Twists and Turns in the Life of a Corkscrewed Juniper

When I started out in bonsai I participated in a few workshops to get some hands-on experience with respected professionals. As it happened, the first workshop I ever took was in Charlotte, NC, with visiting guest artist Yuji Yoshimura. Mr. Yoshimura was a seminal figure in 20th century bonsai and would ultimately play a key role in shaping my bonsai career. There will be much more to say about him in future Journal entries.

The tree I brought to the workshop was one of the original bonsai donated to the Arboretum at the end of 1992. That donation from the Staples family of Butner, NC, was the beginning of bonsai at the North Carolina Arboretum, so this particular specimen goes all the way back to the genesis of our collection.

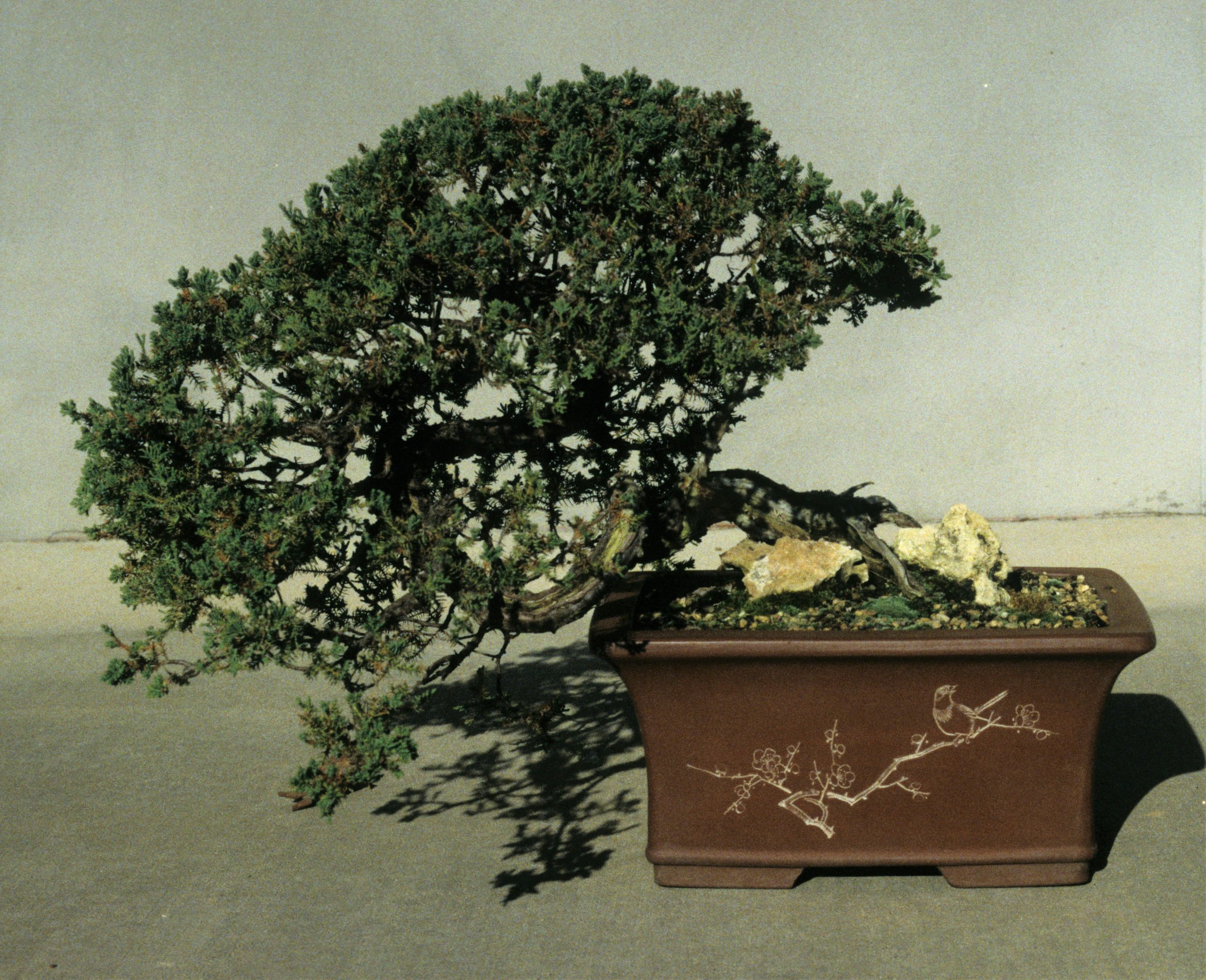

The plant is a procumbens juniper (Juniperus chinensis v. procumbens) and it looked like this when we received it:

