The Wounded Rider - Part 2

Dieback happens and you usually don't have to guess at the cause of it. The necrosis on one side of the root-over-rock red maple, running up one of its surface roots and extending into the trunk, materialized without any clear provocation — it just showed up. It was yet another disappointment for this specimen, the latest in a series of setbacks that started twenty years earlier. Maybe this tree didn't want to be a bonsai.

I put the red maple aside for a while. I'd see it now and then when I was working in the hoop house, and I'd look at it and wonder if there was any way to get around the problem. As time went along the depressed area where the damage was became ever more noticeable.

A natural tendency toward obstinacy was only one factor in my inability to let go of the maple and put the sorry tale down to experience. While I was fumbling around with all the difficulties caused by the bifurcated root structure, I was having much more success in shaping the upper portion of the tree into an agreeable arrangement. Perhaps because the whole project had a feeling of experimentalism to it, I had been working the branching of the tree in a very loose and improvisational manner. This maple was one of my earliest efforts at naturalistic styling and I was pleased with its progression in that regard. The successful development of the crown gave me reason to persist in trying to get the rest of the tree sorted out.

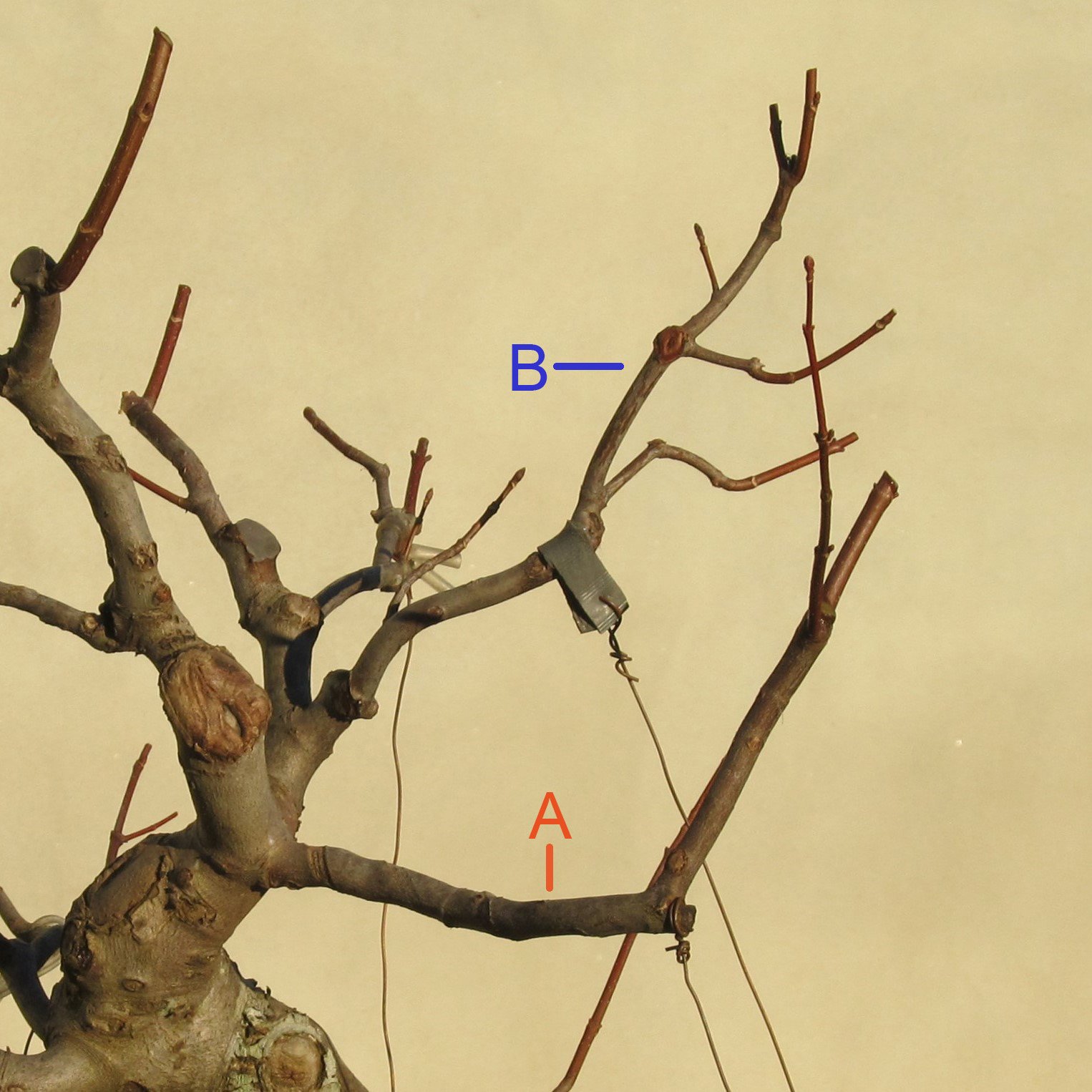

The following is an example of how the shape of this maple's crown evolved. Looking at one isolated section of the branch structure we see the effect of two years of growth and developmental training (click on either image for larger view):

The branch labeled "A" was one initially thought to be important to the overall design of the crown. It was the lowest branch on that side of the tree, with the intended function of providing a big portion of a wide spreading canopy. For whatever reason, that branch was slower to develop than any other on the tree and remained leggy and awkward in appearance, despite my best efforts to invigorate it.

