How We Started

The love of trees was a prime factor in my seeking employment at The North Carolina Arboretum, back when I was hired in the spring of 1990. Even so, when the Arboretum accepted the unsolicited donation of a bonsai collection two years later and I was offered the job of caring for the little trees, I tried to turn down the assignment. I was happy doing what I was doing at the time, which was most often manual labor out on the Arboretum property. There was a small group of us — four relatively young men — who formed the entire grounds crew, and we spent our days thinning out overgrown sections of the woods, fighting back invasive exotic plants, building the Natural Garden Trail, and roughing out the contours of what would ultimately be known as the National Native Azalea Collection. We were outside most of the time, working on our own with more than four hundred wooded acres to keep us busy, and we rarely saw anyone else all day.

As it happened, another facet of my job description was working as the nursery assistant. The Arboretum had a large production nursery operation back then, featuring woody plant species from all over the temperate world and specializing in southeastern natives. One part of this operation consisted of containerized plants, held in two hoop houses out back of the Production Greenhouse, while another component was a sizable field nursery at an off-site location. The Arboretum's nursery operation produced many thousands of woody plants, covering more than five hundred different taxa, the great majority of which were grown from seed collected out in the field. My immediate supervisor was the nursery manager, Ron Lance, an award-winning naturalist, educator and author. What I lacked in formal schooling I made up for by being Ron's assistant for several years, and I mean that as a statement of fact. I have never known anyone with a broader knowledge of the natural sciences than Ron Lance and I was fortunate to have the opportunity to learn from him. Taken in its entirety, my first few years at the Arboretum were a priceless experiential education in ecology, botany and horticulture, in addition to being an invigorating outdoor adventure. I was quite satisfied with the arrangement. The idea that I should give up any of that so I could spend my time dithering around with strange, stunted plants stuffed into fancy little pots was not enticing.

That initial unenthusiastic reaction to bonsai represents a rare anomaly among folks in my line of work. All the other people I've met in bonsai, whether professionals, long-term hobbyists or eager newcomers, were strongly attracted to the art when they first encountered it. These people came across bonsai one way or another and were immediately drawn to it. In my case, bonsai came to me and I tried to push it away.

Part of the reason for my reluctance, beyond the fact that I liked what I was already doing at the Arboretum, was a lack of any real understanding. I had never before seen bonsai except in photographs, and the strangely miniaturized trees were always depicted as artifacts belonging to a foreign culture. Bonsai involves taking trees out of their natural condition, keeping them unnaturally small and confined in pots, and as a practice it has no roots in Western culture. For me it all added up to a conception of bonsai as some oddity from another world. I loved trees, yes, but I loved them as natural entities. Big, wild and free, trees in my imagination are symbols of individuality, each shaped by the rigors of life in nature. The idea of keeping trees perpetually containerized, dwarfed, and clipped into manicured triangle shapes was viscerally disagreeable.

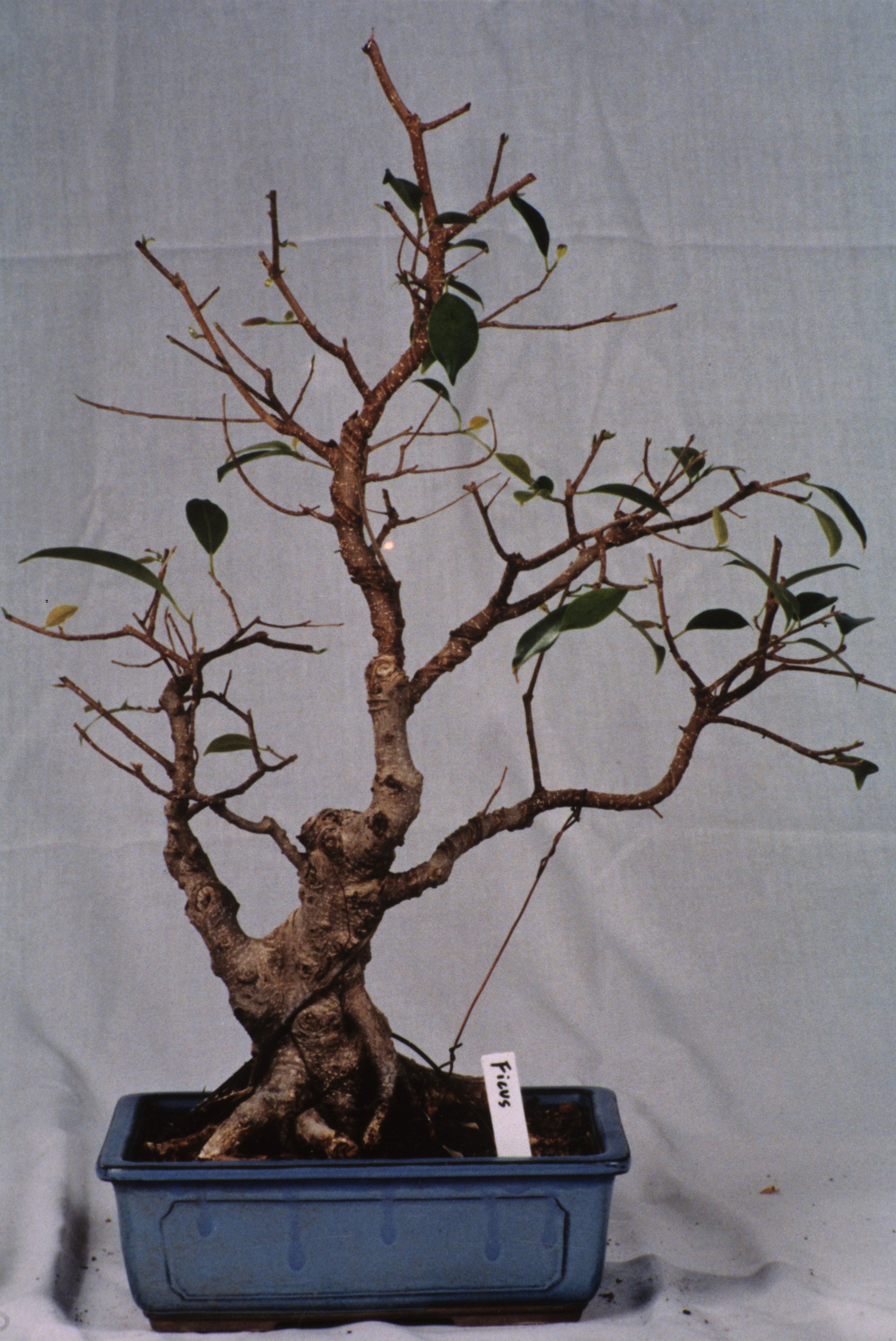

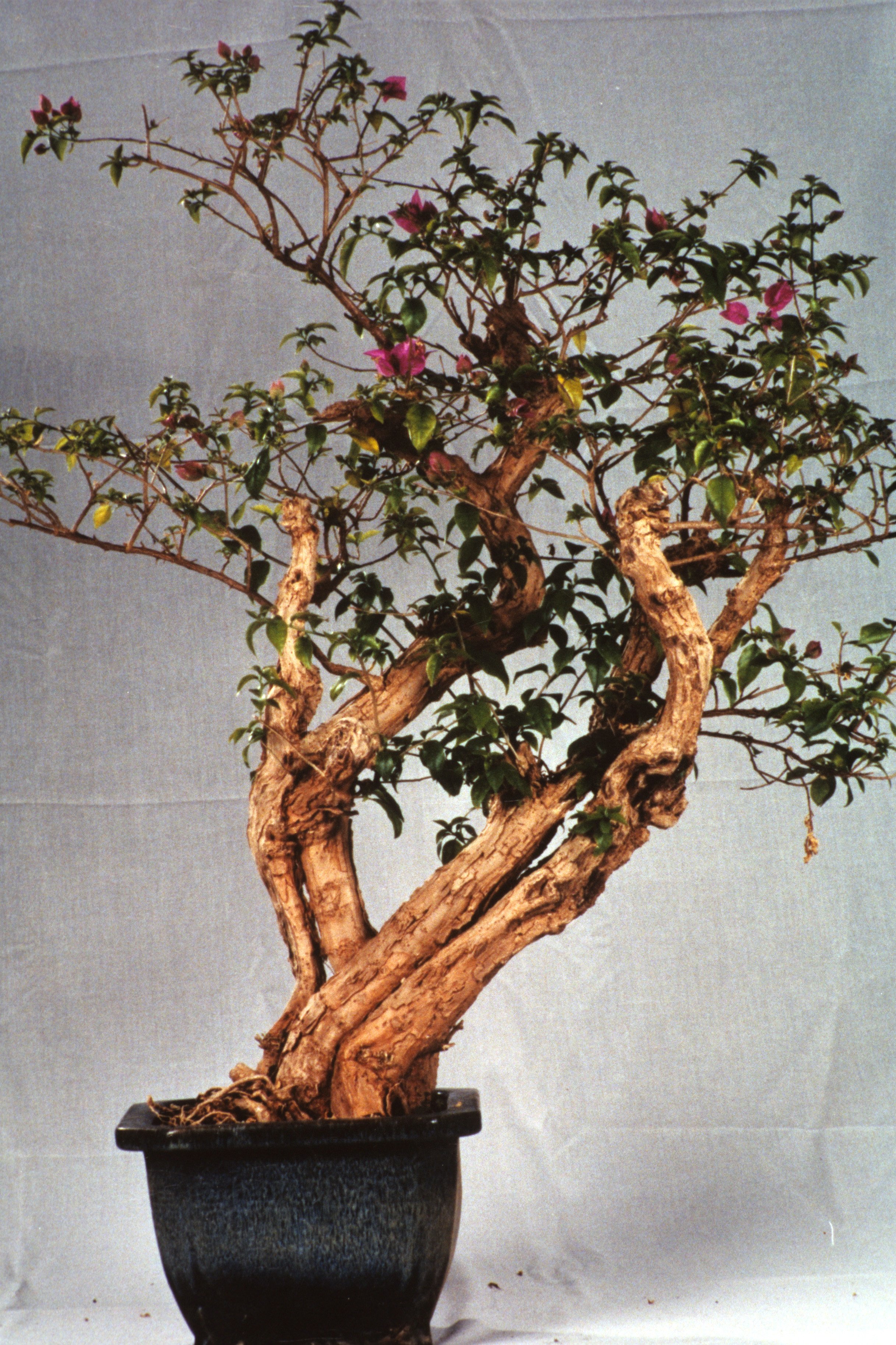

It did not help that the first bonsai I ever saw in-person were those gifted to the Arboretum in the initial donation, the ones I was being asked to care for. That bonsai collection had previously been the pride and joy of Mrs. Cora Staples, of Butner, North Carolina. When Mrs. Staples was diagnosed with a terminal illness, her family began searching for a place where her valuable little trees could go. The Arboretum had been serendipitously alerted to the possibility of receiving Mrs. Staples’ collection in donation, and after some institutional deliberation it was decided we should give bonsai a try. Negotiations ensued and an agreement was reached. Mrs. Staples lived for more than a year after the Arboretum agreed to accept her bonsai collection, but while she was alive she could not bear the thought of her trees being taken away. The problem was that she could no longer take care of them herself and no one else in her family knew how. Mrs. Staples gradually declined and so did her once proud collection. By the time the Staples bonsai collection finally arrived at the Arboretum, it was badly compromised. The plants were overgrown and grossly unkempt, with many infested by insects and harboring disease. They were not the best representatives of bonsai art.

What follows is a gallery of images showing a few of the bonsai specimens received by the Arboretum in that initial donation. The collection arrived in November of 1992 and these photographs were taken in March of 1993. By then the bonsai we inherited had been cleaned up considerably (click on any image to see larger view):

Even if you know very little about the subject, you who are reading this right now probably have a better understanding of bonsai than I did back when I first saw the trees pictured above. I knew nothing. I could see the plants I was being asked to care for looked miserable, but I thought they looked that way because they were bonsai trees. I thought the act of making them into bonsai is what made them miserable! I thought if they were freed from those cramped little pots and allowed to grow without being cut back all the time, they might recover and look good again.

It is worth describing all this for the sake of establishing exactly how humbly bonsai at The North Carolina Arboretum began. Our first trees were notable mostly for their compromised health and poor aesthetic quality. The person who was ultimately tasked with caring for them and developing them into something better knew nothing about them, and did not welcome the prospect of learning. Add to that the fact that Asheville was not even on the bonsai map at the time, meaning there was no good local source for expert guidance, and the resulting picture is not one of particular promise.

But as it turned out, although no one could have predicted it at the time, all the necessary parts were perfectly in place for something extraordinary to happen.

Chinese Banyan (Ficus retusa)

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens)

Black Pine (Pinus thunbergii)

Paper Flower (Bougainvillea glabra)

Boxorange (Severinia buxifolia)

Dwarf Garden Juniper (Juniperus procumbens nana)

Pondcypress (Taxodium ascendens)

Cork-bark Chinese Elm (Ulmus parvifolia ‘Corticosa’)