Going Places

At the very beginning of 1993, work was underway on the reclamation of the donated collection that started the Arboretum's bonsai enterprise. I had come to terms with the idea that at least some of my work time would hereafter be dedicated to taking care of little trees and I was starting to learn how to do that. Don Torppa, the consultant hired by the Arboretum to evaluate the donated collection and bring it back under some sort of control, was also tasked with helping me get a handle on bonsai cultivation and design. I learned a lot from him, but Don was formulating a plan to have me further my education by studying with a well-known bonsai professional who was a friend and associate of his. When my horticultural mentor Dr. Creech caught wind of this he immediately stepped in and made arrangements for me to go to Washington DC, to study with bonsai curator Bob Drechsler. Dr. Creech was insistent that this be done and he pulled all the strings to make it happen.

Five days of bonsai study really isn't very much, however intensive the study might be. In the stage of development I was at, however, that period of time I spent at the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum was enough to give me a glimpse of a whole world of previously unimagined possibility. Originally I had known bonsai only as a strange thing people did with plants, and then I came in contact with some of the people who did bonsai as a pastime. Going to the Museum, which is part of the US National Arboretum, put me in contact with people who did bonsai professionally, at a much higher level. The quality of the specimens in the Museum collection opened my eyes as to what was possible with bonsai. The people I met at the Museum, the professionals and the volunteers who helped them, gave me an idea of what it might be like if bonsai were to become important at the arboretum where I worked. Such a situation was difficult to visualize before my study trip to Washington. For many years afterward, what I witnessed at the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum served as a template for the program I was striving to build. The curator, Bob Drechsler, and his assistant, Dan Chiplis, both knew I was a rank novice but treated me as a colleague. Their generous cordiality made me feel good about the prospect of being a bonsai professional. The Museum volunteers were all pleasant with me, but I hit it off particularly well with one of them, an older woman named Janet Lanman. It is difficult to explain why we find almost instant rapport with some people, but it was like that for Janet and me. She was intelligent, cultured and well-traveled, and she was tied into the higher levels of the bonsai world in the United States. Janet knew Dr. Creech, of course, but she was also a close personal friend of Yuji Yoshimura, one of the two biggest names in American bonsai at that time. This would later prove to be consequential.

There was another aspect of the study trip to Washington in 1993 that was formative: I spent my overnights as a guest in someone's home. My hosts in this instance were Skip and Marlese March, whom I had never met prior to spending a week as their houseguest. But they knew Dr. Creech from his days as the Director of the US National Arboretum, and his recommendation of me was all that was needed for them to open their door. It was personally challenging for me to do this. I never before had to navigate a social arrangement of this sort, and I am not by nature a particularly outgoing person. I was there, however, not simply as a fellow friend of Dr. Creech, but as a representative of The North Carolina Arboretum. In that role I was even more motivated to make a good impression by being on my best behavior. This same scenario, where I was placed in the intimate social situation of staying in the home of people who were otherwise strangers to me, would play out time and time again in the coming decades. I became comfortable with it and met some wonderful friends along the way.

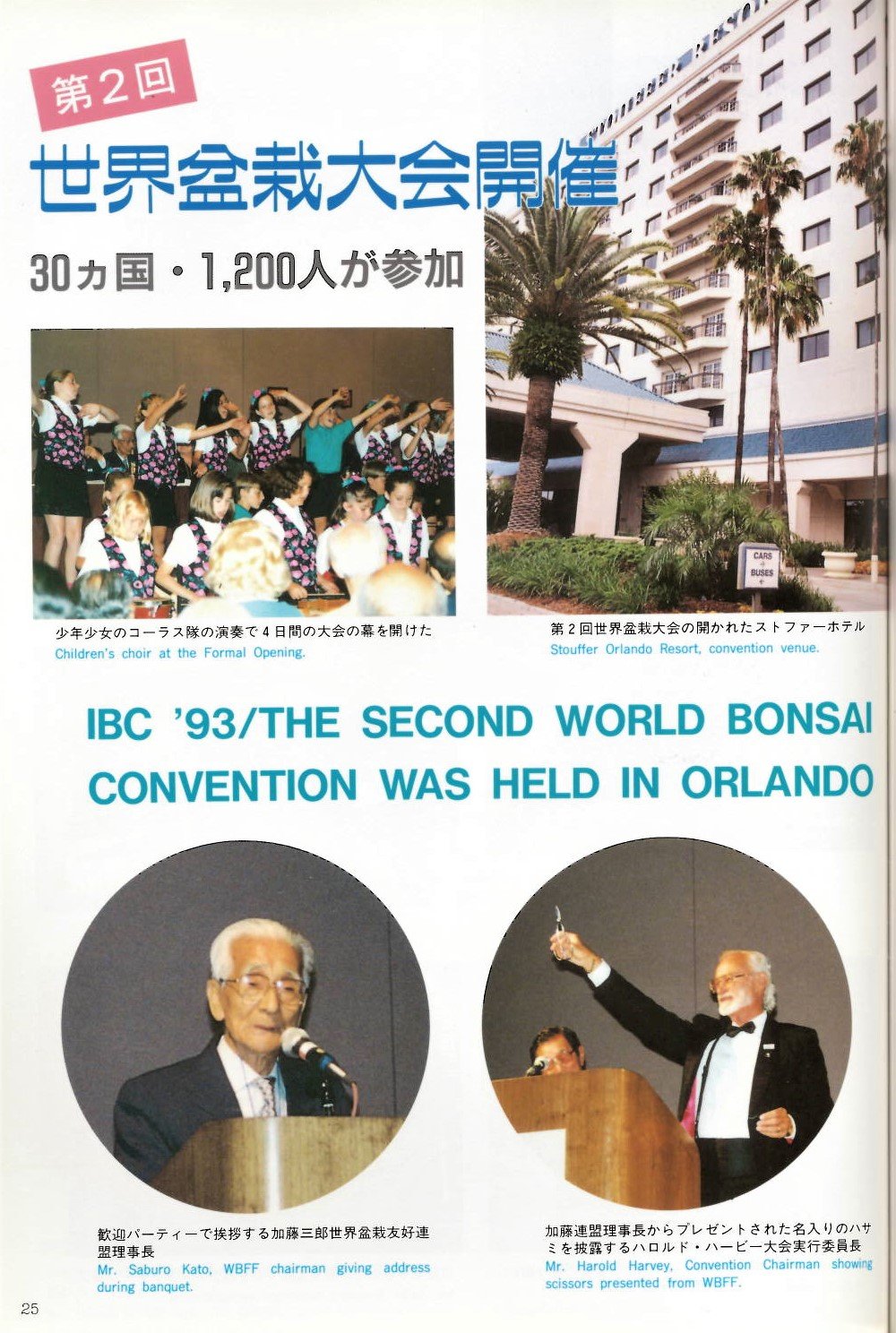

Another opportunity for work travel presented itself soon after, just a month following the study trip to Washington. The second World Bonsai Convention was held in Orlando, Florida, in late May of 1993, and the Arboretum sent me to attend it. This was the first bonsai convention I had ever been to, and I found the experience to be an exhausting mix of things both attractive and repulsive.

The bonsai element of the convention was a continuation of my education in the field of miniature trees. There was a large display of bonsai as part of the event, most of the trees provided by people who were members of the various clubs belonging to an umbrella organization known as the Bonsai Societies of Florida. At the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum I had seen my first public bonsai collection, and now I had an opportunity to see a large number of impressive, privately owned specimens gathered together in one place for a big show. Not surprisingly given the venue, there were many tropical species represented, plus a whole section dedicated to collected baldcypress. I was impressed by it all, but I was also looking at the displays with a critical eye. I had already been taught to do this as a means of developing my bonsai design skills. I didn't know much at this point, but I knew that bonsai were supposed to have a certain look and those that didn't have that look had something wrong with them and it was my job to figure out how to fix them. It was way too soon for me to question the idea of all bonsai needing to conform to a certain aesthetic standard, or to wonder where that idea might have originated.

The other primary element of the convention were the people in attendance. I am fairly certain the whole concept of conventions was invented by extroverts, primarily for the benefit of other extroverts. Conventions are social functions organized around whatever activity is the focus of interest, but the heart of the matter is socialization. Depending on your personality type, you are likely to find conventions either excitingly stimulating or emotionally draining. I find them difficult. Fortunately for me, Bob, Dan, and Janet from the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum were also in attendance at this convention, and their presence provided some welcome familiarity. Bob took me around and introduced me to many of the important bonsai big shots, telling them I was the curator of a new public collection. A number of these people I would encounter again in the years ahead and there were a few I would eventually come to know well. Reconnecting at the convention with the good folks from Washington meant a lot. Left on my own I probably would have spent more time hidden in my hotel room rather than making myself mingle in the large, boisterous and unfamiliar crowd. As it was, I still retreated to my room sometimes for badly needed solitude.

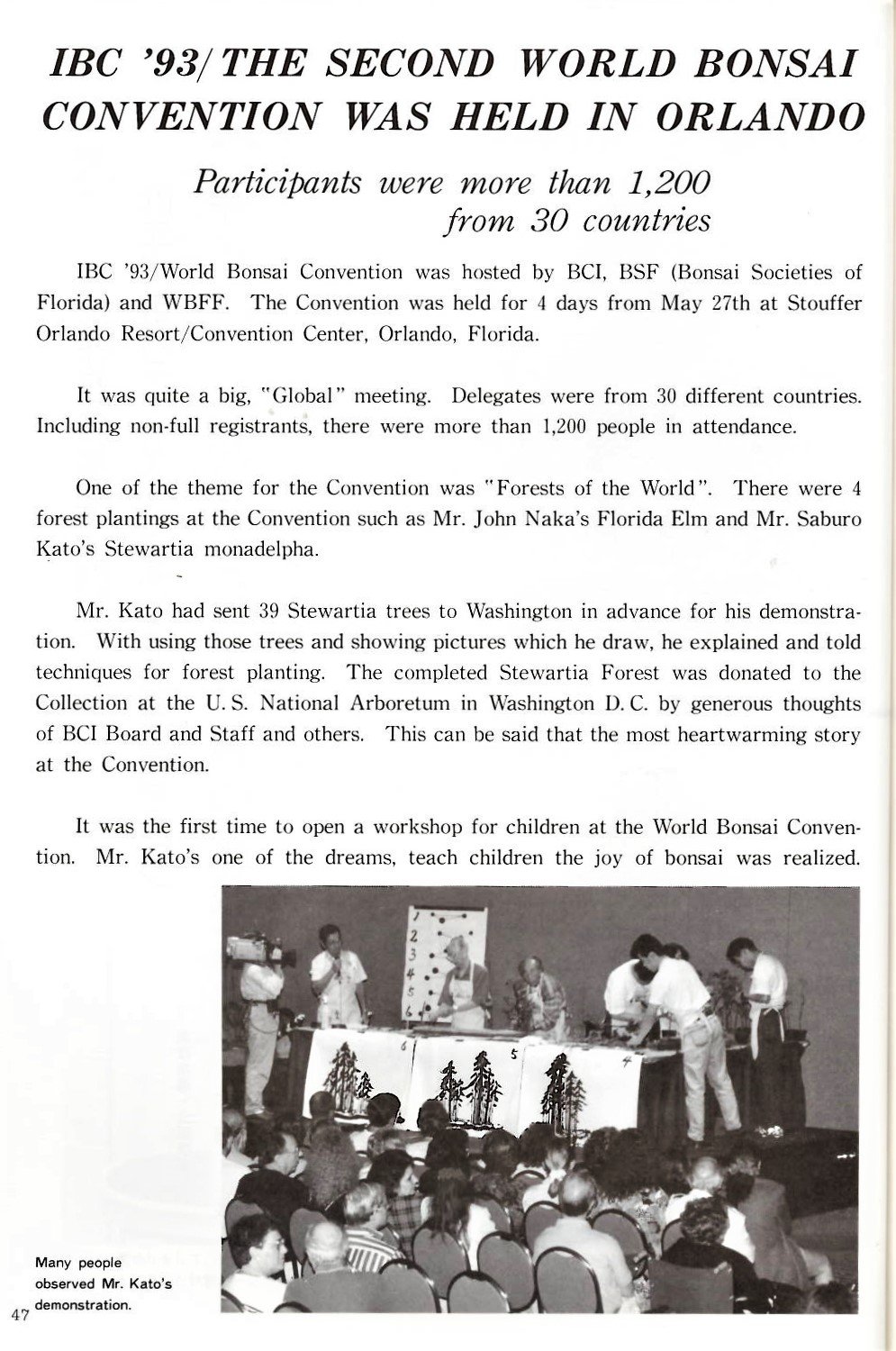

One of the main activities of any bonsai gathering is watching demonstrations. Prior to the 1993 World Bonsai Convention I had never seen such a thing, but during the course of that event I sat through at least a half dozen of them. The invited presenters at that prestigious event were some of the biggest names in bonsai, drawn from not only the United States but also Japan, China and Europe. It was obvious that much preparation had gone into these programs. The work was executed with great efficiency, usually by teams of helpers operating at the direction of the guest artist who was the star of the show. I was watching with the hope of learning some potentially useful technical information, but realized after a while that what I was witnessing was more like a peculiar form of performance art. People were there to see a show and the various presenters gave the audience what it was there to see. Some of the artists, like Suburo Kato from Japan or John Naka from California, were obviously held in great veneration by the attendees, so their every move on stage was received with rapt appreciation. The verdict at the end of each presentation was that the demonstration had been wonderful and a new masterpiece had been created right before our eyes.

All this was fascinating to observe because it was all new to me. My bonsai concept had once again been enlarged. Now I knew that bonsai was a strange thing people did with plants; that there were hobbyists who were seriously dedicated to bonsai; that there were professionals who managed to make a living doing bonsai; and that these two groups interacted in a symbiotic manner, often at conventions and other organized bonsai gatherings. Given all that, there is another aspect of bonsai culture that was inevitable, but still somehow came as a surprise to me. Like any other activity involving people, the world of miniature trees is full of politics.