1993

Like all the other bonsai we received in that donation, the initial treatment given this juniper consisted of a cleaning, a light trim and a repotting. When I brought the tree to the workshop in spring of 1994 it looked like this:

1994

This workshop was about more than learning bonsai styling; for me it was also about learning how bonsai workshops operate. There were ten people in the class and the time allotted for the session was three hours. The skill level of the attendees was varied and we all supplied our own plants for the workshop, so the size and quality of the material to be worked on was wide ranging. Mr. Yoshimura was more than seventy years old at the time. He made a point of trying to give all the attendees a fair amount of individual attention, but in the end there simply wasn’t enough time to do all the work on all the trees.

As hardly more than a novice I was obliged to wait patiently for the old master to work his way around the room. I didn’t know enough to do much without his telling me what to do, and after all, the purpose of taking the workshop was to learn from Mr. Yoshimura. When I brought the juniper back home to the Arboretum, it looked like this:

1994

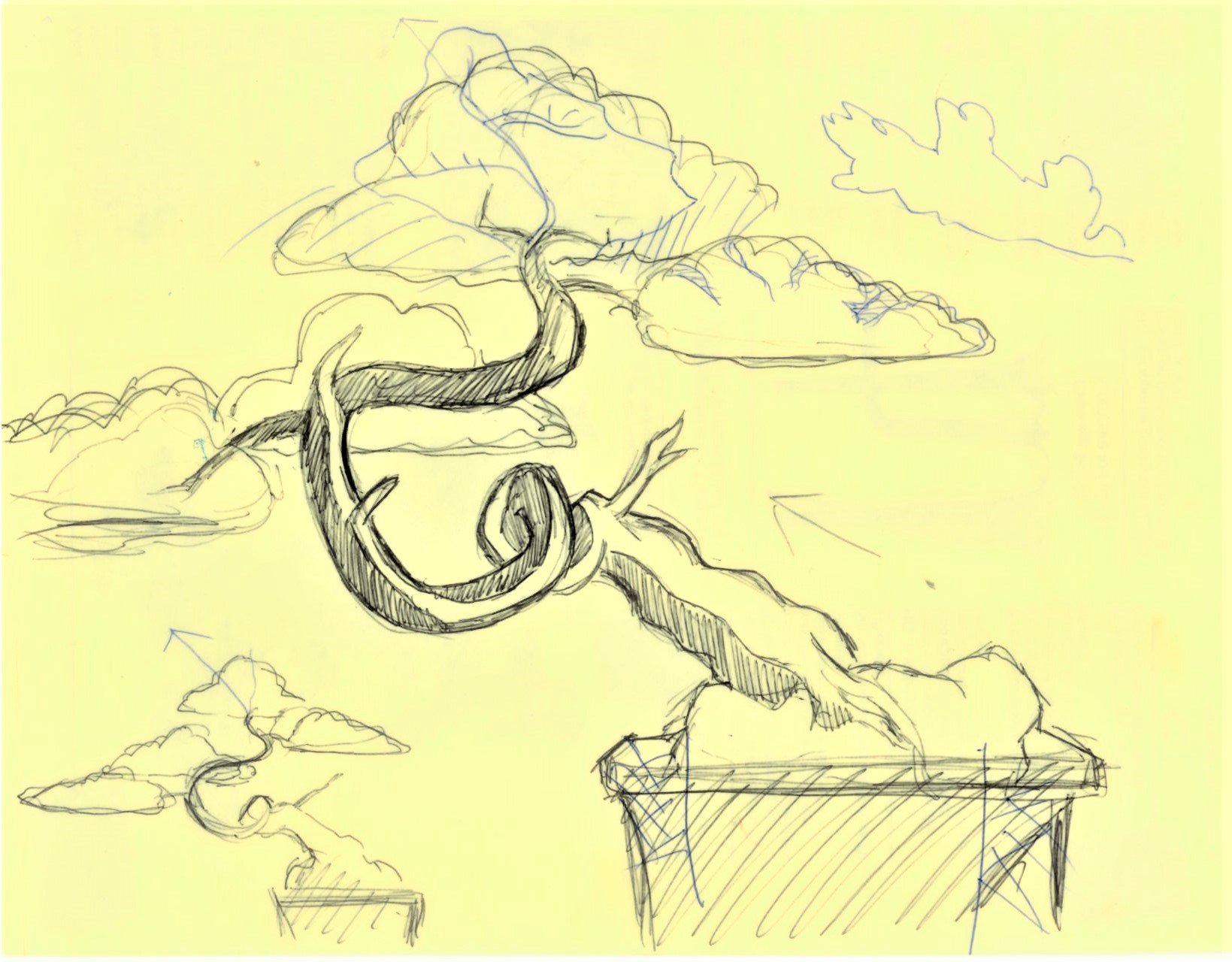

If you are unfamiliar with the bonsai process, and perhaps even if you are familiar, the end result of the workshop session for this specimen might not look very impressive. But considering the limitations of the format, compounded by my own inexperience, it is not surprising the juniper came out looking the way it did. The plant wasn’t the only thing being worked on, however. Mr. Yoshimura, although he didn’t know me personally, knew that I was charged with taking care of a new bonsai collection at a new public garden. That was of particular interest to him. He made a point of giving me a little extra attention at the very end of the class, explaining in detail his vision for the future development of the juniper. Based on his description, I made a quick sketch of what the bonsai might look like someday and showed it to him. This is a copy of that sketch:

1994

I made the sketch using a black ballpoint pen and Mr. Yoshimura indicated his corrections to the design using a blue pen. There were three main points he wanted to reinforce: The directional movement of the uppermost part of the tree should echo the directional movement of the tree’s lower portion; the masses of foliage should be more irregular in their outline than the way I had drawn them; the pot for the tree should be tight and narrow in shape in order to highlight the dramatic movement of the trunk.

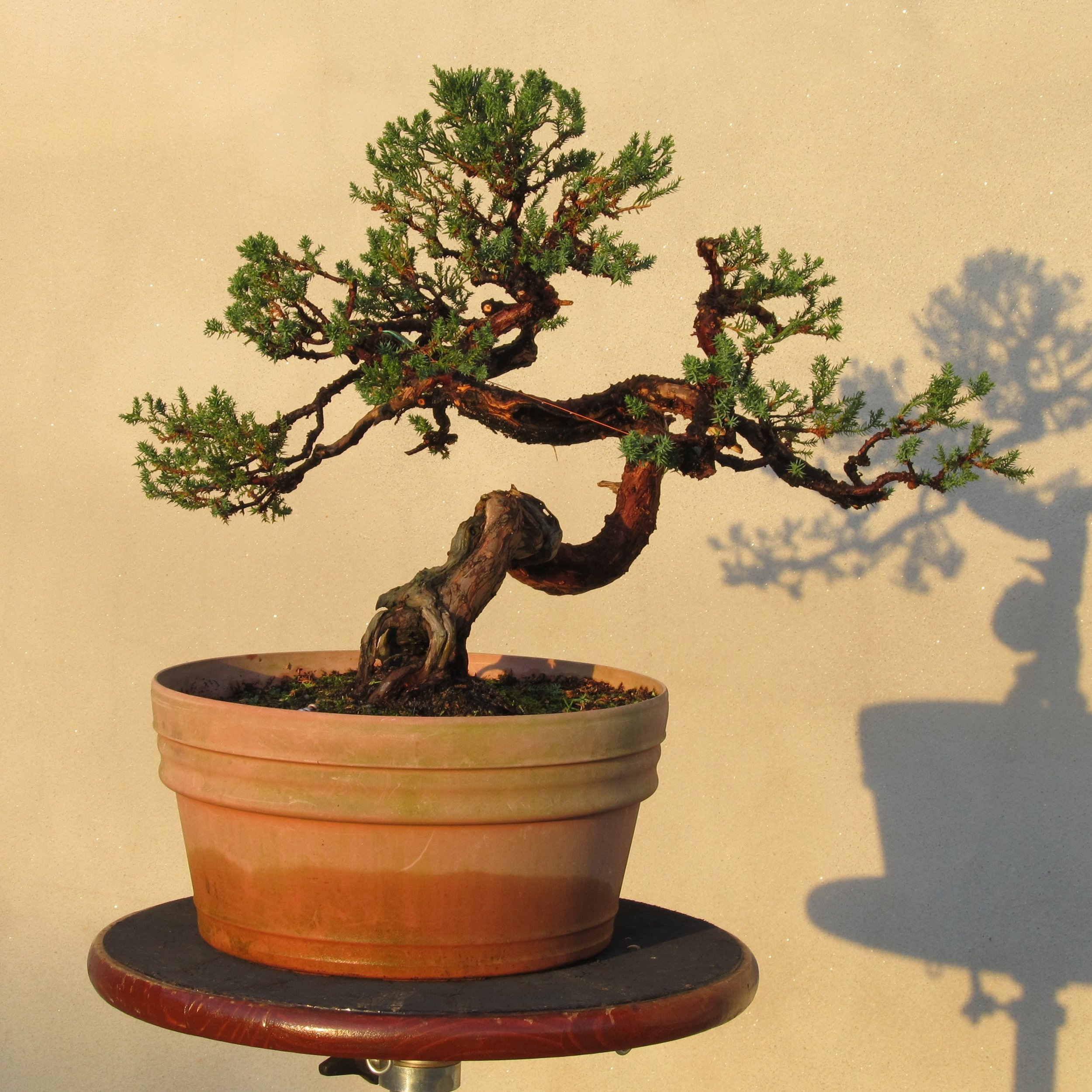

I went to work on the juniper sometime not long after, trying to bring into being the design Mr. Yoshimura had outlined. All the tree’s branches were wired and shaped. The photograph below shows the tree tilted upward from the angle at which it was planted, to make it a more upright-growing bonsai rather than a recumbent form:

1994

Having made a connection with a famous bonsai artist, I was intent on staying in touch with Mr. Yoshimura. I sent him a letter thanking him for his teaching and included the above photograph, in addition to a more finished-looking sketch of his design idea:

1994

The primary point Mr. Yoshimura made to me during the workshop was the importance of first recognizing the best feature of any given bonsai subject and then developing a design to best promote that feature. He impressed upon me that with this particular juniper the best feature it offered was the corkscrewed nature of the trunk line. It is unusual, but rather than seeing that half-dead, raggedy, looping line as ungainly or flawed, Mr. Yoshimura embraced it as distinctive. He therefore chose a presentation of the juniper that placed its most distinctive feature front and center. At the workshop Mr. Yoshimura spent much of his time with me making this point by presenting the tree in various positions and asking me what I thought of each look.

The idea of identifying what is most appealing about a tree and making that feature more prominent through presentation is fundamental to good bonsai design. Other teachers have taught this, but I learned it that day from Mr. Yoshimura, on this juniper specimen.

