A Snapshot of Now

In this part of the world, the growing season usually begins in very late February or early March, when the first little leaves pop out on the very earliest deciduous species to initiate new growth. More and more species join in as the weeks progress through March and into April. By the end of April, any woody plant that is still in the game has typically made its opening move, unfurling new banners of green, photo-sensitive tissue under the ascending sun.

In the Arboretum’s bonsai operation, a great deal of repotting is happening in February, March and April. It is desirable with most deciduous species that root pruning, if it is to be done, should happen just on the cusp of the new growing season, as leaf buds swell but just prior to their opening. As April moves into May and then June, the main emphasis in our bonsai maintenance is managing the newly emerging growth. Pruning of new growth varies with each individual specimen depending on what species it is, what stage of development it’s in, and what degree of health and vigor is exhibited. New shoots emerging on established, well-developed, healthy deciduous bonsai will usually be trimmed back to either one new leaf or one pair of new leaves, if the species is oppositely arranged and grows its leaves in sets of two. This is done as soon as practicable in order to slow down the surge of energy being experienced by the tree and to keep the specimen in presentable appearance. The tree gets to grow, as it must in order to maintain health, but the growth is kept minimal.

Trees that are still in some earlier stage of development and not yet presentable as bonsai usually don’t get a lot of attention until around the end of June or beginning of July. The new shoot growth on these subjects is allowed to extend and harden-off before being pruned back to whatever length is deemed appropriate. This practice, while mostly a product of a lack of time, also promotes vigor in the developing little tree, facilitating increased vitality. Vigorous growth also results in faster increase in the girth of branches and trunks. Sooner or later, however, vigorous growth must be brought back under control if the plant is to continue in its proper development as a bonsai. When handled this way, a deciduous species being trained for bonsai use might optimally be expected to still experience two or three growth events in a single growing season.

That which is thought to be optimal is often enough at odds with reality. We might have a plan that anticipates a certain course of events, but that can never be anything more than a starting point, after which things go the way they go due to circumstance. Mitigating factors in the world of bonsai growth and development include, but are not limited to: Weather conditions, incidence of disease and pest damage, accidents, mistakes, poor timing and availability of labor. The point is, the rate at which work on the little trees can be accomplished is variable, dictated by circumstance and bounded by reality. Every growing season is different and the path followed by every specimen is different.

The 2025 growing season has overall been good so far. We’ve had adequate rainfall, and temperatures, while generally hot, have not yet been excessive in this region. Keeping up with all the good growth on the many trees in the Arboretum bonsai collection has been a pitched battle, as it always is, but we have a capable and experienced crew working at it and we remain more or less on top of the situation.

What follows is a quick check-in with two maple trees currently in development.

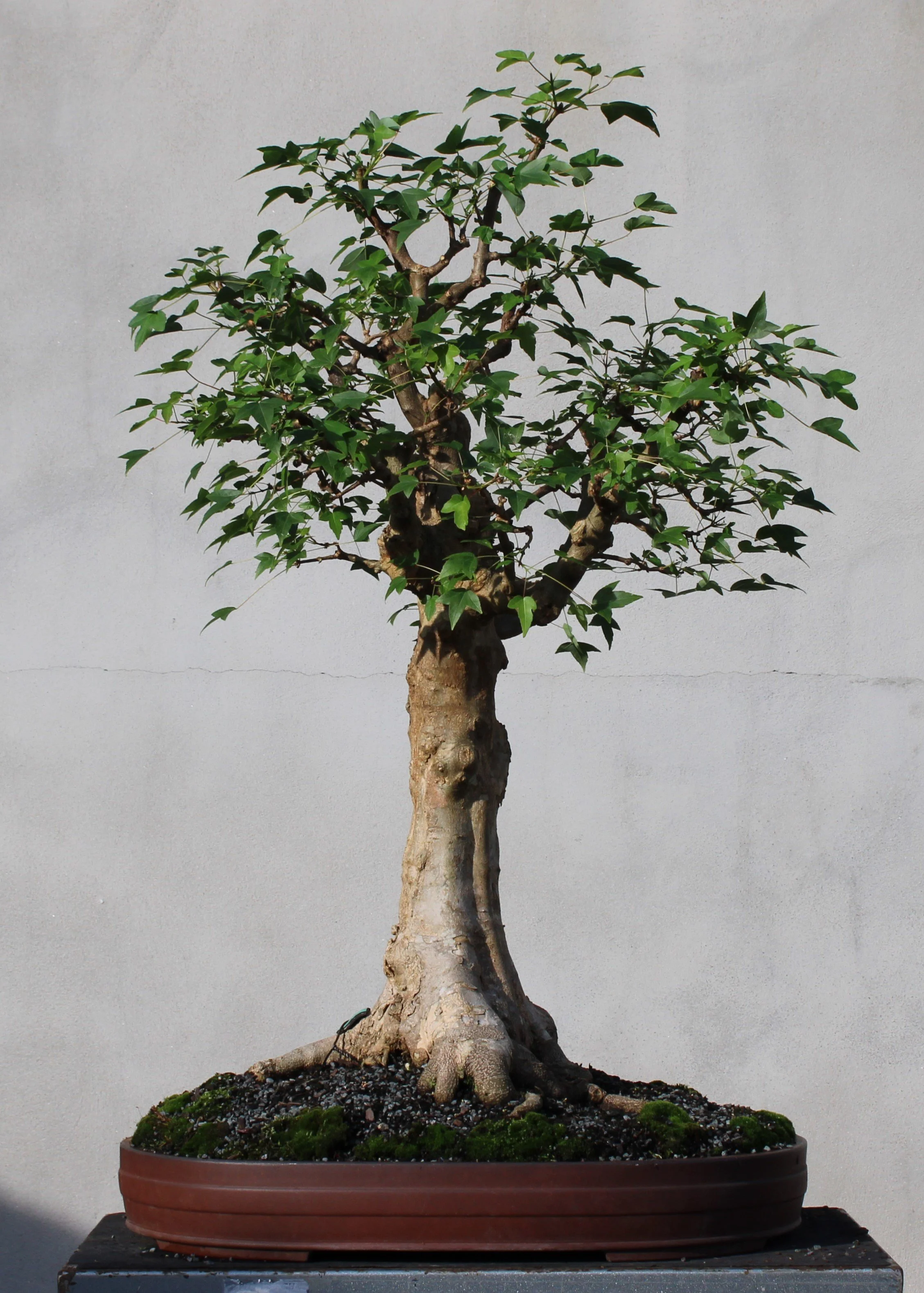

This trident maple (Acer buergerianum) has been featured repeatedly in the Journal, most recently just six weeks ago. In the last work session, the tree received its first pruning since initiating growth in early spring, which was later than the first pruning might optimally have occurred. The trident responded well and looked like this after one month of regrowth:

The season’s second pruning (third overall for the year because the first took place before the tree broke dormancy) consisted of chasing back the latest round of growth to one pair of new leaves. No new styling decisions were made, the crown of the tree was simply pushed back all over:

As can be seen in the above image, the new shoots were about six to eight inches in length, carrying seven or more pairs of new leaves and still extending. Each individual shoot was cut back to leave a single pair of leaves.

After the most recent pruning was complete, the tree looked like this:

The timing of the pruning, although perhaps a little late, was nonetheless very good. The proof of this is that the tree is already pushing out new growth all over, as seen in this picture made just yesterday, out in the hoop house:

Each pruning cut resulted in two new points of growth coming out of the axils of the pair of leaves that were left after the cut was made. This is the anticipated response, although there are no guarantees, and the turn-around time for the new growth can vary considerably. Getting new growth in less than two weeks time is fairly optimal. The newly emerging leaves on this specimen are initially an attractive red color:

The next specimen offered for your consideration is one of our many red maples (Acer rubrum) currently under development. This tree was one of those that came to us as a first year seedling sometime around the year 2000, spending fifteen years or so growing in a pot before being planted in the ground to accelerate trunk growth. Here is the appearance of this maple at the start of 2021, its first year back in a container after being collected from the grow bed:

February 2021

February 2021

No pruning was done on this specimen during the 2021 growing season. At the end of the year it looked like this:

December 2021, before

December 2021, before

With the Arboretum bonsai collection, most of the serious styling work on deciduous trees takes place during the dormant season, from late autumn until very early spring. It is then we have the time to do the work, but the absence of foliage also makes it easier to see what’s going on structurally. This initial styling, depicted in the two following images, set up the tree for development of its eventual form:

December 2021, after

December 2021, after

If someone had asked me at the time what style I was aiming at in giving the maple this initial shape, I would have said that I was intending a naturalistic representation of the broom form. That is, this bonsai would be shaped as if it were a specimen growing out in the open, where the tree had the space to spread out and potentially grow wider than it managed to become tall. This, however, would have been an after-the-fact rationalization. I wasn’t consciously thinking at the time about how the tree would eventually look. Instead, I was thinking about the mechanics of tree biology, how a tree goes about the business of shaping itself in response to its environment. I followed the logic of tree growth, sending limbs in different directions where they could find the space and light exposure necessary to fully express themselves. But I am not a tree, so although I might seek to mimic tree behavior I do so through the filter of a human mind, concerning myself with aesthetic matters such as composition, eye movement, asymmetry and balance. Tree growth in nature is mechanical and random, while tree growth in bonsai is mechanical and directed by human sensibilities. Human sensibilities are all over the place, which makes explaining the creative process a real challenge.

