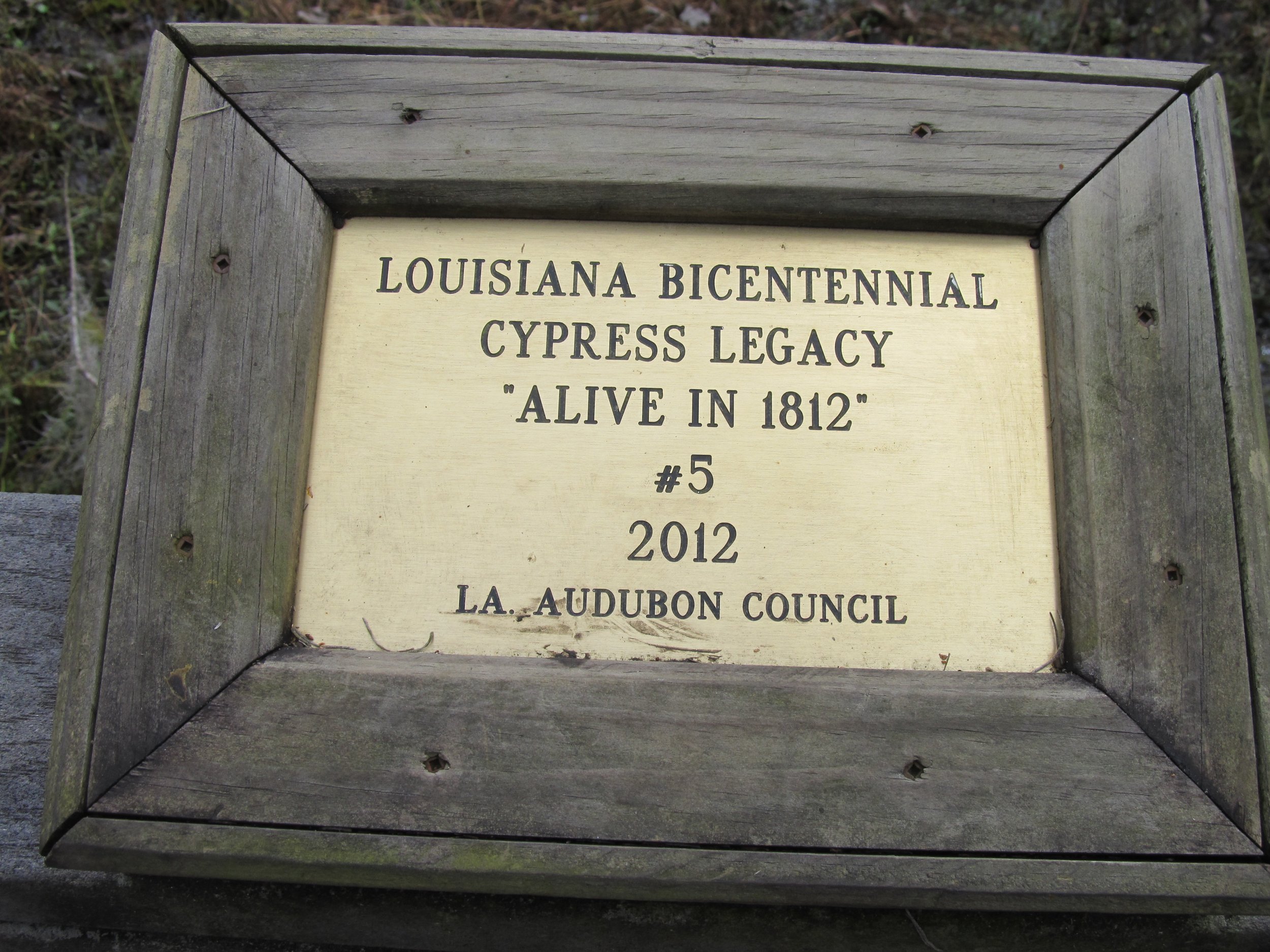

Old baldcypress can be found throughout the southeastern United States. This specimen lives in Barataria Preserve, near New Orleans, Louisiana.

As is typical of old baldcyress, the crown of this tree shows extensive damage and recovery.

This incredible Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera) can be found in Maymont Park, Richmond, Virginia. Note that the original top of this tree was lost a long time back to some sort of damage.

One of several leaders that form the crown of this tuliptree, large enough to be an individual tree in its own right.

So much character!

Longleaf Pines (Pinus palustris) growing at Weymouth Woods Sandhills Nature Preserve in Moore County, North Carolina. These trees are hundreds of years old.

A famous Live Oak (Quercus virginiana) known as the Constitution Oak, in Geneva, Alabama.

This tree was already mature when the US Constitution was signed in 1787.

When we look at an old tree what we see is the full expression of its genetic capacity as shaped by the accumulated effects of everything that has happened to it in its lifetime. No wonder old trees look amazing!

To be continued…