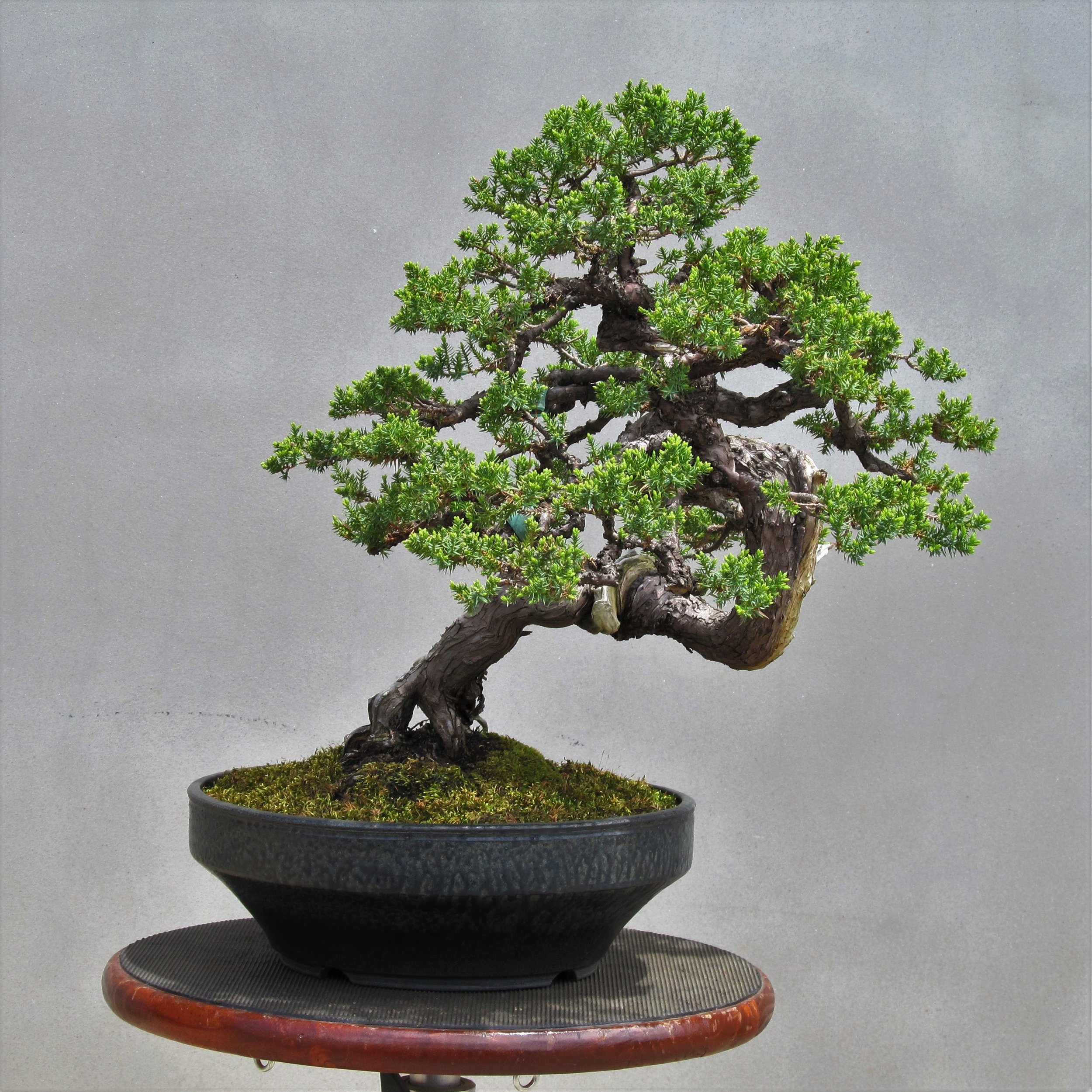

After a few years work the juniper began looking more like what Mr. Yoshimura had envisioned. In the photograph below, note that the bonsai is planted in a container more in line with what he had described in his adjustment to my first sketch:

1997

Somewhere along the way it became too difficult to maintain the tree in that very tight container. The arrangement was physically top heavy, and the limited amount of growing medium was prone to drying out too quickly. I would not care to argue about whether the look of the dramatic trunk line was or wasn’t accentuated by the narrow pot, but regardless, as a matter of practicality the juniper needed a bigger container. As the next photograph shows, the tree was subsequently planted in a slightly larger pot of similar design:

2002

Can you spot the difference in the bonsai between the image above and the next image, made the following year?

2003

The 2003 image shows the tree potted in a more upright position. This was done to counterbalance the tendency of the tree to slowly list to the left side, due to the weight of the foliage mass and how that mass is positioned atop the serpentine trunk. There is visual tension created by the narrow, twisting trunk and the wide, spreading crown, but keeping such an arrangement in a state of physical balance is challenging.

The next photograph presents the juniper on display at the opening of the bonsai garden in October of 2005:

2005

How fitting that this particular bonsai, from the original donation that started our bonsai enterprise, should have been among the first specimens shown in the new garden! It is possible to see the juniper as it appeared then as the full realization of the design idea Mr. Yoshimura had described to me at the workshop eleven years earlier. More accurately, the juniper as it was in the 2005 image represents the realization of Mr. Yoshimura’s design idea as I understood it. If Mr. Yoshimura himself had grown and guided the tree all that time the result would not have been the same. One expects Mr. Yoshimura’s juniper would have been better, but it certainly would have been different.

There is a tendency to think of bonsai as static and unchanging, as if they were statues. They are sculptural in their effect, but bonsai are living sculptures, and that means they are growing and changing all the time. Ideally they grow better and change for the best. In reality, they have their ups and downs, their good years and bad years. Sometimes it seems the trees get worn out — as plants — by all the limitations placed on them over the years of discipline required to make them bonsai. I think that’s what happened with this juniper just a few years after the previous image was made:

2009

Clearly, the 2009 photograph shows a bonsai in serious decline. In response to this emergency, the juniper was removed from the bonsai pot and planted in a large nursery container. It was fertilized generously and allowed to grow without restriction, with no concern given to any purpose but saving the plant’s life and recovering its health. The juniper responded wonderfully, with great renewed vigor:

2011

It is amazing to consider the previous two images show the same plant, only two years apart! I might at this point have begun restructuring the juniper to be a bonsai again, but I did not. Lack of time was probably the reason for delay. It is much easier to let a plant grow freely than it is to maintain it as a bonsai, and procrastination can be excused by the health benefit the plant enjoys while on “vacation”. However, a bonsai can be allowed such freedom of growth for only so long before elements of its design detail are irrevocably lost. When the juniper reached the state of overgrowth depicted in the next image, it was time to act:

2014

The juniper received a drastic pruning immediately after the previous image was made. The objective was not to remake it as a bonsai in one session, which would have been too much stress all at once, but to broadly “rough-out” the form the tree had before it fell into decline. The four images in the following gallery show a 360-degree view of the specimen after this work was completed. Note that the juniper had fallen over to the left once again under the weight of the vigorous regrowth, and needed to be propped up to assume its correct bonsai posture for the photos (click on any image for larger view):

Recovery work continued the following year. The next series of images show the tree after further refinement had been accomplished in the crown, and its posture had been corrected during repotting (click on any image for larger view):

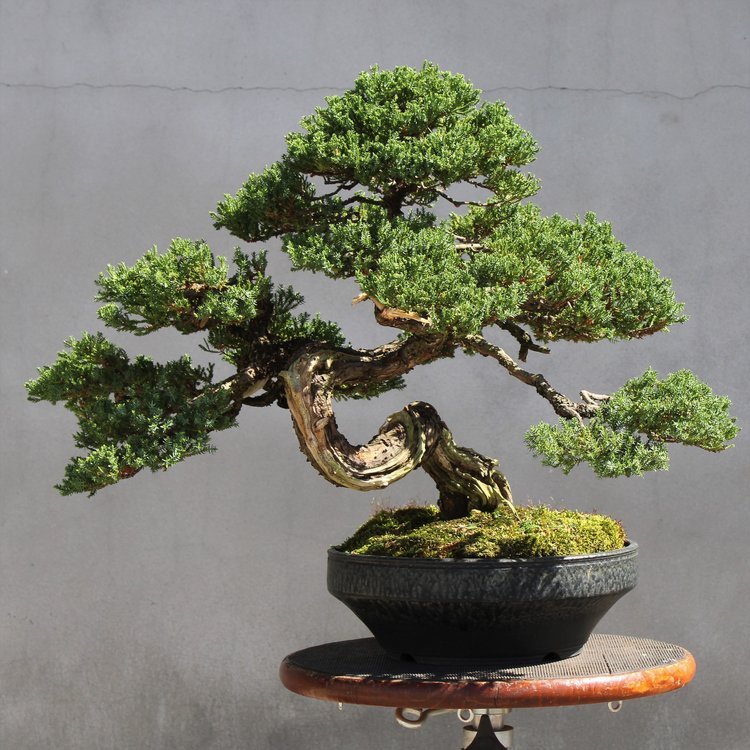

The following year brought further refinement of the branching and foliage masses, as well as another repotting. This time the tree was planted in a handsome new bonsai container, the work of Mississippian potter Byron Myrick. Seven years after being at death’s door this juniper was back to being presentable as a bonsai (click on any image for larger view):

Back on display in the bonsai garden:

2016

2017

2020

The juniper was not displayed in 2021 or 2022. During that time it received minimal pruning and once again became full and overgrown, although not nearly to the degree it did during its recovery period a few years earlier. Recently I spent a day going through the tree’s crown and once more redefining the branching and foliage masses. It is due for another repotting this year and then the corkscrewed juniper will be ready once more for display in the garden (click on any image for larger view):

This specimen has changed considerably in its thirty-year career as an Arboretum bonsai. The changes were drastic sometimes, although more subtle in recent years. Throughout, the basic design idea imparted by Mr. Yoshimura in the 1994 workshop has been largely maintained. In certain particulars, notably the construction of the crown and the character of the container, the bonsai has a different look. Such change is normal and inevitable over time due to the living, growing nature of any tree. The evolving thought process and skill level of the person responsible for management of the living, growing tree comes into play as well. But as regards the element Mr. Yoshimura identified as the most compelling feature of this bonsai — the coiling trunk line — it is still front and center, just as he positioned it.

Not everywhere can you see a series of a dozen images illustrating a thirty-year period of stylistic development in a single bonsai specimen, but here at the Curator’s Journal you can (click on any image for larger view):