Japan - Part 3

Going to Japan was never my idea. It was something I heard about right from the beginning, though, from all the bonsai people who took an interest in my work at the Arboretum. These people would ask if I had ever been to Japan and upon hearing that I hadn't they would proclaim that it was necessary for me to go there, that I would never really understand bonsai until I did. No one was more insistent in this regard than my primary mentor, Dr. John Creech. Early on Dr. Creech told me I would someday go to Japan to study, that he would get me there, but not until I had some time to get myself ready so I could make the most of the experience. He knew I was only starting out in bonsai and still had to learn the basics. If I went to Japan prematurely it could overwhelm me, or at the very least I might not know enough yet to ask the right questions.

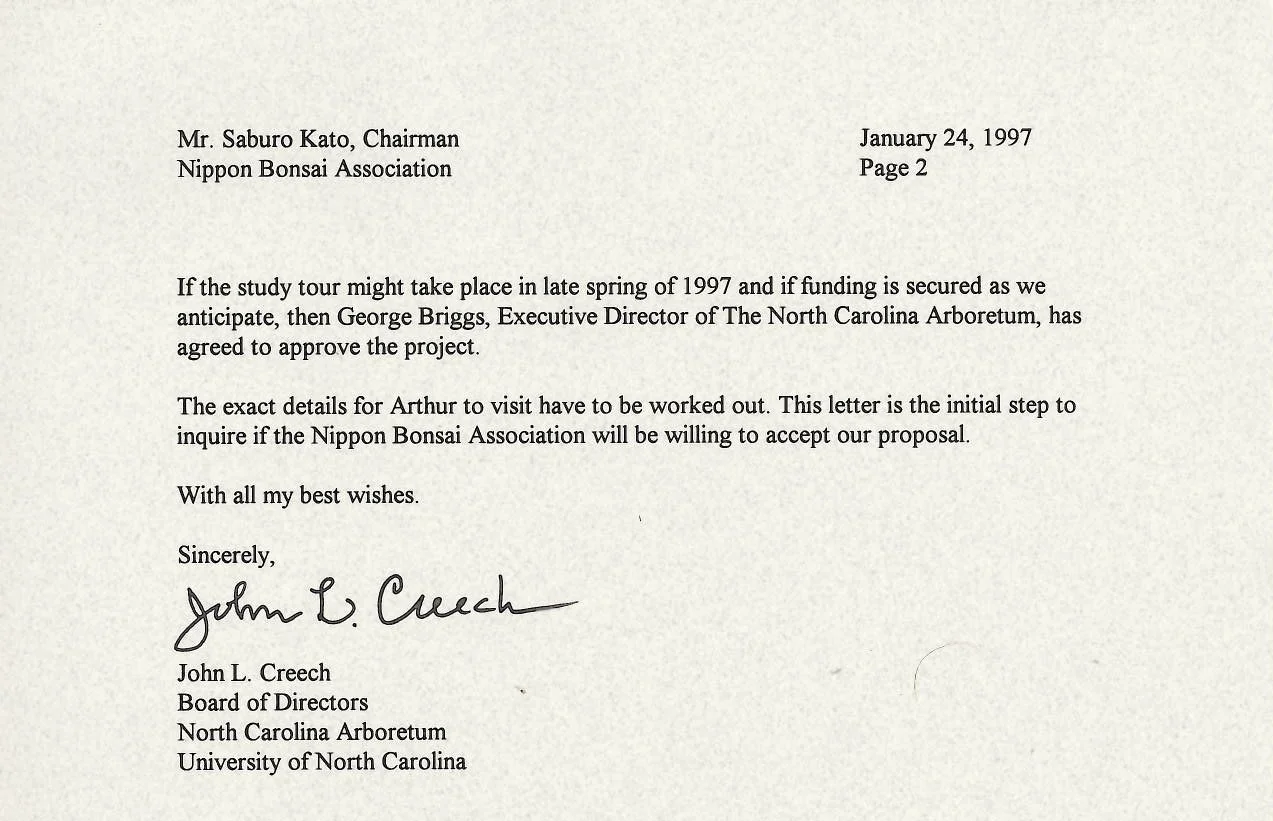

At the start of 1997 Dr. Creech decided the time had come. He wrote the following letter, which was sent to Mr. Suburo Kato, Chairman of the Nippon Bonsai Association:

Dr. Creech's letter was accompanied by one from Arboretum Executive Director George Briggs, and another from me, as well as letters of recommendation from Bob Drechsler and Dan Chiplis (Curator and Assistant Curator of the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum,) Skip March (Chief Horticulturist, U.S. National Arboretum,) Ben Oki and Chase Rosade (noteworthy U.S. bonsai professionals who had been to the North Carolina Arboretum). For half a year there was no reply. Possibly Mr. Kato had put the request aside in hopes it would be forgotten, because it was a big ask. Dr. Creech was patiently persistent, however, and sent a second letter to renew the entreaty. Mr. Kato finally responded, gave his consent and turned over the Japanese end of the negotiations to Mr. Susumu Nakamura, a Nippon Bonsai Association director who was to be my host and teacher.

A letter from Mr. Nakamura, sent after meeting with him in Chicago while he was teaching there.

At this point a fundraising effort was initiated. The trip was to be entirely financed by donations from the small community of supporters that had begun to gather around the Arboretum's nascent bonsai program. Dr. Creech once more stepped to the fore, lending his name to the effort and writing a personal appeal to prospective donors. Checks began to arrive. Some people gave $25 or $50, and some gave much more. Bonsai clubs in Raleigh, Charlotte, Columbia and Atlanta sent generous donations, as did the Blue Ridge Bonsai Society in Asheville. Harold and Tina Johnson, enthusiastic bonsai supporters from the Triangle Bonsai Society in Raleigh, donated a round-trip airline ticket to Tokyo. In the end, enough money was raised for me to travel comfortably and stay in Japan for a month.

These were the extraordinary circumstances that led to my bonsai trip to Japan: Dr. Creech extended himself personally to secure me an exceedingly rare educational opportunity on the other side of the world, and scores of other people voluntarily contributed the necessary resources to make it happen. The Nippon Bonsai Association and Mr. Nakamura sought no compensation for their time and efforts on my behalf. They did what they did only because of their tremendous respect for Dr. Creech. When I went to Japan I was fully conscious of the honor of it. I knew the importance of the opportunity for my career development and future work at the Arboretum, and was aware that others had given generously to enable me to have a once in a lifetime experience I could not have had otherwise. I keenly felt the responsibility of it.

With Mr. Kato at his nursery, next to one of his large Ezo spruce plantings. I saw Mr. Kato on several occasions in Japan and in the United States. This occasion was the only time I saw him when he wasn’t dressed in a three-piece suit.

I have previously shared with you the account of my trip that I wrote soon after returning to the United States, which was published later that year in an American bonsai magazine. That article was written with a bonsai audience in mind, so while it was accurate it was also a tailored rendition, and certain experiences and the thoughts they engendered were kept to myself. I have also shared with you some of the notes I made in the daily journal I kept during the month of my stay in Japan. Those writings captured my real-time thoughts and emotions as the adventure was unfolding, but they were composed in a journalistic way, almost as a form of reportage. Now, twenty-five years later and with the advantage of hindsight, there are certain elements of my Japan experience that I recognize as having had more importance than previously acknowledged. It is time to shine some light on these matters.

To begin, I was not an experienced traveler. Aside from a couple of forays over the border into Canada in my youth, I had never journeyed to another country before. The new luggage I used on the trip was donated by a supporter because I had no luggage of my own. There was an unfortunate amount of time and energy spent, especially at first, dealing with circumstances arising from the nature of long distance international travel that a more experienced traveler would have circumvented. In preparation for the trip I spent time learning about the history and customs of Japan, and this was helpful, but I had started this self-education from scratch and I did not have much time to pursue it. I was obliged to learn as I went and mostly by making mistakes. The fact that I did not know the Japanese language was unfortunate, although my hosts were bi-lingual and many Japanese people know at least some English.

Prior to the month in Japan I had never been away from home for more than a few days at a time, and never since then have I again been gone so long. I like traveling well enough, but I hate being away from home. In 1998 my two children were eight and five years old, and being apart from them and my wife made me feel at times absolutely miserable. My homesickness grew exponentially as the month progressed. Apart from the familial aspect, the home I missed was my own country and culture. I have over the years met many people who are totally enraptured by the mystique of Japanese culture, to the point that they surround themselves with reminders of it and sometimes to the point that they denigrate American culture in comparison . I have never felt that way. You can keep all the sushi and give me some smoky Southern barbecue. You can have Matsuo Basho and I'll stick with Walt Whitman. Japanese culture is fascinating and I respect it, like I respect all world cultures, but I'm an American through and through.

When I went to Japan I expected to see bonsai everywhere, assuming it was a very popular part of everyday life there. I saw many bonsai, sure enough, but only because I was associating with bonsai professionals and traveling in bonsai circles. Otherwise, when moving about in ordinary Japanese society, I saw hardly any. I found out that bonsai in Japan is a niche interest, a specialty market, despite its long history there. Among young people bonsai is considered a relic of traditional culture, like kimonos are. It's something your grandfather might be interested in, and not nearly so appealing to modern Japanese sensibilities as golf is. While among the bonsai professionals (all older men), I heard grumblings of uncertainty about the future of bonsai in Japan and mixed feelings expressed about the growing influx of Westerners seeking apprenticeships.

This leads directly to an aspect of my bonsai study in Japan about which I have rarely ever spoken. Although the bonsai I saw at Kokufu and elsewhere were overwhelmingly impressive, there was something about them that left me cold. I wrote about it in my Japan journal, after taking a trip to the Takagi Museum: Though it was well done, something about the idea of viewing bonsai in a museum setting doesn't sit well with me. The trees end up being like dusty old relics instead of living, growing pieces of nature. This is something that I've been feeling as I see the great ancient bonsai of Japan - that they are almost too precious, that they are too far removed from the reality of the average person, that they are almost perfect to the point of sterility.

No wonder I kept such observations to myself! What would all the good people who made it possible for me to go to Japan so I could experience Japanese bonsai have thought if I had come back saying that? Perhaps they would have thought their generous efforts were wasted on someone who lacked enough sense to appreciate something so obviously good and special. Perhaps they would have felt regretful about having helped me to go there. I could never have done that to any of those people, but I especially could never have done that to Dr. Creech.

Now the time has come to talk straight about it.

My time in Japan was wonderful, challenging, difficult, exhausting, educational, mind-expanding, lonely, isolating, exhilarating, important and memorable. In reviewing the journal I kept while there and reliving the experience in memory, my strongest feeling is one of gratitude — to Dr. Creech and Mr. Kato and all the others who made it possible, but most of all to the Nakamuras. The Nakamuras took me, a foreign stranger, into their home and shared their lives with me for a month. I did not sleep at their house, but I spent a great deal of time there and ate most of my evening meals with them. Mrs. Nakamura was a wonderful cook and fed me and fussed over me and even scolded me sometimes as if I were her own son. Makoto, who was somewhere right around my age, started out as my guide and interpreter on numerous cultural outings, and ended up becoming my friend. He made it possible for me to have an inside glimpse of Japanese life, including its history, mythology, philosophy, food and entertainment. He was a thoughtful, intelligent, humorous and kind travel companion, who helped me navigate and feel comfortable in a society known for its impenetrable tendencies.

Makoto with Mrs. and Mr. Nakamura

My relationship with Mr. Nakamura was sometimes strained, especially in the latter half of my time in Japan when I was studying with him one-on-one. He was a worldly gentleman, knowledgeable and respected in his profession. Mr. Nakamura won the dubious honor of hosting me because he was good at speaking English and was familiar with Americans due to his long history of traveling and teaching in our country. I think he was used to being treated a certain way by his Western students, and I did not have that kind of relationship with him. I hasten to say that I treated him with the greatest respect. I knew of him beforehand by his excellent reputation as a high-level Japanese bonsai professional, and I was fully aware of the honor afforded to me in studying with him, and the extent to which he was inconveniencing himself, without compensation, to take me on as a visiting student. I comported myself with proper deference to Mr. Nakamura's authority and reputation, but I did not come to him as a blank slate.

Dr. Creech had wanted me to wait before going to Japan so that I might be better prepared for the experience, but during that time, while I was accumulating basic bonsai skills, I was also formulating a different idea about bonsai itself. It was a love of nature and particularly trees that brought me to the North Carolina Arboretum in the first place. It was that same affinity that gradually opened me up to the possibility of doing bonsai as my career, once that possibility was proposed to me. Right from the beginning my concept of bonsai had to do with trees and nature, and all the cultural associations between bonsai and Japan were of secondary importance, at best. I warmed up to bonsai as the perfect marriage of art and horticulture, but all the bonsai people I met seemed to think of it as a three-way relationship. Bonsai for them was about art, horticulture and all things Japanese. It was the Japanese Art of Bonsai.

Attribution: Rijksmuseum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At first I was able to shrug this off and focus on learning how bonsai works while developing the skills needed to do it. But over time people’s insistence on tying the cultivation of miniaturized plants to the appreciation of a foreign culture started to become an annoyance. As those people saw it, not only was it undesirable to contemplate doing bonsai without reference to Japanese aesthetics, doing it that way was not actually possible. The product of such an approach could not rightly be called bonsai. I suspected otherwise, but I learned early on that it wasn't a good idea to speak openly about this. I pursued my studies and kept my subversive thoughts mostly to myself, and then one day Dr. Creech announced it was time for me to go to Japan. Then I was in Japan and studying with a world famous Japanese bonsai artist, but my feeling inside was not one bit different. I never in any serious way challenged Mr. Nakamura about anything he taught me. I did ask questions, however, and I did speculate on other possibilities regarding bonsai. I was not nearly as pliable as I might have been had I come there as a true acolyte. Mr. Nakamura was perceptive. I think he had a sense of me being unfortunately corrupted in my bonsai thinking. Still, he never treated me with anything less than dignity and professional courtesy, as well as with the most gracious personal hospitality. I remember him affectionately.

A drawing from my Japan journal. I painted a better version of this image and gave it as a gift to Mr. and Mrs. Nakamura when I was leaving Japan.

Going to Japan was never my idea. Yet the opportunity came to me and I went. I was told I would never really understand bonsai until I went to Japan, and this turned out to be true in an upside down sort of way. I had an idea about bonsai, but until I went to the place everyone associates with bonsai I couldn't know if my idea had merit. Although I kept my innermost feelings secret when I wrote the article for the bonsai magazine, I did put this part in at the very end:

Does a person have to be Japanese, or at least attempt to think like a Japanese, in order to get to the core essence of bonsai? Or is there enough substance to bonsai as an art form, with real connections to the human psyche that it can stand independent of cultural identification and become truly universal? Can we who are outside of Japan ever hope to produce work that is as artful and accomplished without being imitative? Can we find our own voice in this?

It was deceptive of me to pose these questions as some sort of afterthought, when finding answers to those very questions was paramount in my mind during my trip to Japan. I found what I was looking for (Answers: no, yes, yes, and yes.) Although I enjoyed an experience of real personal growth that I will always cherish, the professional outcome of the trip was of equal or greater value. I came back knowing for certain that bonsai can never be in the United States what it is in Japan. Furthermore, I came back convinced there is no good purpose in even trying to make it be that way.

That's why bonsai isn't that way at the North Carolina Arboretum, and twenty-five years along we seem to be doing alright with it.