Pest Management - Part 2

Plants are the ground floor of the food pyramid, and as such have the greatest number of things feeding on them. If a grower eradicates all the harmful bugs on a given crop, be it bonsai or tomatoes or what have you, it's only a matter of time until another population of plant eaters turns up. The grower once again douses the crop with insecticide, the problem temporarily goes away but then returns, and the sequence is repeated however many times over. Aside from the inconvenience and expense of constantly reapplying the pesticide, a person might well decide that this method is an acceptable way to go about the business of producing plants that bear no signs of pest damage. You may not be able to kill them all, but you can kill them again, and again, and again, and again.

The problem here goes back to that whole pesky business of the web of life, and the fact that all living things on the planet are in some way connected. Your intention may be to do away with the aphids (or mealybugs, or spider mites, or whitefly), but in so doing you are also causing a certain amount of collateral damage in the population of other creatures, including those who, unmolested, might help keep the pest numbers at an acceptable level. What constitutes an acceptable level? If your idea is to produce perfection — that is, plants completely free of any cosmetic defects — then your acceptable level of pest presence is going to be impossibly low. The question you might want to ask yourself is, Where did I get the idea that plants are supposed to look perfect? In gardening catalogs and bonsai books the plants may look perfect, but this has much more to do with the arts of photography and photo editing than with the reality of living plants in nature. Look at plants in the fields and forests: Their leaves are often full of holes or covered in fungal spots, ever more so as the growing season progresses. Most of these plants are overall healthy. It is part of their real-life, natural appearance. We may not want our bonsai or garden plants to be completely disfigured, but a few holes or spots can be tolerated for the sake of not poisoning the environment.

Hickory leaves in the forest, summer

Another source of our illusory ideas about perfect plants comes from the people who are ready to sell us the products necessary to achieve these impossible results. Since the end of World War II, when many of the munitions industries converted from the production of weapons to the production of synthetic chemical fertilizers and pesticides, a great revolution has occurred in the production of food. Bypassing the whole argument about whether this is an overall good or bad development, it is safe to say that the changes wrought by this revolution have spilled over into many areas of modern life and particularly those that have to do with growing all kinds of plants, including bonsai. The end result of this can be witnessed in our tendency, when faced with a plant that looks unhealthy, to reflexively think, What can I spray on it?

One of the greatest dangers inherent in the use of chemical pesticides is that they are relatively cheap and easily available to anyone, regardless of the competence, intelligence or sanity of the buyer. These are dangerous and often lethal substances that can be purchased in quantity at the nearest big-box hardware store. The safety of these chemicals depends on the applicator using them the correct way, and especially at the correct rate. Overuse of pesticides is commonplace, and one of the pitfalls of this is that the targeted pests can and do over time build up resistance to the chemicals. Then it takes more and more pesticide to achieve ever-decreasing results. Meanwhile, presence of the chemicals builds in the environment and begins to affect non-target life forms, sometimes including humans.

The subject of petrochemicals used in plant production and their impact on the environment is expansively complex and I am no expert on it. But I am responsible for a valuable collection of ornamental plants displayed in a public garden, and I feel the need to practice some degree of pest management, and to do so responsibly. (As an aside, I rarely ever use pesticides in my home landscape.) Over time I have adopted certain best practices and identified a few behaviors generally to avoid as regards using these powerful chemicals. To conclude, I now share these with you:

Think of the plants you grow as being part of overall nature and not somehow separate from it.

Recognize that the “kill them all” approach to pest management is not sustainable and does not actually work. If it did, plant pests would have disappeared long before now.

Exercise a realistic tolerance level for the presence of pests. It may be necessary to respond when you recognize a real problem, but some small degree of pest presence is not automatically a problem.

Always try to diagnose a plant problem before doing something about it. Knowing exactly what you are dealing with will help you make intelligent choices as to how the problem should be addressed.

For that matter, wait until there is a problem before deploying a solution! The practice of putting out insecticides as a preventative or prophylactic measure sounds plausible, but often the real effect of this practice is to help pests build a tolerance to the chemical being used.

Always use the least toxic effective response possible. Sometimes a strong spray of water from a hose is enough to dislodge damaging pests and wash them away. Horticultural oil and insecticidal soap are effective but relatively benign first options as far as insecticides are concerned, and are less likely to have a lasting effect on the environment.

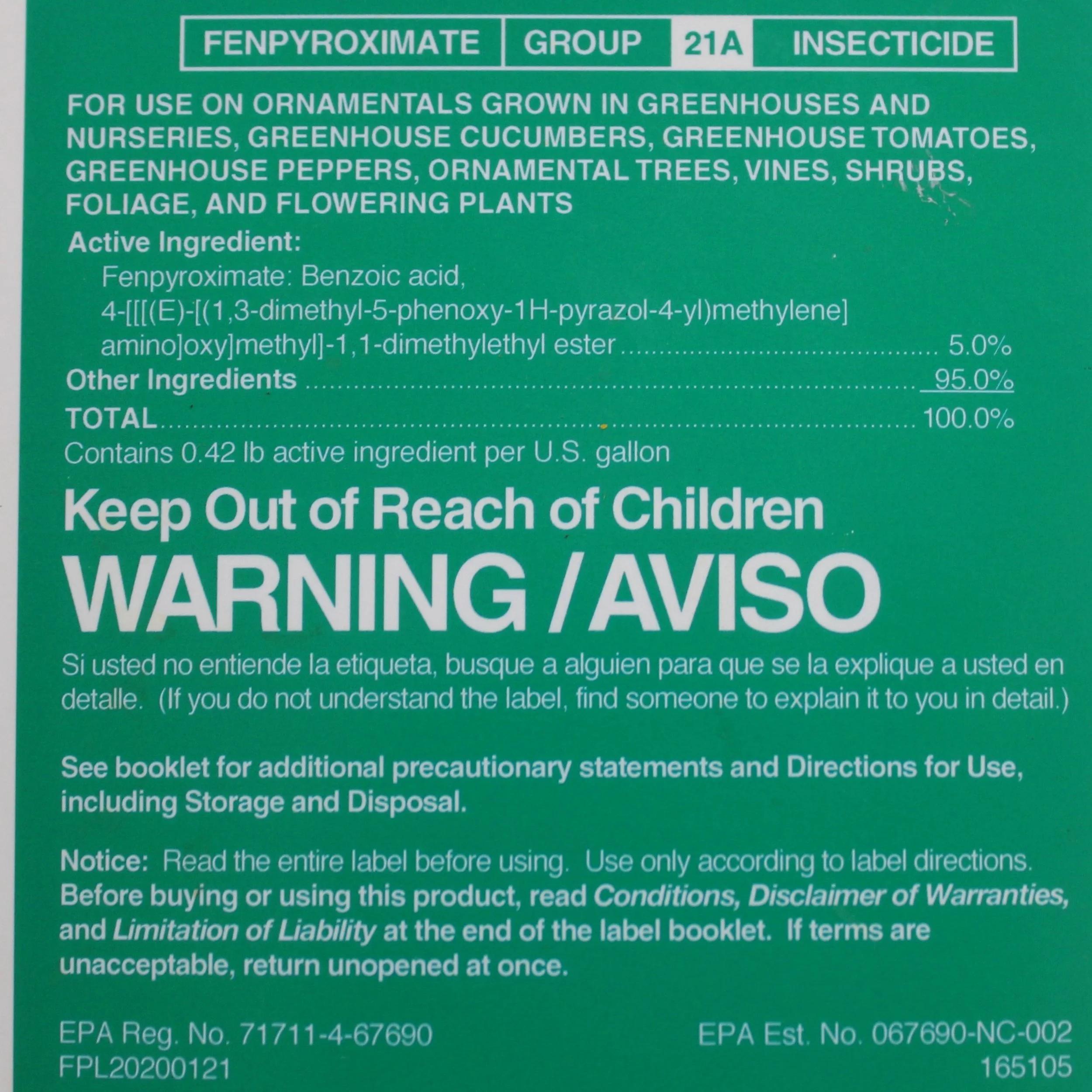

When using any pesticide, read the label beforehand. The label gives information about the proper rate of use for the chemical, how and when to apply it, the pests it is intended to kill, the level of danger it poses to the environment and the user, and the personal protective equipment necessary for applying it safely. The print on the label is usually very small and there is a lot of it. It is not exciting reading, but the labeling contains critically important information.

Avoid using systemic insecticides. These chemicals have become very popular in recent years, and why not? The latest in a long line of miracle solutions, all one need do is apply the chemical once and for a period of time no insect will eat your plant without paying the ultimate price. Of course no pollinators will be able to drink nectar or bring back food for their offspring or the rest of the hive without potentially experiencing the same result. And predators who feed on the bugs that eat your plants may also eventually suffer the consequences as toxins build in their systems.

Be on the lookout for the presence of beneficial creatures, and, if they are there, give them a chance to do what they do. A plant displaying a minor case of aphids, for example, that also has a lady beetle larva or two actively eating the aphids, should not be sprayed.

If you can afford to do it, purchase beneficial insects and release them in your garden or growing area. Sources for these can be found online. Work with nature rather than against it.

Along the same lines, grow your plants in the healthiest manner possible. Healthy plants are more resistant to bug and disease attack. Over-stressed plants are more susceptible to problems, just as over-stressed people are. Consider that the persistent presence of plant pests is often a symptom of a problem and not the problem itself; treating the symptom will provide no lasting relief from what is truly wrong.

Modify your ideas about perfection in nature. Bonsai fall into the category of ornamental plants and as such their looks are paramount, so this is no small matter. Still, there is a price for everything and the price for the illusion of perfection should be considered. Is compromising the integrity of the greater world of nature an acceptable price to pay for having unblemished leaves on your plants? This seems a matter of personal choice, yet the sum of all our personal choices has real effect on the living world around us.