This red maple is a back-burner project. It’s not high on the priority list so it gets attention only sporadically, and its progress is accordingly slow. I like this tree, though, and think it will one day amount to something. The maple received its first pruning of the current growing season just this past week, and to note the occasion I got out my camera and made a new set of documentary images. Here is how the specimen appeared prior to the recent work:

July 2025, before

July 2025, before

And here is how the maple shaped up after a thorough pruning:

July 2025, after, side A

July 2025, after, side B

July 2025, after, side C

July 2025, after, side D

Do not be distracted by the four images above being labeled “A-B-C-D” because there is no qualitative designation intended. This tree has no front. It might be, given how the development is going, that the view labeled “A” is indeed the preferred way to eventually present the tree. The view labeled “C”, in this case the complimentary opposite of view “A”, might work just as well. The view labeled “B” is an interesting alternative, and even “D” might present acceptably when the tree is in leaf. Then again, over time the currently unidentified views E, F or G might emerge as agreeable options. That is to be decided somewhere down the road, when the tree is all put together and deemed to be showable.

In the meantime, other issues are more important. The telltale wound from the trunk-chop made at the time of the tree’s collection is one such concern that was addressed in this most recent work session. Here are two views of how the wound looked initially:

Trunk-chop wound, before

Trunk-chop wound, before

Trunk-chopping is an activity fraught with potential trouble. It is a traumatic experience for the tree and the response is unpredictable, usually resulting in some degree of die-back. The die-back was minimal in this instance, and at this stage of remove from when the chopping was done, the tree has stabilized the damage zone. It can be observed in the above images that the tree has begun to produce the callous tissue to cover the wound site, although the callous is not present around the entirety of the damage’s perimeter. There are also a couple places where the dead wood stands out higher than the living tissue around it, presenting an obstacle for the callous to overcome in its effort to cover the wound. In response, I used a rotary carving tool to reduce the area of dead wood, causing it to be recessed. I also redefined the periphery of the wound, removing tissue until I reached living material all the way around the site. This action will re-initiate the production of callous, hopefully causing it to roll in anew from all sides. The newly exposed dead wood was charred with a miniature blow torch to make it more resistant to insect and disease activity, and the shape of the wound was slightly altered to promote good drainage during rain events. In a best case scenario, the callous will eventually cover over the entire damaged area. Short of that, the exposed dead wood area will be more stable and resistant to decay, and the resulting wound will look more “natural”:

Trunk-chop wound, after

Trunk-chop wound, after

The base of the maple also features some substantial wounds where secondary trunks were removed at the time of collection. These are mostly covering well, although the process is slow:

Basal wounds, before

One of the basal wounds was having some of the same issues as were seen in the trunk-chop wound, and my response to it was the same. The other wounds are covering adequately and require only patience on my part while the tree takes care of its business. It’s worth noting, as well, that the bark of red maple transitions as the tree ages. Although this young plant has smooth bark now, it will eventually feature rough textured, fissured bark, which should make these wounds much less noticeable:

Basal wounds, after

Some of the maple’s leaves had signs of a pest problem on their underside:

To me, the tiny globular appendages looked like spidermite eggs. Bonsai assistant Blaire examined them under a microscope, however, and based on Internet research thought they must be eggs of some other creature, although it is uncertain exactly what. In any event, the eggs were mostly open and no crawling creatures were seen. The tree had been treated with insecticide not long ago. The verdict is that there is no immediate threat, but the situation should be monitored in the days ahead.

This red maple is progressing well, albeit slowly. At this rate, the tree is not likely to reach a presentable stage of development before I retire. No matter. I’ve been enjoying the experience of growing it and feel content to leave it to someone else to eventually decide if it’s worth keeping in the collection or not.

February 2021

December 2021

July 2025

Postscript: The knock against red maples for bonsai use is that their leaves are too big. I’ve previously described how we deal with that. This picture shows the current state of foliage on our “Wounded Rider” red maple, and I think it makes a pretty good case for our method: