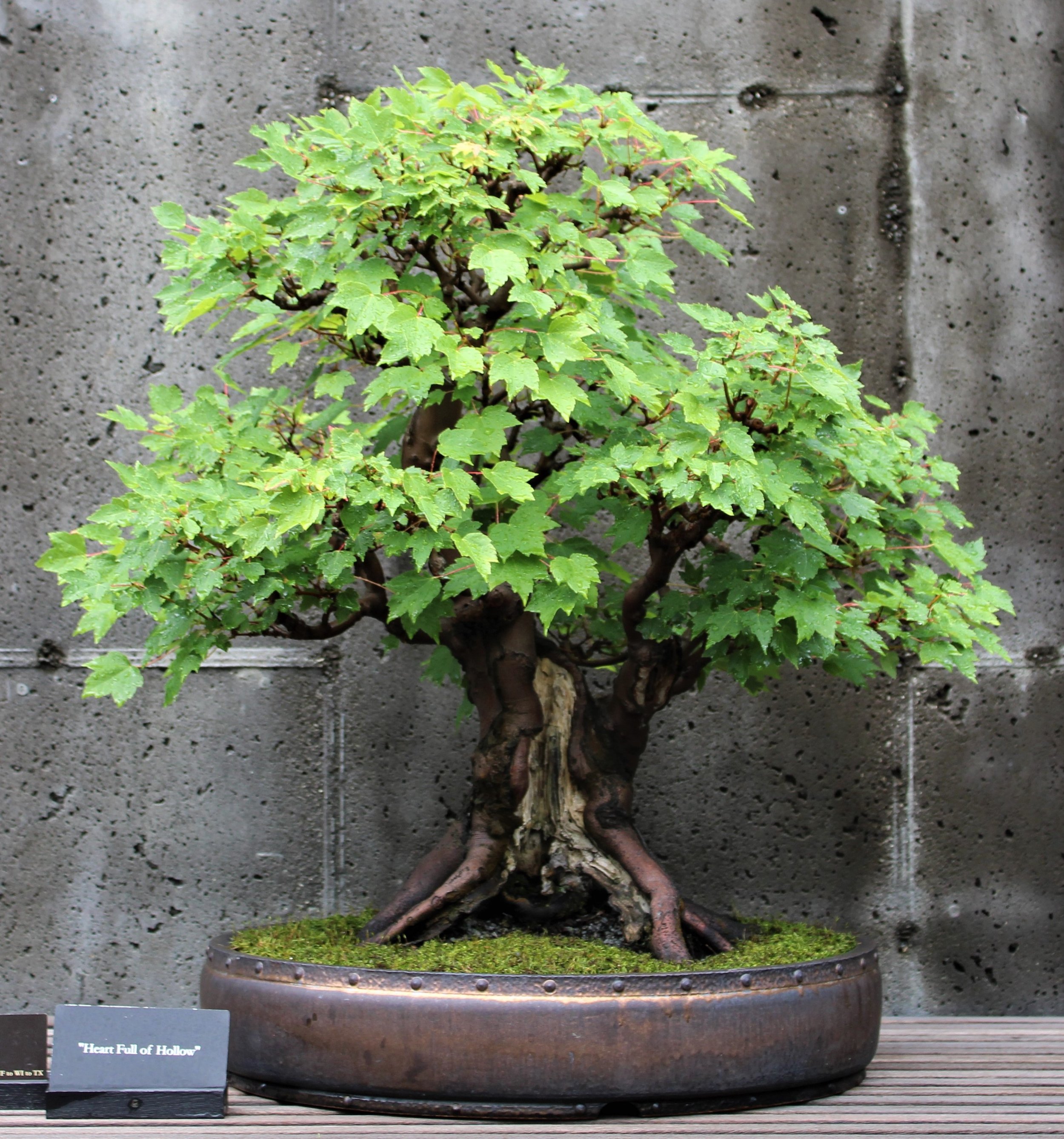

Heart Full of Hollow

Two factors combine to shape all trees: Genetics and Environment.

Genetics, which provides us with the biological blueprint that is the one true birthright of every organism, dictates the species of the tree, its physical traits and capacities. Genetics determines that a red maple (Acer rubrum) is a red maple and not some other type of maple, and not a beech or a pine or any other type of tree. A red maple will have the bark, buds and leaves typical of a red maple, and will produce red maple wood, and will be capable of growing over a hundred feet tall and living for a hundred years or more. This genetic information is hereditary, handed down from a parent tree that was also a red maple. If the red maple in question reproduces, all its offspring will be red maples, as dictated by the genetic information that is passed along.

Environment in this context refers to everything that happens to the tree in the course of its existence. A great many things can happen to a tree, sometimes to the tree's benefit and sometimes to its detriment. How any given tree responds to these events will have impact on that tree's physical appearance. Environment provides the individual circumstances of every tree's life. Each tree has its own unique set of experiences, and this is why no two mature trees could ever be identical in every way. Even if the two trees are both of the same species from the same parent tree, or even if they are clones of the same parent tree with identical genetic information, planted right next to each other, they will vary in some aspect.

The intersection of genetics and environment produced these widely-varying versions of red maple in nature (click on any image for larger view):

The intersection of genetics and environment also produced this red maple bonsai from the Arboretum's collection:

This homegrown bonsai specimen stands out in autumn with foliage the color of a fire truck, a feature attributable to the tree's genetic inheritance as a red maple. It is large, standing just under thirty inches in height, with a diameter of eight inches just above the surface roots. That is big for a bonsai but small for a mature red maple, a consequence of the environmental impact of being cultivated as a bonsai. Aside from its outstanding autumn color and substantial size, this bonsai is distinctive because it exhibits extensive damage to the main body of its trunk. The damage was also a consequence of environmental effect and is so integral to the individual identity of this bonsai specimen that it is acknowledged in the tree's poetic name: Heart Full of Hollow.

Sometime back in the early 2000s a red maple was languishing in the Arboretum's container nursery, intended for landscape use but somehow never finding a home. The tree became pot-bound in its big plastic nursery can, and because it was about six feet tall it was prone to falling over whenever the wind blew. Eventually this unwanted maple was viewed as a nuisance and scheduled for deaccessioning. The tree had some size in the trunk and a well-formed base with good surface roots, so it caught my eye as a possible candidate for being a bonsai. I saved it from the compost pile, cut it down to its lowest branch and transferred it from the nursery to the bonsai area, where it was then neglected a few more years but was no longer prone to falling over. Finally, out of sympathy for its still pot-bound condition and concern at how slowly it was producing callous material to cover the gaping wound left by the trunk chop, I planted the maple in the ground. Here is the first image we have of this specimen, made late in 2008 after the tree had been in the ground a year or two:

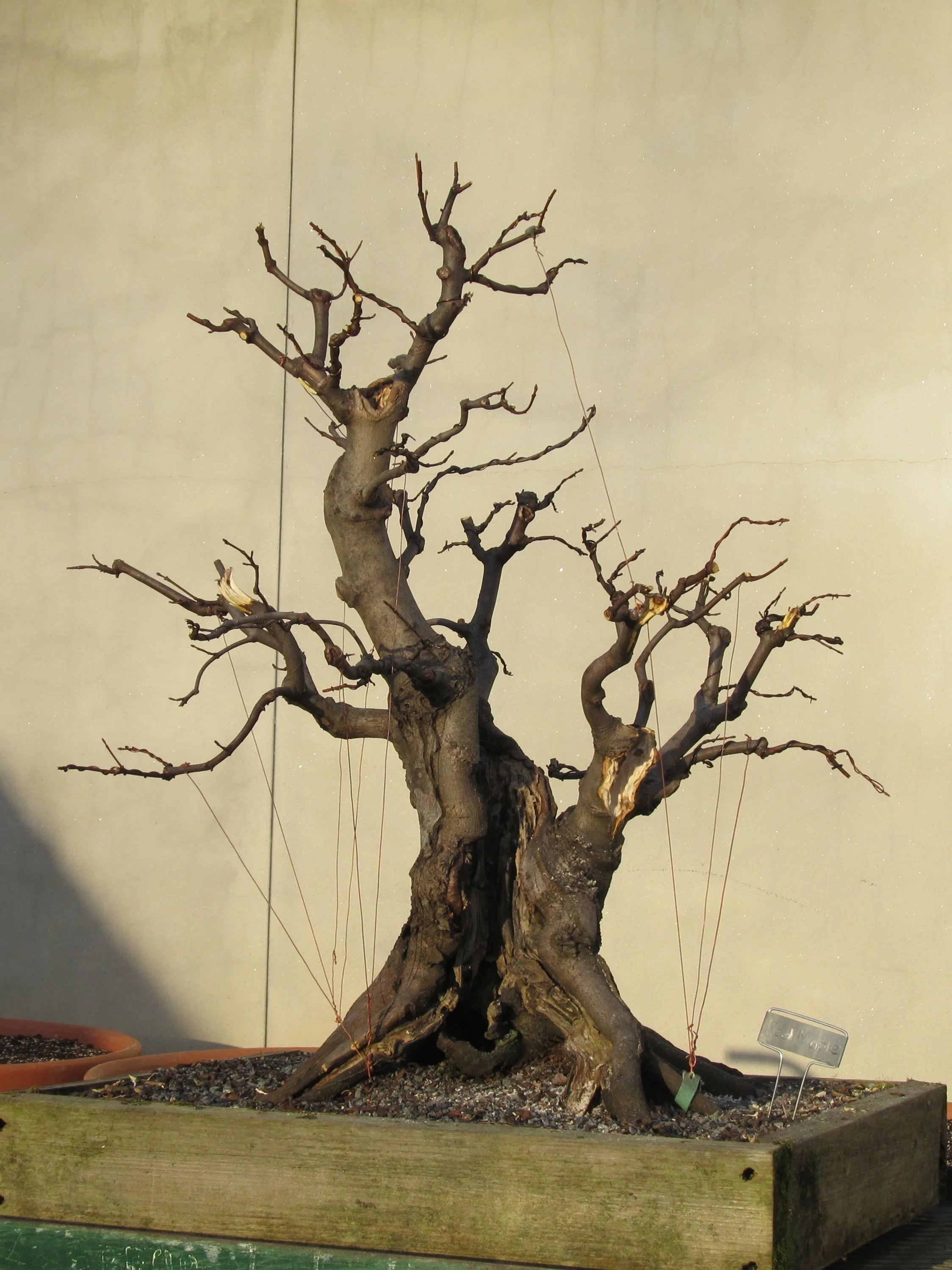

There came a time when I decided I might not live long enough to see the big wound completely cover. Feeling experimental with a sense that there really wasn't much to lose, I chopped the tree again. Here is what it looked like in April of 2009, the nadir of this maple's existence (click on any image for larger view):

Poor tree! But do not despair — this is a red maple we are talking about, and if chopped right down to the ground it would likely grow again from the roots. The capacity to do that is part of its genetic inheritance. Two seasons of more or less undisturbed growth after the severe cutting back produced this result in February of 2011:

Obviously, the tree survived the brutality of being twice chopped, but not without paying a price. Closing in on the above photograph, we can see that the resulting wound proved too large to cover over and the exposed wood began to decay:

In addition to the decay, the exposed wood was attacked by termites that chewed vertical channels in it right down to the soil and then some. My reflexive impulse was immediately to spray the tree with insecticide and kill the pests. Upon closer inspection, however, I could see merit in what the termites were doing. Working with their tiny but powerful jaws, the insects were sculpting the dead wood into a more interesting form, not out of intention but as a result of their genetic impulse to chew wood in a particular pattern. I let them go about their business a little longer, until it seemed their appetites were exceeding the bounds of aesthetic interest. At that point I dug the tree out of the earth and planted it in a very large wooden grow box, where I could eradicate the termites and make certain they did not return. I cleaned up the damaged area but left as much of the termites’ carving as I could. Red maple wood does not hold up particularly well to outdoor exposure, so I burnished the cavity with a small torch, brushed it clean and then treated it with wood hardener. Here is what the result looked like in April of 2011:

In order to encourage the plant as it made the transition from growing in the earth to once more growing in a container, I did not prune it that growing season. Here is what it looked like nearly a year later, in March of 2012:

I spent a few hours sorting through all the new growth, cutting away most of it but retaining all branching I thought might serve my purpose. This next picture was made the same day as the previous one:

This image, made on the first day of November 2013, shows the hollow-trunked red maple sitting on a bench in the hoop house. The sheer gaudiness of it prompted a photograph and provided a foretaste of the brilliant color display this specimen has produced in autumn every year since:

Later that same month, once the leaves dropped, the tree had this appearance:

At this time I decided to transplant it into a smaller grow box in preparation for eventually getting it into an appropriately-sized bonsai container. Just as we carefully work the top of a tree in development, incrementally bringing it into bonsai form, so too we should be simultaneously working the root system step by step. When I transplanted this maple from the ground into a grow box in 2011, I decided to minimize the trauma by not bare-rooting it just yet. But now I felt it was ready. Here is the naked tree, showing a fibrous root system in excellent condition:

Please note that this bare-root transplanting was done in the month of November. The large number of bonsai trees we care for at the Arboretum dictates that we must do some repotting at times that are less than optimal. We have experienced little difficulty doing this, and no problem at all with doing it to red maples. Asheville is in zone 7a so we do get cold. Not Minnesota cold, but teens and single digit and sometimes even below zero degree Fahrenheit cold. The winter of 2013-14 was particularly cold, and this maple went through it after being bare-root repotted in mid-November. The only protection from the elements it received was being located in an unheated hoop house that was covered with white polypropylene. It was up on a bench, too, and not set down on the ground. I am not by any means recommending that other bonsai growers should do this; as previously indicated, we do it out of necessity. The point is, red maples are genetically predisposed to being tough trees.

Here we see the tree at the conclusion of the November 2013 repotting session:

The following images are from 2015, showing the maple as it appeared before its annual springtime pruning and then immediately after. Note the guy wires used to pull branches downward. The third image shows the tree turned slightly clockwise, presenting a new preferred viewing angle, or "front" of the tree (click on any image for larger view):

In 2016 the red maple was transplanted into a bonsai pot, albeit a temporary one. The only container we had large enough to hold the tree was a low-quality tub of a pot that was so inappropriate I purposefully cropped it out of the photographs I made that year (click on any image for larger view):

In 2017 the Arboretum commissioned a custom-made container from North Carolina bonsai potter Ron Lang. The following three images were the first made of this specimen in its new pot (click on any image for larger view):

The red maple bonsai known as Heart Full of Hollow, now at home in its beautiful new container, was chosen to be the logo image for the 2017 Carolina Bonsai Expo. Although the pot is a key component of this specimen’s bonsai identity, I chose to depict the maple without it. The resulting image is of a big old tree with character that happens to be a bonsai but doesn’t need to be seen that way:

Heart Full of Hollow has been displayed in the garden every year since its debut in 2017, and has become a popular favorite with our visitors. The following gallery shows the tree in the cycle of seasonal variation over the years since then (click on any image for larger view):

Red maples have the genetic capacity to respond well to bonsai culture. What happens to any given red maple along the way to becoming a bonsai — neglect, over-assertive pruning, termites, a grower's naturalistic tendencies — will determine what bonsai shape it eventually takes.