In contrast, the branch labeled "B", on the same side as branch "A", grew with great vigor. In a period of two years that branch produced numerous secondary branches and increased its girth to a point where it was, from a compositional perspective, too strong for where it was situated.

The intensive styling session that occured at the end of the 2015 growing season addressed both issues:

The solution to the dilemma posed by the spindly nature of branch "A" was to remove it. The decision wasn't impulsive or lightly considered. A reassessment of the existing branch structure resulted in an adjustment to the design that made branch "A" expendable. When working with living plant material there is good reason to be flexible in your thinking.

The handling of branch "B" was in line with standard bonsai practice, wherein a part of the tree that exhibits too much strength is checked by means of assertive pruning. A large section of an overgrown branch might be removed, cutting back to a secondary branch which is then trained to take over as the continuation of the primary branch line. The ideal end result of this technique is not only to make the branch shorter but to build a branch line that has movement and taper and doesn't look like it was pruned. In contrast, branch "B" was shortened by breaking it and making no attempt to disguise that the branch line had been truncated by damage. The placement of the breakage was not arbitrary. It was done at a location where there were two existing secondary branches of different diameter, which were then trained to look like they were the survivors of a violent incident. The formation is not uncommon in nature as damage to tree limbs is always happening:

Therein lies the crux of naturalistic bonsai styling: Observe trees in nature and study how they are shaped, then apply those lessons to the shaping of bonsai. There is a mindset that develops if you follow the naturalistic path long enough, one that thinks in terms of cause and effect. What caused the damage to branch "B"? In reality it was a person snapping the limb to shorten it. In the imagined story it could have been caused by any number of stimuli, but the more important part of the equation is what the tree does in response to the damage — what the effect of it is. The branch sustains damage, then the tree responds in a way that isolates the damage and allows the tree to continue the business of living.

What caused the damage to the trunk and exposed root of the red maple on the rock? In reality I have no idea. In imagination it might be plausibly explained by a few different possible story lines, but the important aspect remains what the tree does in response. If such an injury occurred in nature the tree would respond by isolating the damage and then carrying on with the business of living.

Here is a suggestive story of how it went: A tree up on a rugged mountain top started life as seedling growing in a little pocket of organic matter collected in a depression on a rock. Sensing the limitations of the space in which it grew, the tree sent out roots trying to find the way to more growing room. Some of those roots made it into the earth at the base of the rock and found new freedom, which allowed them to grow and increase in girth. After awhile it appeared as if the tree was sitting astride the rock, roots like legs dangling down to the ground. Meanwhile, life was challenging for the tree in other ways too. The wind was always tearing at it, and snow load sometimes broke branches. The tree could never grow straight because the harsh environment was always presenting obstacles, so the tree survived in a cycle of constant damage and recovery. One particularly bad night a nearby tree fell and scraped a big swath of bark from the flank of the tree on the rock, leaving it raw and exposed. Insects and rot subsequently entered the body of the tree through this wound, but the tree defended itself with a chemical barrier, erected as an emergency response to check the invasion and isolate the damage. A portion of the trunk was hollowed out in the process, but ultimately the damage was contained by the efforts of the tree. A large opening remained as a lasting wound, but the integrity of the tree was maintained. The struggle to survive continues.

Here is the definitive story of how it went: After a long series of misadventures that finally produced acceptable results, something unknown happened to cause dieback on the flank of the little root-over-rock red maple bonsai. In response, in spring of 2018 I took an electric rotary carving tool and opened up the area where the necrosis occurred, carefully shaping the wound to make it look like rot had made some headway into the body of the tree before it was checked by the tree's natural defenses. With the tool I gave the upper end of the wound the appearance of a hollow in the root line leading up to the trunk, although just out of the viewer's sight the carving comes to an end and the wood of the tree remains intact. The lower portion of the wound was tapered in a way that would allow water to drain out. The exposed wood was then charred with a torch, abraded with a wire brush and finally treated with wood hardener. The end result looked like this:

2018

I have to admit, I would never have chosen to open up a big hole on the side of this bonsai for the sake of giving it greater character. Misfortune paid a visit, though, creating a situation that called for a response. The only decision before me was whether to give up on the tree or accept what had happened and make the best of it.

I chose to keep going. I thought about cause and effect and tried to follow the storyline, imitating the natural example but speeding up the process. How might a tree in nature respond to such an injury and how might the affected part of the tree look several decades later? Make it look like that.

By summer of 2021 the maple on the rock was on display in the bonsai garden:

2022 was a banner year for this specimen. It had never looked better and so it remained on display in the garden for the entire growing season (click on any image for larger view):

The poetic name The Wounded Rider was bestowed upon this tree, partly as a nod to the joke my friend David had made years before. There is no missing the resemblance to a human torso and legs once you see it. In fact, I think this particular bonsai is as anthropomorphic in its overall appearance as any we have, and that characteristic is compelling in any tree big or small. There is something that can be mysteriously unsettling about a tree that looks human in its form, too. The name for this piece is meant to enhance that sensation.

Below is a comparison of the carved area on the side of The Wounded Rider, showing how it has changed in five years' time. Note the thick callous rolling in on all sides of the wound (click on either image for larger view):

The following images show the present condition of the grafted third root. It is should be remembered that the bark of this specimen, although smooth now, will eventually be dark in color, featuring long, rough-textured plates. By the time that happens the graft union should be much more difficult to see. The view on the right shows both the wound and the grafted third root — certainly not the most favorable way to look at this bonsai!

2023

2023

A fourteen-year developmental progression in four images: