Three Small Packages

Modesty becomes a bonsai.

Big bonsai — the kind that take two people, or four people, to lift and move around — can be impressive just because of their size. The concept of placing emphasis on the very largest examples of something specifically known for being small is confusing, but there is an undeniable cache to big bonsai. The Arboretum's collection has some of these, but we almost have to have them because we have a large display space to fill. Those big specimens don't look so big when you encounter them in our garden! Most people who own bonsai shy away from having super-sized little trees simply for the impracticality of dealing with them.

At the other end of the spectrum there are bonsai so small they fit easily in the palm of a person's hand. It might seem redundant to speak of miniature bonsai, but the phrase delineates those specimens that are the smallest of the small. If you are charmed by a two-foot-tall tree, you will be amazed by one that measures only six inches. The trouble is, keeping a tree so small pushes the limits of its tolerance and makes maintenance much more involved. We don't have any true miniatures in the Arboretum's collection because they are too fragile and demand too much attention. To say it plainly, they are too much work.

Then there are the ancient, naturally dwarfed trees collected from the wild, often featuring incredibly complex amalgamations of sculpted deadwood. These are the very kind of bonsai that win awards at major shows. Quality specimens of this sort are relatively rare and much sought-after, and they sell for unbelievable amounts of money. The very best of them are styled by famous bonsai artists or people who aspire to that status. Most people who own bonsai don't have trees of this description and never will, but exclusivity is a major part of the attraction. The Arboretum's bonsai collection includes just a few older collected specimens of note.

Bonsai that are very big, or very small, or very old tend to be the kind of bonsai that attract the most attention. It is their novelty that makes them so appealing. But the fact is that most bonsai do not fit into any of those three categories, and so it should come as no surprise that most of the bonsai in the Arboretum's collection don't fit into those categories either. The majority of our bonsai are more common. I hesitate to use that word because it might be misconstrued to mean that our little trees are nothing special, that you might find bonsai like ours just anywhere. I don't think that's the case. I think our bonsai stand out for their good health, diversity of species, and the quality and originality of their design. They are common in the sense that they are not sensational; they are not meant to loudly proclaim their own importance. Our bonsai are more quiet. They are modest, and that is not the same as being without merit.

What follows are three accounts of three modest pieces from the Arboretum's bonsai collection. Each of these bonsai is regularly displayed in the garden, and, although I've never heard any of them described as being anyone's "favorite," each of these bonsai is quietly successful. They do not scream for your attention, but they warrant a little piece of it.

'Zuisho' Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Zuisho’)

In 2000 the Arboretum received a bonsai collection in donation after the owner had passed away. It contained a large number of plants, but they were mostly young and not so well developed, so not anything of use for our collection. We decided to auction them at an upcoming Expo in order to raise funds in support of the bonsai program. In a last-minute review, there was one pine that stood out for its small-needled foliage and I impulsively set it aside.

The first available photograph of the little white pine is from early in 2009. In it we see a still very young tree being trained into the shape it would ultimately grow to assume:

2009

The following images show the tree on display in the bonsai garden in 2011 and 2012. At this point the comparative youth of the plant material remains noticeable, but the pine is already projecting a more aged form (click on either image for larger view):

Not only does this specimen have agreeable looking foliage, it is also a surprisingly strong grower. It has filled in well from year to year, as seen in this image from 2019:

2019

Here is how the white pine looks today:

2023

The stylistic layout of this bonsai is Neo-classical, but in recent years it has been grown in a loose, more naturalistic fashion. In the above image, the yellow needles let you know it's autumn.

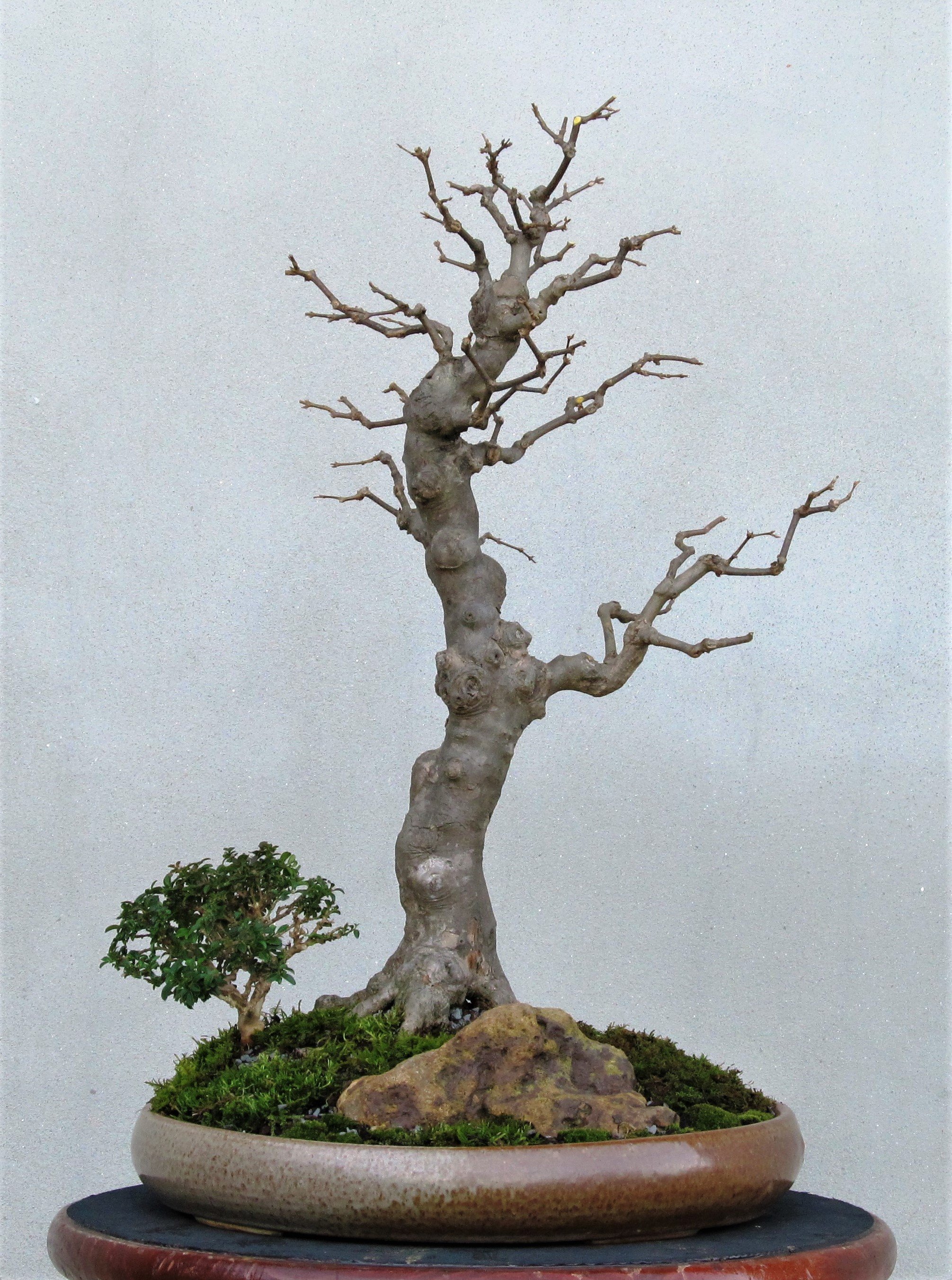

Trident Maple Landscape (Acer buergerianum)

Sometime in the mid-2000s, while on a visit to the Triangle Bonsai Society in Raleigh, North Carolina, a club member offered the donation of a single trident maple. The man who made the offer said the maple was one he had propagated along with numerous others, and he had more than he needed. The tree was little more than a trunk with a few twigs poking out of it, but the price was right so the little maple made the ride back to Asheville with me. This photograph from 2010 was the first made of the tree, showing it still in a plastic training pot:

2010

There wasn’t much to the little maple when we received it and several years of growing at the Arboretum did not yield encouraging results. The trunk was lumpy from many old pruning scars and there was a noticeable deficit of branching on one side.

Three growing seasons later overall branch development had improved a little, but branch distribution was still strongly one-sided:

2012

This specimen might have been a likely candidate for grafting. New branches could have been introduced in places where they were desired, but that approach was never so appealing to me. Instead, I wanted to see what could be made of the tree if its perceived faults were accepted and worked with as a design challenge. Some trees are scraggly and predominantly one sided — that’s their nature. Given the right context, such a tree can be evocative of the struggle to survive.

In January of 2015 I brought this tree with me on a visit to the Greater New Orleans Bonsai Society and used it as the subject of a demonstration. This was the result (click on any image for full view):

The strategy for dealing with the ungainly, imbalanced character of this tree was to build a context for it that introduced mitigating features. The stone and the dwarf azalea (Rhododendron cv.) create visual interest in the lower half of the composition.

Two years later I thought the little landscape was good enough to be on display in the bonsai garden (click on either image for full view):

As seen in the images above and below, this piece was designed to be flexible in its capacity for presentation. Here are pictures of the summer and autumn appearance of the maple landscape in 2020 (click on either image for full view):

This image from earlier this year shows new foliage emerging on the maple, creating a scene reminiscent of springtime in the higher elevations:

2023

Cork-bark Chinese Elm (Ulmus parvifolia ‘Corticosa’)

There are so many reasons to appreciate Chinese elm as bonsai material, and not least among them are the ease with which they can be propagated and the rapid rate at which they can be developed. This specimen was started at the Arboretum as a cutting sometime in the late 1990s. I was growing a number of them and this particular one was slow to take shape. Frustrated by not seeing much promise in the way it was heading, one day I lopped the top off of it. This photograph, the first for this elm, was made a few years later in autumn of 2010:

2010

This approach to styling a bonsai might seem a little drastic, but I was reacting to a phenomenon I had repeatedly come across when observing trees in nature. Some of the most intriguing tree shapes are the result of cataclysmic damage and subsequent recovery. Tops sometimes break out of trees. If the event does not kill it, such a tree will put itself back together and go on living, its physical appearance forever altered. For this particular elm bonsai, that cause-and-effect sequence is both the actual and suggested story of its existence.

Three years of growth subsequent to the damage produced this stage of development (click either image for larger view):

Three more years of development and the form of this tree is beginning to take shape (click either image for larger view):

The following set of four images shows an in-the-round view of the little elm in the spring of 2018. It is particularly satisfying to note that this specimen is designed in such a way that it is not only credible as a depiction of a rugged tree in nature, but virtually any way you look at it the composition is aesthetically presentable (click on any image for larger view):

Here are two seasonal views of the elm on display in the bonsai garden (click on either image for larger view):

The corkbark Chinese elm as it currently looks, a modest little bonsai speaking volumes in a quiet voice:

2023