Up on Slingshot Ridge

It is sometimes said, at least among people who talk about such things, that American hop-hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana) is the upland version of American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana). The two tree species are of different genera although both are in the birch family (Betulaceae). Hop-hornbeam leaves look similar to hornbeam leaves and both look similar to birch leaves. Hop-hornbeam and hornbeam both produce dense, hard wood and as a result both are sometimes confusingly called by the same common name: "ironwood." Both species are understory trees, typically twenty to thirty feet tall at maturity although capable of being larger. But whereas American hornbeam is often found growing in moist soil near streams and rivers, American hop-hornbeam is usually found in dry, rocky forests and on sharp-draining slopes. In truth, neither is so clear cut in its preferences and there is overlap in their habitats. To see the two species side by side, what really sets them apart is the character of their bark. American hornbeam has smooth, light gray bark, although older trees will sometimes exhibit fissures in the bark on the lower portions of their trunks. American hop-hornbeam, on the other hand, starts out smooth-barked, but as the tree begins to mature the bark becomes shaggy in appearance. Older trees often feature shredding bark, peeling off in paper-thin strips, colored in shades of brown and gray and appealing in visual effect.

Fruit of hop-hornbeam, thought to resemble hops and hence the name hop-hornbeam.

Hop-hornbeam planted in the Arboretum landscape, near the amphitheater.

In bonsai, American hornbeam is more commonly used than hop-hornbeam. The reason for this is somewhat mysterious, given both species work equally well for the purpose. This disparity is reflected in the Arboretum's bonsai collection, where we have numerous American hornbeam specimens but only one hop-hornbeam. The one hop-hornbeam specimen we have is substantial, however, and we've had it for a long time.

In the early days of the Carolina Bonsai Expo we operated on a shoestring budget. Most of the money the Arboretum spent went to table rentals and paying the guest artist. But various individuals from the participating clubs who generously volunteered their services helped fill out the show with free bonsai programs, enlivening the event with educational content. Two such willing helpers were Ken Duncan and John Geanangel. They were both members of the Bonsai Club of South Carolina, based in Columbia, an organization that was later succeeded by the Black Creek Study Group. As members of one organization or the other, those two individuals participated in all twenty-four years of the Carolina Bonsai Expo. At the 1997 Expo John and Ken did a forest planting on a large rock as an educational demonstration, using American hop-hornbeams they had collected from the woods near the Saluda River. This is what they put together:

As the photo shows, John and Ken did good work! The hop-hornbeams were not very old, but they had good natural character in their trunks and a reasonable amount of branching. There were trees of varying sizes and they were thoughtfully arranged in keeping with standard Neo-classical bonsai forest planting methodology. In addition to the hop-hornbeam trees, there was an understory planting of dwarf azaleas (Rhododendron 'Chinzan') and a few bits of a native perennial called flowering bluet (Houstonia caerulea). The rock was big, measuring twenty-two inches from front to back and thirty-six inches in length. It was a heavy thing, purchased at a stone yard in South Carolina, but originally collected in Pennsylvania.

In a happy surprise, John and Ken offered the new planting as a donation to the Arboretum's collection, and we gratefully accepted.

The next photo we have of this planting dates to October of 2005, when the hop-hornbeam forest was featured in the grand opening of the bonsai garden:

The hop-hornbeam forest has been on display in the garden most years since that venue opened. It is a popular piece in our collection for a number of reasons — it is large in scale; a forest planted on a rock; colorful during springtime flowering and again during autumn leaf change; and features a native tree species with a strange name that many folks have never heard of before.

Here is a comparison of the planting in two images, showing branch development that occurred on the hop-hornbeam trees over a ten-year span (click on either image for full view):

2009 was a good year for this bonsai, as evidenced by the number of times it was photographed over the course of the growing season (click on any image for full view):

This image from 2013 looks pretty with the azaleas in full bloom, but a closer inspection reveals early signs of a problem that would worsen over time:

Compare the density of the very top of the tallest tree with the tops of the other trees in the planting. All of the other trees are more densely branched and carry more foliage than the tallest tree, and that tallest tree is meant to be the main one in the grouping. In bonsai parlance that tree is referred to as the number one tree. It is not desirable to have the number one tree in your forest look weak, especially if all the other trees in the forest look strong. There is no image showing how that main tree continued to decline in the next few years, because as it did I stopped taking pictures. Within three years of when the photo above was made, the main tree was half dead and the hop-hornbeam planting was off display.

The 2016 Carolina Bonsai Expo offered an opportunity to remake the forest and do it as a public demonstration. After watching John and Ken do the original planting at the 1997 Expo and seeing how much fun they had working as a duo on stage, I asked if they would consider letting me join them in future demonstrations. At most of the Expos after that the three of us did educational presentations as a trio, and over the course of the next two decades, we did some pretty nice work together. Remaking the hop-hornbeam forest on the big rock with John and Ken at the Expo, nineteen years after they originally created it, was a satisfying experience.

A lot happened to the forest planting during the onstage makeover. For one thing, the forest received a new number one tree, courtesy of Ken. He happened to have a good-sized hop-hornbeam in a training pot among his personal collection and he offered it as a replacement. The old forest was disassembled and then a select number of trees from it were used to create a new forest around the new main tree. Instead of following the prescribed method of arranging a bonsai forest planting, the placement of the trees in this forest was done according to feeling. That is to say, the trees were arranged in the way that “felt” best, based on what we were seeing as we put it together. The same big, flat, heavy rock was used as the foundation of the planting, but the rock was flipped upside-down and what had been the front side of it became the rear. The arrangement of the forest trees, which used to feature right-to-left visual movement, now was organized to be read from left to right. The understory of the forest was once again planted with the same azaleas and bluets, so that aspect of the composition remained essentially the same.

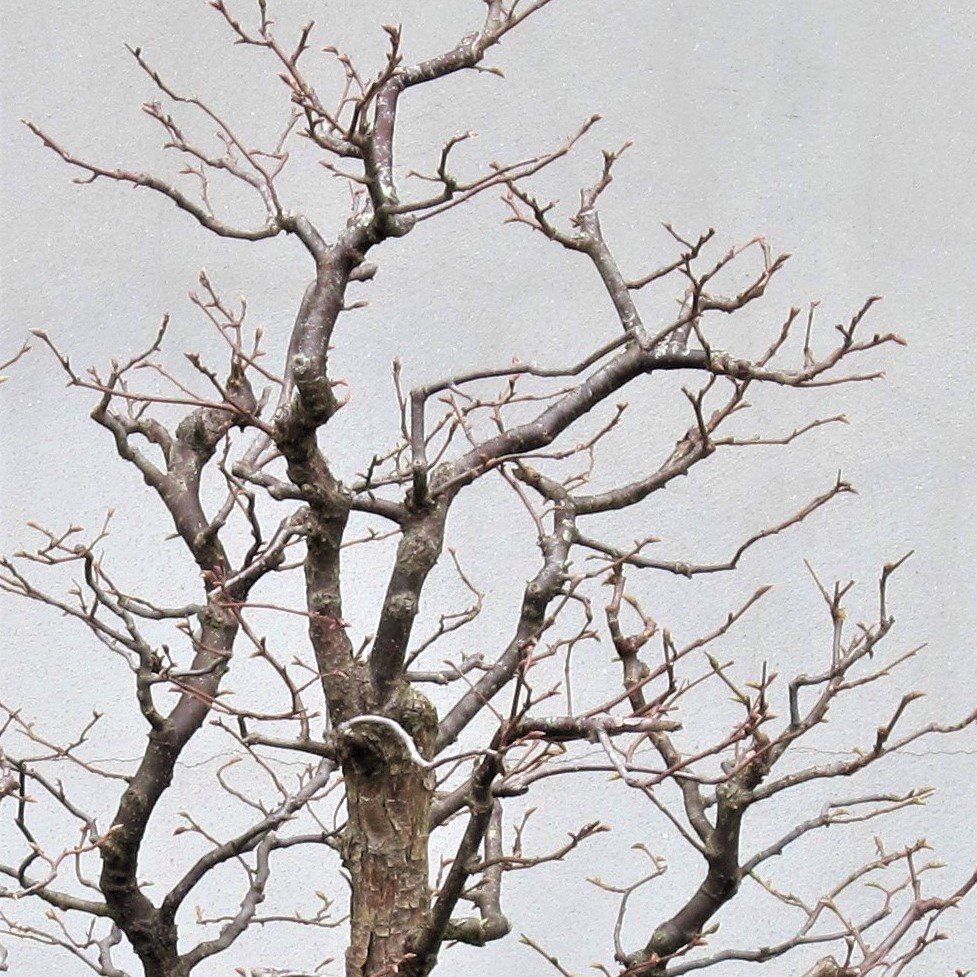

The demonstration in which the hop-hornbeam forest was remade took place in October of 2016 and in spring of 2018 the planting was back out on display in the bonsai garden. It enjoyed a healthy year and went through all the usual seasonal variations without missing a beat:

The new version of the hop-hornbeam forest on the big rock was given a poetic name: Up on Slingshot Ridge. The name came from a particular feature of the new number one tree. In the upper third of that tree there is a pronounced fork in the trunk line:

If you are not trained in a certain bonsai aesthetic, you might think there is nothing untoward about that forked section of the tree. It looks completely tree-like. Many bonsai people, however, when looking at that same section would identify it as a problem, a design flaw that wants correcting. It is thought that such a forked trunk line is ungainly, even ugly, because the angle of the crotch is too closed and narrow, and the caliber of the two diverging lines is too similar. It is usually referenced with the derisive observation that it looks like a slingshot. When Ken gave us the tree to use in the new planting, he said, "This tree is the right size and has good branching, but you'll probably want to cut off one or the other of the branches coming out of that narrow fork." That set me to thinking about it. I had the same reflexive reaction when looking at the top of that tree because it's an ingrained way of thinking about proper bonsai design. It’s the way we are taught to think about it.

I wanted to defy the taboo and leave that forked top intact. John and Ken, being my friends and open-minded about such matters, agreeably went along with the idea. Naming the planting Up on Slingshot Ridge was a covert way to poke some fun at dogmatic thinking, but the name had appeal beyond simply being an inside joke. Slingshot Ridge sounds like a name you might actually come across out in the forest, and it lends the planting a certain colorful identity.

As it happens, diverging from the conventional bonsai aesthetic can lead to more naturalistic bonsai:

2022