Golden Heart

There are objects that can be seen and touched, existing in their own right with their own identity, purpose and story, that can be appreciated simply for what they are, but at the same time serve silently as a reminder and become a symbol of something much more than what they appear to be on their surface. Such an object may contain the memory of a person who once existed and no longer does, or represent something of value that is itself more than it seems. Such an object may, behind a humble face, be an agent of profound affect.

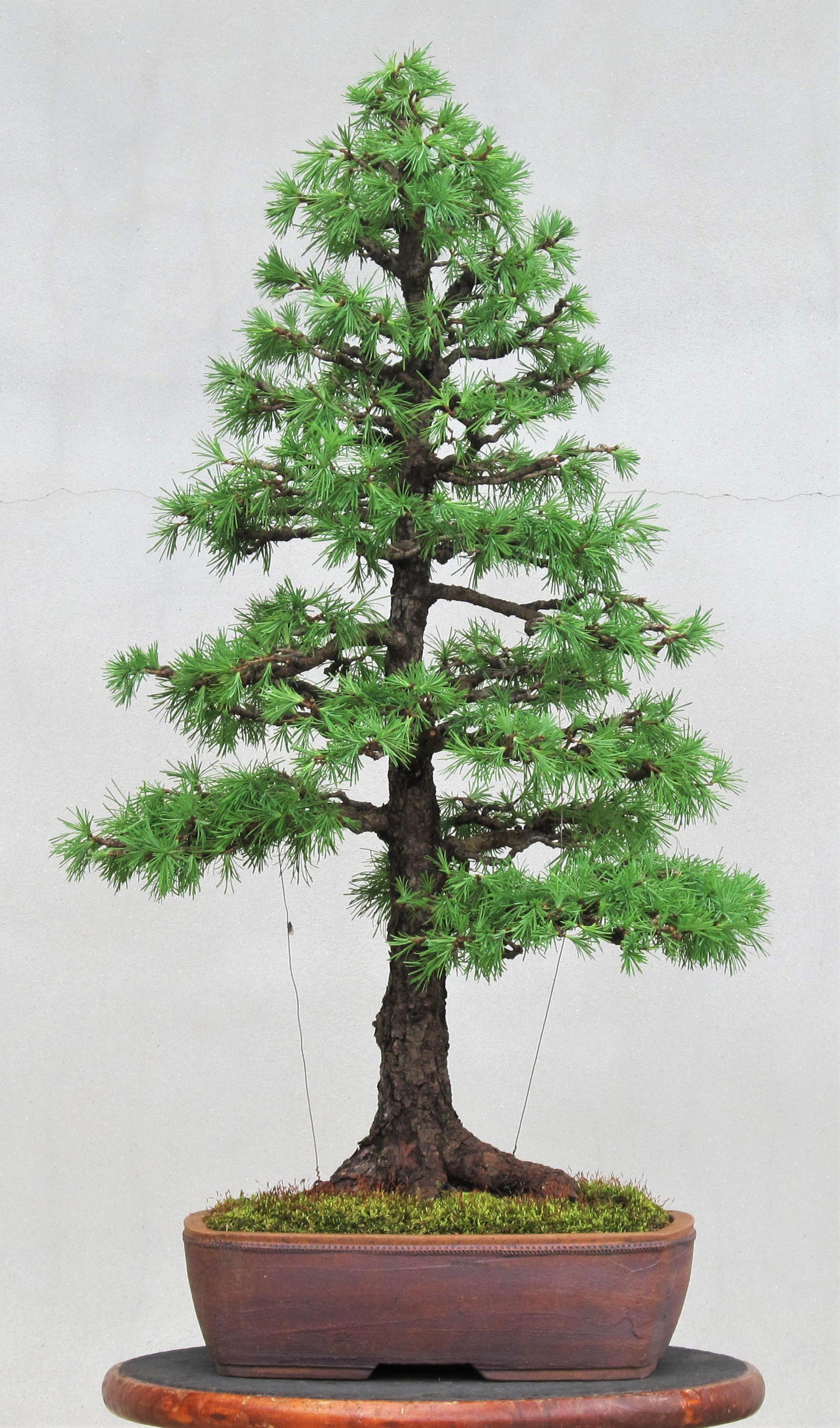

Tamarack is one name for a North American tree species that is botanically known as Larix laricina. Other names include hackmatack, eastern larch, red larch, black larch and American larch. It is one of the most common trees in the northern part of the continent, from New England to Minnesota, across a vast stretch of Canada and on up into Alaska. The species is notable as a deciduous conifer, its needle foliage turning a warm yellow in autumn before dropping off and leaving the tree bare for the winter. Tamarack is frequently used for bonsai in colder regions, often starting out as naturally dwarfed plants collected from the wild. They do not favor warmer climates, however, so they are not to be found in the Southern United States, as bonsai or landscape specimens, except in the higher altitudes of the Southern Appalachians.

The Arboretum's bonsai collection features only one Tamarack, but it has been with us a long time — it was received as a donation in 1995. The little tree paid us a visit, though, before coming here to live. In 1992 the Arboretum hosted a show provided by the Blue Ridge Bonsai Society, which was not only the first bonsai show held here but also the first plant show of any kind we hosted, and the tamarack was part of it. I had never seen a bonsai show before, and when I walked through the tamarack caught my attention. If anyone had been interested in my opinion at the time, I would have given that tree "Best in Show." Nobody asked me because I knew nothing at all about bonsai then, this being before the Arboretum had a bonsai collection and before caring for one became my responsibility. But I was interested enough in the tamarack to take a photograph of it and to inquire of a club member who was standing nearby if the tree belonged to him. He said it did not, that it belonged to a friend of his named Dot Wells.

Ms. Wells’ tamarack at the bonsai show, 1992

Dorothy Wells, known as Dot to her friends, was born and raised in Asheville, and graduated from UNC Chapel Hill. Her career was in nursing and she worked for many years at the Veterans Hospital in East Asheville. She was a great lover of the outdoors, spending most of her free time hiking in the mountains or gardening, and somewhere along the way she picked up the bonsai bug. Ms. Wells was a charter member of the Blue Ridge Bonsai Society, which came together sometime in the 1970s. In 1995, three years after that fateful bonsai show, I received a letter from Ms. Wells. By that time the Arboretum had received the initial donation that started our bonsai collection and I had been put in charge of it, and Ms. Wells had reached an age where it was necessary to divest of most of her bonsai holdings. She contacted me to see if the Arboretum had any interest. I went to her home and looked around, and, sure enough, there was the little tamarack tree. She sent it back with me to the Arboretum.

Bonsai has depth; one can spend an entire life learning about it and never know everything there is to know about it. In 1995 I was at the very beginning of my personal bonsai learning curve, working with the trees in the Arboretum's collection and trying to figure out how to make them better. I didn't know much. The tamarack Ms. Wells had donated was designed in what is called the formal upright form, which is defined by having a trunk that is straight, without curves or bends, and standing perpendicular to the ground. We didn't have any other formal uprights in our collection at that time, so I was keen on making this tamarack, already appealing to me, into the best formal upright bonsai possible. I spent a lot of time studying it and decided that what had been the back side of the tree ought to become the front, and the number one branch — the lowest and largest branch on the tree — needed to be removed. Making decisions like these has become commonplace over the years of my career, but back then it represented a bold and risky proposition. I took a deep breath, made the changes, and when all was done looked at the result and decided it was okay. I hadn't messed up.

Then I thought of Ms. Wells. I hadn't consulted with her about making this big change to her tree, and she lived right in town. It was only a matter of time before she showed up to see how the tamarack was doing. What would she say when she saw what I had done? Suddenly the thought of upsetting her made me anxious.

And sure enough, Ms. Wells dropped by soon after. I greeted her cheerily to cover my nervousness and then we walked together out to the hoop house where the bonsai were kept, and we looked over all the trees and talked about them. When we came to the tamarack she stopped. She looked at it. "You changed the front?" she asked. "Yes," I said. She was silent a moment, then reached out her hand and gently touched the tree. "You cut off the first branch?" she asked. "Yes, Dottie, I did," I said. Again she was silent and I braced myself. She looked at me, her weak old eyes a little teary. "I always thought that should come off," she said, "but I never had the nerve to do it!"

Over the years a great deal of work has been done on this particular bonsai, although the removal of the lowest branch back when we first received it was probably the most dramatic alteration it ever underwent. It has remained a formal upright all the while, filling in considerably over time as any bonsai will do if well tended as it ages, producing more ramified branching. It has been planted in a number of different containers along the way. Here is a gallery of portraits made of this tamarack, going back to its beginning with us in 1995 (click on the first image and then scroll through to watch more than three decades of growth and refinement):

In addition to being the only tamarack, and one of only two formal uprights in our collection, this specimen is one of the very few donated bonsai for which we have precise information regarding its origin. Ms. Wells started the tree from a one-year seedling, which she collected in Leelanau County, Michigan in 1974. She trained it as a bonsai from that point onward, so it has lived virtually its entire life in a container. Ms. Wells collected several other tamarack seedlings from the same place at the same time, and three of these were eventually planted in the landscape of her East Asheville home, where she lived for nearly fifty years. They are still alive, standing about forty feet tall and measuring more than a foot in diameter four feet above the ground. In contrast the tamarack bonsai is currently thirty inches tall and two inches in diameter. I recently took our tamarack bonsai to the former Wells residence to visit with its siblings:

This humble but durable little tree has a poetic name: Golden Heart. It can be said, and not inaccurately, that this poetic name refers to the beautiful golden yellow color the tamarack turns every autumn. A quietly glorious sight to see. Here is a progressive sequence of images made last year when Golden Heart produced a particularly pleasing autumn display (all images made in the month of November):

This bonsai is called Golden Heart for another reason, though, and it is something few people know about. It refers to Ms. Wells, whom I call Ms. Wells in this writing but never called by that name when I knew her. She was always Dottie to me. She and I became friends of a sort, although I never spent a great deal of time with her. She would come by the Arboretum now and again and we would talk a little. Once the Carolina Bonsai Expo began in 1996, she attended every year while she lived. One Christmas eve when my young family and I were heading out of town to visit relatives, we stopped by for a brief visit with Dottie at her house. Because she was quite old and lived by herself, we thought it might bring her some happiness to have a little company, and especially the company of young children, on that particular night. Later when I went to study in Japan for a month, my wife Christine invited Dottie to our little house for supper one evening. I went to Dottie's house on a couple of occasions to do odd jobs around the place that she couldn't do herself, and the last time I did we had a disagreement. She tried to pay me for helping her and I refused to take the money. She later mailed it to me as a check, but I never cashed it. We fell out of contact for a while over that, and next I heard her brother Charlie from up north had moved in with her to help out, because Dottie's health was in decline. She was in her nineties by this time.

One day Charlie called and asked me to come to Dottie's house. She was frail now, in a recliner and covered with a blanket, and she didn't say much. Charlie did the talking. He told me Dottie wanted to give the Arboretum a fairly large financial donation for support of the bonsai program. She didn't want it to be used for anything else and she especially didn't want it used "for someone to take a junket somewhere to have a good time," as no-nonsense Charlie put it. I suggested that Dottie might offer the money to the Arboretum with the stipulation that it be used to establish an endowment for the bonsai program. I didn't really know much about endowments, but I’d heard it was good to have one. Dottie liked the idea and followed up on it. Her very generous gift became the principal of the Arboretum’s bonsai endowment, to which other donations have been added over the years. The Arboretum set up the endowment in a way that the principal is never spent, so Dottie's money is still there, helping to generate interest that goes to support bonsai operations. No one ever used any of it to take a junket.

Not too long after that Dottie went into Hospice care. On one of my last visits with her, Charlie surprised me by asking why I called his sister "Dottie." He said no one else ever called her that; her friends all called her Dot. I was embarrassed because I had no idea why I called her by that name, but I always had and she never corrected me. I apologized. Dottie, who had been lying there with her eyes closed, opened them a little and looked at me. She smiled faintly. "I never minded," she said.

Tableau at the 2001 Carolina Bonsai Expo, honoring Dorothy Wells and announcing the naming of her tamarack.

Golden Heart was the logo tree for the 2001 Expo (image from a T-shirt)