The Long Way Home

In a previous entry, I wrote about a man named Kent Kise from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who donated two bonsai to the Arboretum collection. Kent actually gave us three trees, and this entry concerns that third specimen.

I was at Kent’s house, looking at a selection of trees he had presented to me as possible donations. Two of the bonsai — a Japanese maple (Acer palmatum) and a European black pine (Pinus nigra) — stood out as the cream of the crop. When I indicated to Kent that the Arboretum would be pleased to have those particular trees he cheerfully agreed to give them to us. Then he gave a pleasant smile and told me there was a third tree he’d like us to have, motioning to it on the bench. Of the six or seven trees Kent had rounded up for our consideration, the one at which he now pointed was easily the least impressive. It was another pine, a Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii) by the looks of it, wildly overgrown and terribly leggy. The tree was big, fairly healthy and looked like it had been around awhile, but it had long grown out of whatever styling it may have once had. I didn’t see anything to recommend it. “Kent,” I said, “that pine looks like a project, and I’m not in position to take on any new projects. I’ve got my hands full. Besides, we already have several Japanese black pines in the collection and they’re all further along than this one is.” Kent raised his eyebrows and said, “But it’s not a Japanese black pine. It’s a Japanese red pine!”

I looked again at the tree. Not having much familiarity with Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora) because we didn’t have one in the collection, I wasn’t in a position to argue the point and I didn’t want to argue with Kent anyway. Whatever kind of pine it was, I didn’t think it had much to offer. I tried again to decline. Kent looked at me, cocked his head a little to one side and grinned earnestly. “I’d really like you to consider taking this tree, along with the other two,” he said. Kent was such a smooth salesman. The other two bonsai were attractive additions to the collection, desirable enough that it didn’t seem worth the trouble to quibble with the man who was offering to give them to us. If it would make Kent happy to have the Arboretum take the rangy pine into the bargain, I couldn’t think of a good reason to say no. After all, we didn’t have a red pine bonsai and now maybe we would.

Once the three donated trees were at the Arboretum, I made a documentary photograph of each. Here is what the bonsai I tried to refuse looked like when we received it in October of 2008:

October 2008

Telling Kent I wasn’t in a position to take on any new projects wasn’t a lie. I had no time to give this overgrown pine, so I stuck it out in the hoop house and didn’t do much with it. I saw the tree on a regular basis, though, when I was watering or working on some other tree nearby. Upon closer inspection the pine was found to be not only overgrown and leggy, but also extensively marred by wire scars. When training wire is left on too long it begins to bite into the bark of the limb around which it is wrapped, and the longer the wire remains in place the deeper it will embed. There comes a point when the condition is so advanced the branch is ruined. Even after the wire is removed, an ugly spiraling scar remains, accompanied by a grotesque swelling that cannot be repaired. This pine had a great many branches in this condition. Whenever I looked at the poor tree I came to the conclusion it was hopeless as bonsai material.

Still, I kept looking at it. And perhaps because the pine seemed hopeless, I couldn’t help but think about what might be done with it. One day I decided to take a step in the direction of finding out by cutting away all parts of the tree that I thought to be unusable. Any branching that was ruined by wire scars was removed and leggy growth was strongly pruned back. This was the result:

August 2009

Father Flanagan, the founder of Boys Town, was known to proclaim, “There’s no such thing as a bad boy”. Among people who do bonsai there is a tendency to think, “There’s no such thing as a bad tree”. This despite the fact that the surest path to a good bonsai is to begin with the best material possible. There is some allure to the challenge of taking a sow’s ear and transforming it into a silk purse, and when I saw the pine stripped down to just what was still usable I started thinking about possibilities. No, it would never be a great bonsai, but that didn’t mean it couldn’t be made into something more appealing than what it was.

In spring of 2010 I was scheduled to make another trip back to Pennsylvania, to do a demonstration program for a combined meeting of the Susquehanna and Lancaster bonsai clubs. I knew Kent would be there and thought it would be a nice gesture to use the difficult pine he had given us as the subject of the demonstration. I also took the occasion to let Kent know, in private, that I had looked into the question of exactly what kind of pine it was. “Kent,” I said, “when you donated this tree you said you thought it was a Japanese red pine, but I don’t think it is.” His eyes widened in surprise. “No?” he said. “What kind of pine is it?” I told him I was pretty sure the tree was Japanese black pine. Kent looked thoughtful for a moment, then broke into a delighted smile and said, “I always wanted a Japanese black pine!”

Here is what the tree looked like after the demonstration:

April 2010

The demonstration program was lively and fun for everyone, and Kent was pleased with the outcome of the styling work. I was satisfied enough with what was accomplished, but I knew I hadn’t found the tree yet. That is to say, a step had been taken but there would be more to follow. One of the aspects of bonsai I’ve come to most appreciate is that it lends itself so well to a process of creating through experimentation and discovery. It’s a cliché these days to say that the journey matters more than the destination, but I’ve always found the act of doing bonsai to be precisely so.

Although the pine was now more coherently organized in its structure, it was still too tall and had a visually unbalanced feeling. The more I looked at the tree the more certain I felt that the top had to be lowered further still. Just a few months later the deed was done:

July 2010

It had taken nearly two years to get to the point where the tree was reduced to a manageable size and left with only the parts necessary to build an acceptable bonsai. This work could have been done much faster, but there was no need to rush. The pine itself was in no hurry and neither was I. The Arboretum had many other more developed specimens we could use to fill the display tables at the bonsai garden and figuring out this tree was not a high priority. There was little expectation and no deadline.

The next three images depict the pine’s slow but steady development over the next three years:

October 2011

April 2012

February 2013

A series of four photos, presenting for the first time an in-the-round view of the pine, was made late in 2014:

October 2014

There is an old saying that familiarity breeds contempt. That seems a bit harsh, but without a doubt, familiarity allows for finding faults. This black pine that masqueraded for awhile as a red pine, and was correctly identified as a long-range project the first time I laid eyes on it, had plenty of aesthetic problems. Every time I worked with the tree, which was roughly once a year, I tried to make adjustments to mitigate aspects of the composition I thought to be flawed. At the end of each work session I’d feel like some progress had been made, yet a fully realized design for this tree always seemed to be far off.

Then in 2016, compelled by a feeling that it was time to push the matter, the pine was once more stripped down to bare essentials. Here is another in-the-round set of images to show the effect:

April 2016

The work done in 2016 was extreme, and the results were strange. I recall that particular year as one of general upheaval and personal difficulty. Those circumstances may have forced the issue, but perhaps it was simply time to put this specimen to the test in order to find out if it was ever to amount to anything. The severe cutting back was impulsive to the extent that I finally picked up the cutters and did what needed doing. Those removals, however, were the end result of much time spent looking and thinking, and there was nothing arbitrary about them. I took away all the parts I thought were wrong. The remaining parts, as can be seen in the pictures, made for one-sided tree. I didn’t want a one-sided tree, so now the job became figuring out a way to make the pine full again.

The work was slow. It could proceed no faster than the tree’s ability to generate new growth. No pictures were made along the way, so the next available look at the pine’s progress are these two images of opposite sides made five years after the severe cut-back:

January 2021

January 2021

As a side note, I am sometimes questioned on the practice of wiring the tips of pine branches to face strongly downward, as seen in the above images. At the Arboretum we wire pines in the winter because that’s when we have the time to do it, so we anticipate new growth in the spring. When that new growth occurs in the form of extending candles (a term used to describe a phase of bud development in pines), it immediately orients itself to the sun. That is, the growth will go upwards regardless of how the branch that holds the new growth is arranged. The end result makes the foliage look “right” while also contributing over the long term to the development of movement in the branching.

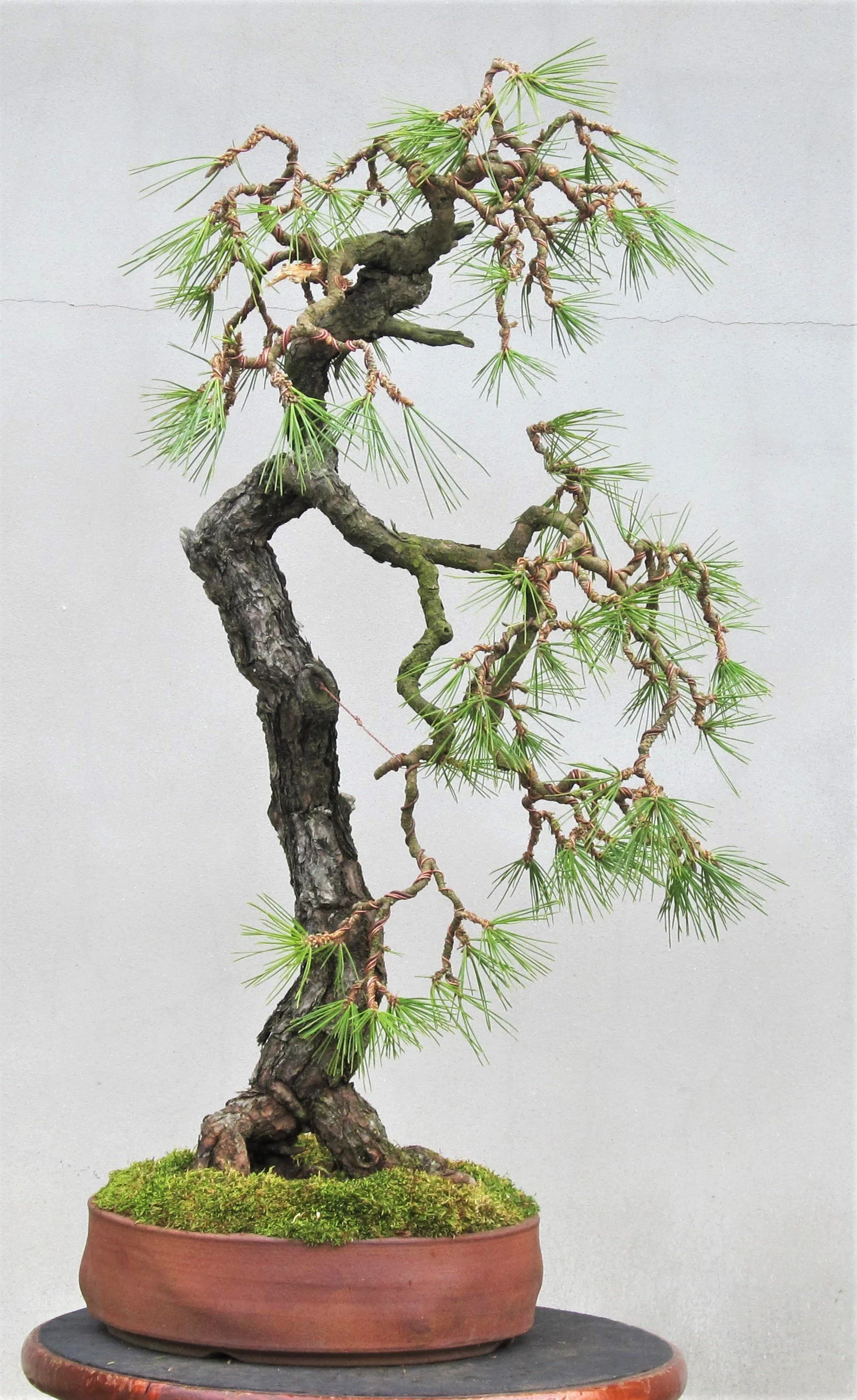

Kent Kise’s red pine/black pine is the subject of this week’s entry because it was recently given its late winter preparatory treatment in anticipation of a new growing season. I think this specimen has at long last found itself, or at least has arrived at a form I can finally accept. Bonsai are never finished until they die. From here on, however, my work with this tree will consist of tweaks and adjustments; no more stripping down. The container for this tree was made by Ron Lang:

March 2025

In conclusion, the following gallery tracks the development of this Japanese black pine over the twenty seven years of its life as part of the Arboretum collection (click on any image for full view):