The Long Game

When I want to write about a bonsai in the Arboretum's collection the first thing I do is head for the digital image archive. There are pictures of little trees in that archive dating back to 1993, the first full year of bonsai at the Arboretum, but the early years are sketchy. In the 90s and early 2000s I would take photographs only now and then when I thought of it. Over the years I came to better appreciate having documentation of how our trees looked earlier in their development, because they change as time goes by. Sometimes you don't even know how much they have changed until you see a photo from years earlier. Now I make a habit of photographing as many of our bonsai as I can, as often as I can, even to the point of excess. I've learned to be a ruthless photo editor just to keep the number of images manageable.

That's why I could not believe it when I went searching for any early images of the Japanese white pine (Pinus parviflora) that is the subject of today's entry and found none predating 2016. The tree came to us in a donation in 1998. I can say this with certainty because I have a copy of the acknowledgement letter sent to the donor, E. Felton Jones. The letter describes the gift this way: One Japanese Five Needle Pine (Pinus parvifolia) bonsai, slanting style, approximately 70 years old, imported from Japan, 17" in height, planted in a round, unglazed Japanese stoneware container. That information still exists because it was written down and saved. It seemed impossible that no picture was made of the tree in the first eighteen years we had it, so I looked some more, this time rummaging through the print image file. There, amongst the trove of old printed photographs, I found one showing the pine I was searching for as it looked when on display at the 2000 Carolina Bonsai Expo:

The picture was made just two years after the pine was received as a donation, so it fairly represents the bonsai more or less as it was when Felton gave it. In 2007 the tree was displayed again at the Expo, this time as part of a memorial tribute to Felton the year of his death. To the best of my recollection this Japanese white pine has never been formally displayed since then. That seems odd. Let's examine the tree while I brush the cobwebs off my memory, and we will see what we find.

Let's begin with what was good, and remains good, about this bonsai:

It has always been a healthy specimen. The health of the plant must be the first concern in bonsai, because without it nothing else matters. The overall health of this pine was good when we received it and has remained so to this day, so poor overall health was never a reason for the tree to be withheld from display.

If Felton's estimate of the pine's age was correct, this tree would have to rank high among our bonsai in terms of age. I have no reason to doubt the number of years Felton ascribed to the tree, but I have no way to verify it, either. The plant appears old, however, by the look of its bark. White pines take a long time to produce mature bark, which is characterized by an accumulation of thin, scaley, exfoliating plates. This tree features mature bark from its base up to its apex. Based on the estimated age at the time of donation, this specimen would now be in excess of ninety years.

This Japanese white pine is growing on its own roots; that is to say, it was not produced by grafting. The overwhelming majority of Japanese white pine bonsai, in this country at least, were started by grafting white pine scionwood onto Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii) root stock. The white pine has smaller, more appealing foliage but the black pine is a more vigorous grower. Grafting helps white pines grow faster. The problem is that frequently the graft union on trees produced this way is unsightly and all too obvious in a bonsai context. It is unusual that this particular white pine was not produced by grafting, and the quality of it as a bonsai is better because there is no aesthetic issue with the tree's base.

With all that going for it, why was this bonsai so seldom displayed? The ultimate purpose of having a tree in our collection is to show it. One factor was a maintenance problem inherent in the shape of the tree as it was styled. The lower trunk of this pine slants strongly and the primary branch projected outward in the same direction as the lean of the tree. As a result, that branch was always trying to make its way while living in the shadow of the upper part of the tree looming directly above it. It is generally true of lower branches on trees that they must reach far out to get sun, but in this case the primary branch had to go even farther because the crown of the tree was stretching in the same direction. A look at the photograph of the pine from 2000 reveals a noticeable degree of weakness in the primary branch:

The weakness of that branch was a chronic concern. The apex of the tree needed to be constantly thinned out to allow more light to penetrate to the foliage below, while the extending low limb could hardly be pruned at all because it needed to keep all the branching it had in order to maintain viability. Such situations develop on full-sized trees in the landscape, too, but nature has an answer: The branch in the inferior position grows weaker and weaker and eventually dies. In maintaining a bonsai this is rarely thought to be an acceptable outcome.

Although the weak branch was worrisome, that reason, by itself, would not have caused this specimen to be relegated to second class status. Something else was keeping the pine from having its fair share of time in the limelight. Speaking plainly, I think the problem was a lack of visual interest.

Bonsai is a visual art; we display bonsai in hopes of stimulating viewer interest. There can be other important reasons for growing a bonsai, such as the psychological benefits derived from nurturing another living being and the meditative state that typically arises from narrowing your focus to the needs of a little tree in a pot. But when it comes to showing a bonsai, the desire is to capture the viewer's attention. A bonsai of modest appearance presented by itself might stand out by virtue of its singularity, but when bonsai are displayed together in a group, they naturally compete for the viewer's attention. Each individual specimen in a display of bonsai needs to have some individual character that compels visual interest.

One responsibility of a bonsai curator is to be sensitive to the need for visual interest in creating a bonsai display. The Japanese white pine that Felton gave us, while notable for the reasons already stated, seldom generated enough response from me to find its way out on display. Revealingly, it was almost never the subject of a photographic portrait for likely the same reason. An unfortunate consequence of this disinterest on my part was that the tree was neglected in its stylistic upkeep. I recognized the potential value of the pine as an old specimen, however, so the tree was kept and its health maintained. Eventually it was transplanted to a larger container and allowed to grow with little restraint and no attempt at styling.

Those were the circumstances that led to this pine being offered as demonstration material to 2016 Carolina Bonsai Expo guest artist Dan Robinson. In bonsai circles Dan needs no introduction because he's had a long and colorful career as a maverick bonsai artist. Based in Bremerton, Washington, Dan is a "tree guy" through and through, and he likes his trees old and gnarly. He studies those trees in nature and then creates bonsai that capture that wild look. I think of him as the founder of bonsai naturalism in the United States and I have personally learned a lot from his example. I knew if Dan Robinson restyled the old white pine its days of lacking visual interest would be over.

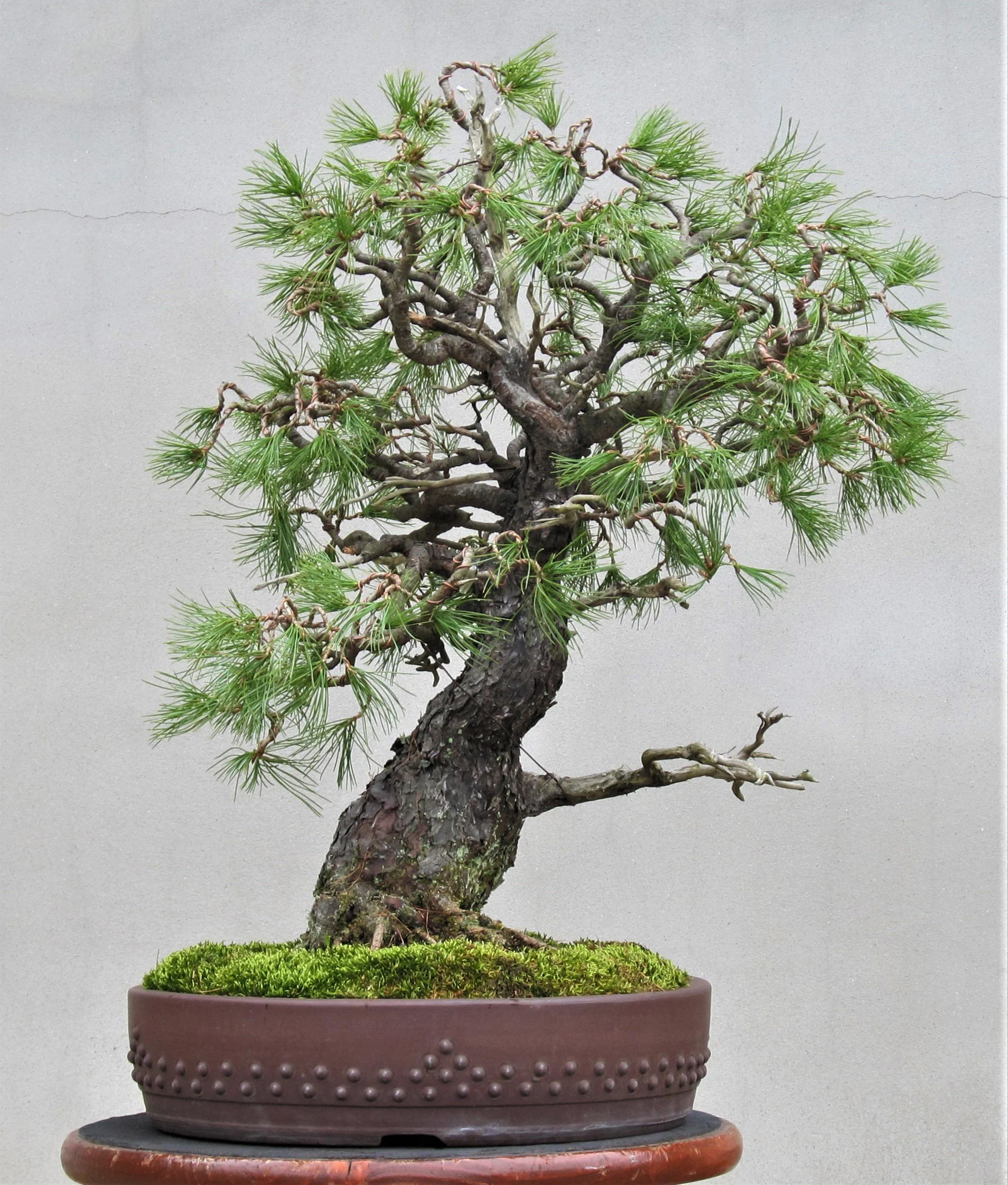

Here is a 360-degree view of the Japanese white pine as it was before the Expo demonstration (click on any image for a larger view):

After a three-hour work session the tree looked like this:

The challenge with this pine was not only to give it a new, more dynamic design, but to deal with an excess of long, leggy branches. A good many branches were removed in the demonstration, and others were intentionally killed but left in place on the tree as deadwood. This was the fate of that problematic lowest branch, which had been chronically weak from being located in a disadvantaged position. Lack of light will no longer be an issue for that branch! All the remaining branches were wrapped in copper wire and then corkscrewed into dramatic contortions. This technique allows for condensing the legginess of the branches while simultaneously giving the bonsai a more ancient appearance.

In order to soften the impact of so much removal, Dan intentionally left a couple of fully formed branches in place that would be removed later, after the tree had regained strength.

I was very pleased with Dan's work. He had transformed the tree and set it on a new path of development, but there was a long way to go before the new design would be fully realized. When a miniature tree is worked over in a demonstration, that event represents just a brief passage in the tree's bonsai career. A great stride forward might be made, as it was in this case, but there is no shortcut to producing a quality specimen. It takes time. It has been six years since our Japanese white pine received its Dan Robinson makeover, and it still has not reached a point where I would feel comfortable putting it out on display. But it's getting close.

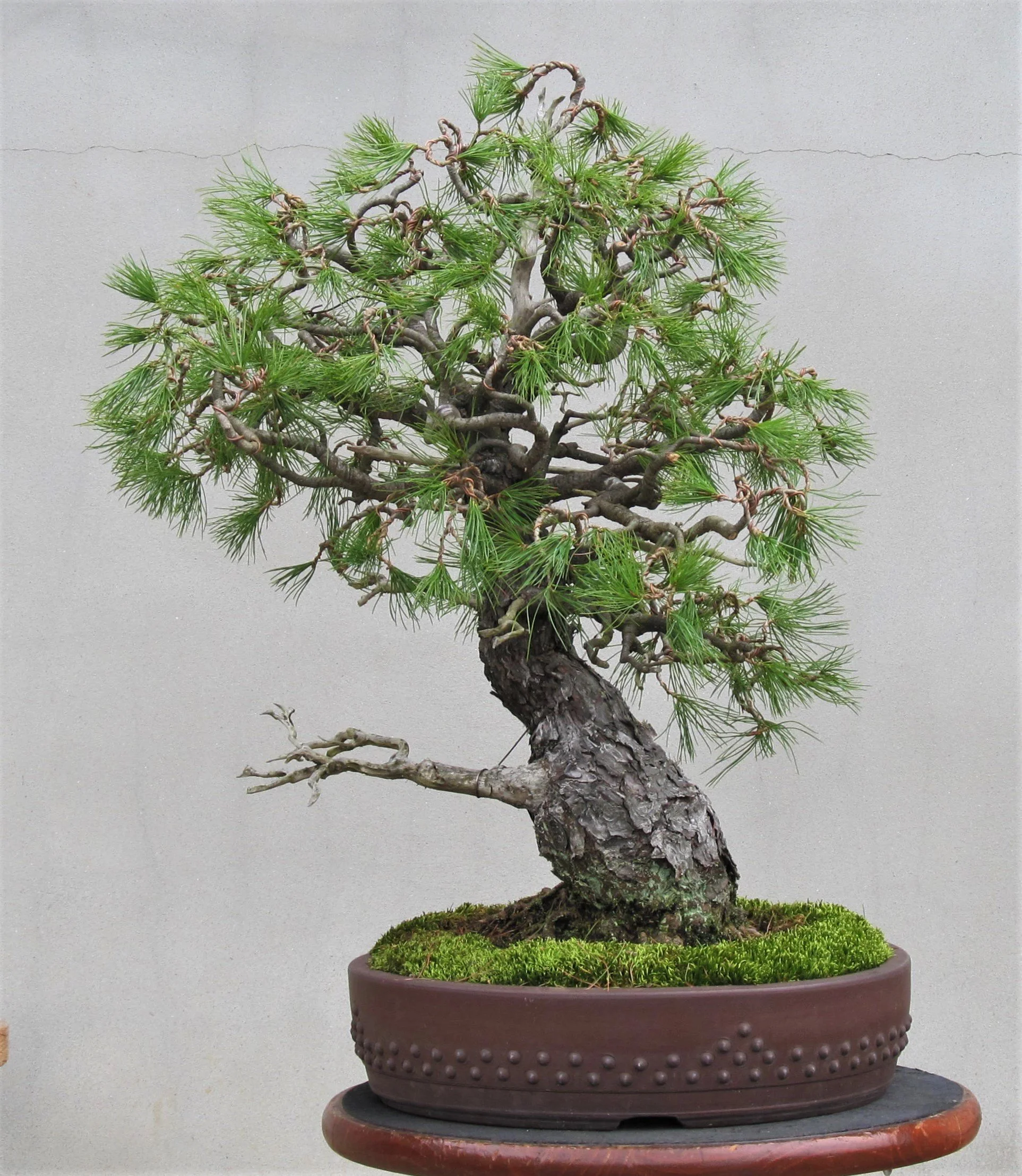

The following set of images presents a 360-degree view from April, 2020 (click on image for larger view):

Three and a half years had passed since the demonstration and the pine was coming along well. It was repotted into a smaller round container in 2019. The wire Dan put on was allowed to remain in place for nearly two years to make certain all the convolutions introduced to the branching would have the best chance of taking hold. The wire bit into the bark here and there but the branches stayed more or less as shaped. At this time the two "sacrificial" branches that had been left on the tree were removed, as they were no longer needed to ensure a healthy recovery. The tree then had a year of growing without any work being done, not because work couldn't have been done but because we have plenty of other trees. We are not being pushed by a deadline in developing our bonsai specimens so it makes sense to work on other trees while giving a heavily-worked tree ample time to get back to full strength. In spring of 2020 I went through the canopy and chased back branches wherever possible to further reduce their sprawl, then completely re-wired the entire tree.

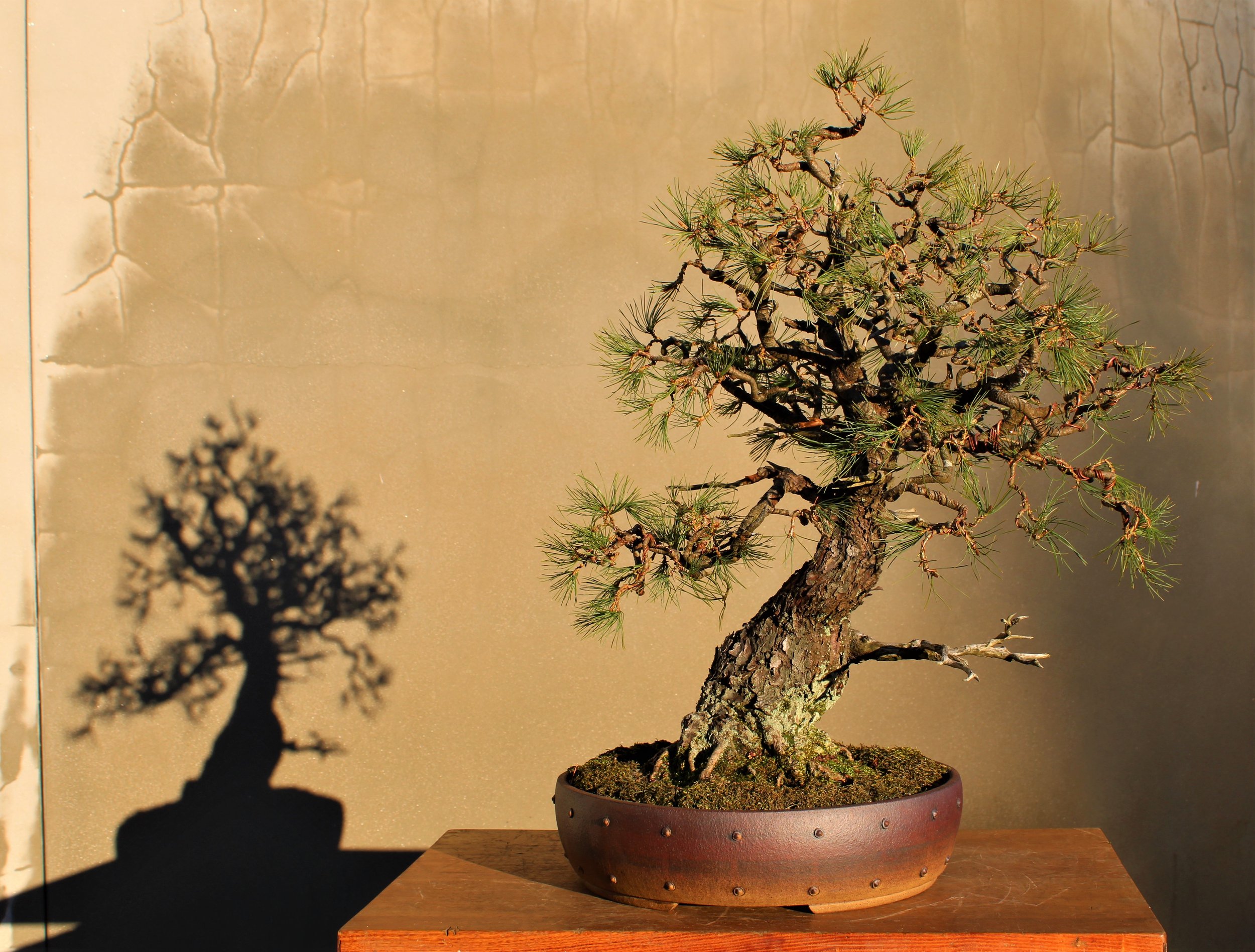

The wire applied in 2020 was removed in early 2022. We also repotted the pine into a custom-made container by local bonsai potter Robert Wallace. By the end of that year the bonsai looked like this (click on image for full view):

Once again, the tree was given a thorough pruning and every opportunity was taken to create openness while condensing the spread of the canopy as much as possible. Then the tree was wired again and all the new growth that had occured since the last wiring session was given the same convoluted shape as the rest of the branching. The following set of images presenting a 360-degree view was made in December of 2022 (click on any image for larger view):

Maybe, if all goes well, this old Japanese white pine will finally make its bonsai garden debut sometime in 2023!

![[Untitled]-.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60f1b6e04b8603014f4926fd/1671147569087-ORJSNY83WPBVOHSMRUXN/%5BUntitled%5D-.jpg)

![[Untitled]-circled.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60f1b6e04b8603014f4926fd/1671147579919-ZQF0J8AJI2BU1TSC98NY/%5BUntitled%5D-circled.jpg)