Who He Was - Part 2

As the new year began in 1959, thirty-seven-year-old Yuji Yoshimura began teaching bonsai classes at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. He'd arrived in America laden with all the bonsai materials needed because they would not be otherwise available. This amounted to more than a ton of baggage, and the whole operation must have required prodigious planning and organization. Those happened to be two of Yuji's strongest traits. Detailed planning and preparation would mark his professional habit throughout his career. Yuji taught numerous well-received classes in Brooklyn through the spring and autumn months. He also found time to travel in spring to Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania to teach a class there, and again the response was strongly positive. That summer Yuji traveled across the United States, teaching and promoting bonsai in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Denver and the San Francisco Bay area.

Here again, it is important to pause and consider context. Yuji, on the young side of middle-age, turns his face from all that is home and familiar and travels to a completely foreign land. He establishes himself in the biggest city in the United States, then travels across the country as an ambassador for a wonderfully exotic horticultural practice. Presumably, Yuji was heavily dependent on the kind assistance of others to find his way across the sprawling expanse of America. Certainly, he made new friends and attracted supporters wherever he went. Still, what an enormous degree of personal courage it must have taken for him to do it.

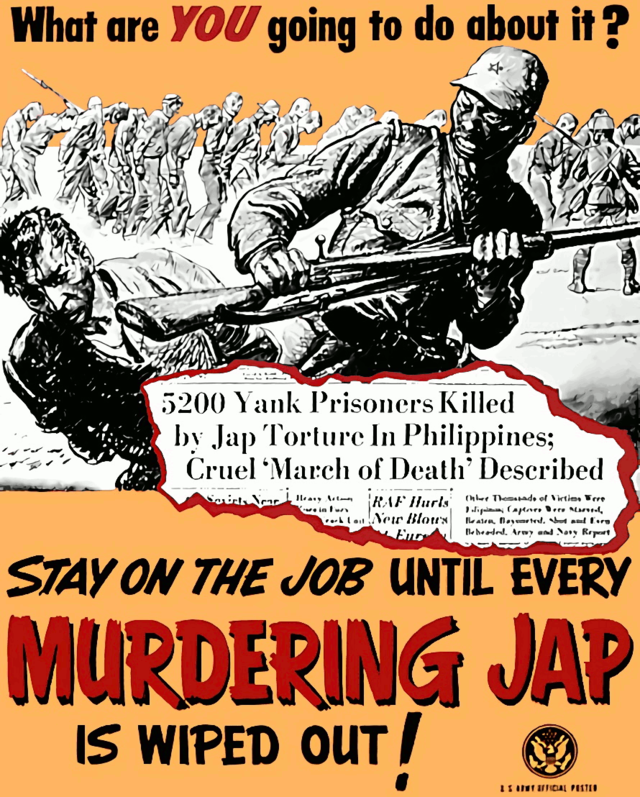

History teaches that part of any war effort is dehumanizing the enemy. In order to countenance the horrific acts of violence war entails, it is necessary to believe that your side and what you are fighting for is good and the people you are fighting and what they represent are bad. As World War II raged in the first half of the 1940s, the United States very much conceived of Japan as the enemy and Japanese people were led to view Americans the same way. The Japanese were portrayed in America as merciless, bloodthirsty and, most of all, sneaky (Remember Pearl Harbor!) They were the enemy and it was necessary to hate them so that we could prevail.

The images above were part of the anti-Japanese propaganda campaign conducted in the United States during World War II.

Reconciling previously encouraged animosities is to be hoped for at war’s end, but not so simply achieved. People are people, and emotions once excited to the highest pitch are not easily brought back under control. There was in the post-war United States lingering prejudice against Japanese people. I know this as a student of American history, but also from personal experience. Even in the 1990s as I was first learning about bonsai I would sometimes hear comments that reflected an ignorant conception of Japanese people and culture, rooted, at least in part, way back in the old wartime stereotypes. I think now the effect has been greatly diminished with the passage of so many years. In the late 1950s, however, it must have still been prevalent.

What was it like for Yuji Yoshimura as a Japanese man to travel across the United States in the 1950s? On one hand, he was invited here because he was an authority on a certain horticultural practice that had captured the imagination of a small portion of the Western world. He was welcomed and many people treated him as an honored guest, helping him in his mission to spread knowledge and appreciation of bonsai. On the other hand, he was a stranger in a strange land, noticeably different and easily identifiable as someone who might have been among the enemy not so long ago. Bonsai was largely unknown in this country then, and not something immediately appealing to everyone. Surely, even as he felt welcoming interest in certain places, he must have at other times felt completely isolated and alone. He was so far away from his home — both physically and culturally — and separated from his family, friends and colleagues.

Yet when his fellowship came to an end after the autumn session of classes at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Yuji did not return home. Instead, he took up residence in Tarrytown, New York, just north of New York City.

So began the next remarkable phase in Yuji Yoshimura's life. He would later explain that he liked America and found Americans to be friendly, and perhaps that was reason enough for his remaining. Still, it's difficult to look at the course of his career and not conclude that Yuji was driven by some great ambition. The general promotion of bonsai was clearly important to him because he dedicated his life to it. But he might just as well have promoted bonsai from back home in Japan as all his contemporaries chose to do. His path would have been easier. Just as when he was the one bonsai professional who saw opportunity in the foreigners who flooded Japan at the war's end and capitalized on it, Yuji came to America and saw opportunity in the big, vibrant country that was positioned to lead the world. Whatever conflicting emotions he may have had, Yuji decided the future for him was in the United States.

At the end of 1959 Yuji established the Yoshimura Bonsai Company in partnership with a woman who had been one of his students. After that he set up the Japan Bonsai Trading Company in Tokyo. In 1962 he began teaching bonsai at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx and soon after oversaw the creation of the Bonsai Society of Greater New York. That group organized shows at the botanical garden and began producing a quarterly magazine called the Bonsai Bulletin, and Yuji was the driver behind all of it. He established a bonsai beach-head on the East Coast of the United States, reaching out from there to areas nearby and places far off. Yuji traveled to Australia, Hawaii and Hong Kong to spread the good word of bonsai. He made numerous annual trips across the country to California and encouraged bonsai clubs there to organize. By the end of the 1960s the art of bonsai was finding traction all over the world and especially in America. Yuji Yoshimura was a primary agent of the spreading bonsai phenomenon.

In the mid-1960s Yuji's wife and two daughters came to live with him in New York. After five years, however, Mrs. Yoshimura returned to Japan taking the couples' youngest daughter with her. The older daughter remained in America. Although Yuji felt at home in the United States, his wife never did. The family never reunited.

In the early 1970s Yuji moved a short distance from Tarrytown to Briarcliff Manor, New York. He renamed his business the Yoshimura School of Bonsai. Over time Yuji did less importing, focusing ever more exclusively on teaching. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s and into the 1990s he continued to travel the country making presentations to an ever increasing number of bonsai clubs. In time there were larger gatherings like conventions and symposiums at which Yuji would be the star attraction. Everywhere he went he was seen as a supreme authority, a genuine Japanese bonsai master who was readily available in the United States. Over that same span of years, Yuji conducted instruction at his Briarcliff Manor studio and nursery, which was also his home. Countless numbers of students studied there or took classes with him in the various places he visited. Most of the first generation of American bonsai teachers on the East Coast started out as students of Yuji's, including Jerry Stowell, Chase Rosade, Doris Froning, Marion Gyllenswan and William Valavanis.

In the three and a half decades he lived in the United States, Yuji Yoshimura did as much as anyone to shape the course of American bonsai. He lectured, critiqued, instructed, demonstrated, advised, consulted, wrote and published, always investing himself fully, dedicated to the goal of spreading bonsai knowledge and appreciation. Even a suggestion from Yuji could produce great effect. Such was the case when he was doing a demonstration at the US National Arboretum in Washington, DC in 1973 and took the opportunity to speak to his old friend Dr. Creech, who was at that time director of the arboretum. Yuji shared an idea for a place to which American bonsai hobbyists could give their treasures knowing that the trees would be cared for and viewed by visitors for years to come. That vision eventually led to the creation of the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum, the first public bonsai museum in the world.

In 1993 and 1994, when I set out to become Yuji Yoshimura's student, I did not know all the information that is summarized here. I only knew that there were two primary founts of bonsai knowledge in the United States — one was John Naka in California and the other was Yuji Yoshimura in New York. Yuji was the more accessible to me because I lived in the Eastern United States and knew several people who had a history with him. When I saw Yuji do his demonstration at the 1993 World Bonsai Convention, the die was cast. I knew I had to make connection with that giant of a little old man on the stage.