Crazy Horse

Common plant names are often misleading. A case in point is a tree species widely distributed throughout Eastern North America and commonly called Eastern redcedar. The scientific name for this species is Juniperus virginiana, which correctly identifies the tree as a juniper. The system of scientific naming (binomial nomenclature) was invented so a plant, or any other living organism known to exist, can be referred to by a name that accurately describes it based on its genus and species. Scientific names are consistent and applicable anywhere in the world, regardless of what any given creature might be called locally.

Eastern Redcedar (Juniperus virginiana)

It is worth taking a moment to note the redcedar is actually a juniper because junipers are typically thought of as good plants for bonsai use, while redcedars are typically not. Look through any bonsai collection and you are likely to find at least one or two juniper specimens, usually Asian species and their cultivars, and any bonsai book or website will extol juniper's virtues. Go looking for established redcedar bonsai specimens and you will likely not find any. The same search for bonsai junipers will almost certainly turn up examples of a different North American juniper species that has found favor — the Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum). Curiously, Rocky Mountain juniper is thought to be very similar to Eastern redcedar. The natural range of distribution for Rocky Mountain juniper takes up roughly where Eastern redcedar leaves off, so they might be thought of as the eastern and western versions of a tree form of juniper. According to the US Department of Agriculture, the two species even self-hybridize where the boundaries of their range meet.

Why is Rocky Mountain juniper embraced as a bonsai subject while the very similar Eastern redcedar is shunned? The main reason is that incredibly old, gnarly, stunted Rocky Mountain junipers are collected from high elevations out west and these have proven irresistible to bonsai enthusiasts. They are bought and sold for substantial sums of money. When it comes to a genuinely old tree, most bonsai growers are willing to overlook difficulties like coarse foliage and growth habit, traits common to both Rocky Mountain juniper and Eastern redcedar. The appeal of agedness in bonsai is so great that some people even buy expensive collected Rocky Mountain junipers and then graft Shimpaku juniper (Juniperus chinensis 'Shimpaku') foliage onto the limbs of the old trees, in order to overcome what they see as the problem of less desirable Rocky Mountain juniper foliage. This practice takes years to produce results, but not nearly so many years as the centuries it took for the juniper collected from the wild to attain the aged appeal of its twisted trunk and limbs.

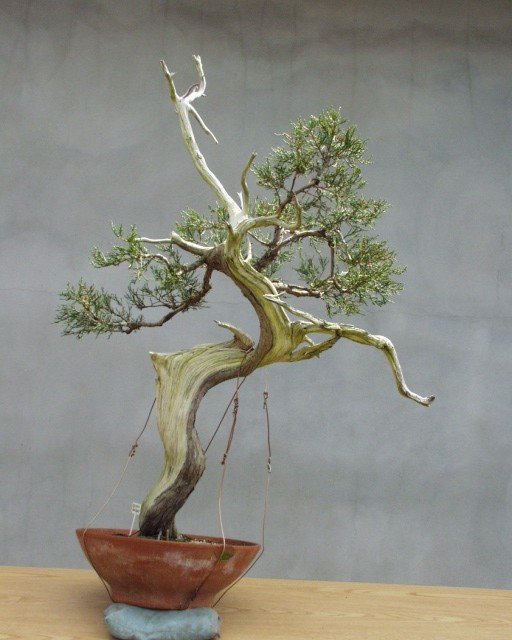

Few genuinely old Eastern redcedar have been collected and made into bonsai. As it happens, the North Carolina Arboretum bonsai collection has one:

This Eastern redcedar was collected by a local bonsai enthusiast from a high elevation site in Western North Carolina sometime in the mid-1990s. This photograph shows the tree as it looked in its original location:

Remarkably, this specimen was not excavated. The tree's roots went down into a narrow crevice in solid rock, so the collector decided to take it by means of air-layering. To make an air-layer, a woody plant limb, or in this case the trunk somewhere above the base, is stripped of its bark in a wide ring that goes entirely around that member's circumference. Under other circumstances such a removal of the bark and tissue beneath it would result in the death of whatever part of the plant was so disconnected from the roots (a process known as girdling). However, in the air-layering technique the damaged area is treated with a rooting hormone and then packed in damp sphagnum and sealed in an enclosure that preserves the moisture. The part of the plant no longer connected to the roots will then produce roots of its own that emerge from the severed bark and work their way into the damp sphagnum to access the moisture. Once these roots emerge and enlarge sufficiently the part of the plant that has produced them can be detached from the rest of the plant and potted, to go on living as an independent individual plant with its own root system. Propagating by means of an air-layer is usually done in a single growing season. The air-layering of this old, slow growing Eastern redcedar took two years.

After having accomplished this amazing feat of collecting, including hauling the tree in its fragile condition down off the mountain, then successfully potting it up and keeping it alive for several years, the collector had second thoughts about how to go about making his prize into a bonsai. He spoke to me about it and I suggested he might donate his redcedar to the Arboretum. He demurred. Then I mentioned that Japanese bonsai master Susumu Nakamura was coming to Asheville to visit the Arboretum, and I suggested the possibility of Mr. Nakamura doing the initial styling of the tree. That is, if the redcedar was donated to the Arboretum's collection. This proposal had appeal and the donation was made.

Mr. Nakamura had been my teacher in Japan and had subsequently been the guest artist at the third Carolina Bonsai Expo in 1998. In August of 2000 he was scheduled for his annual visit to the Chicago Botanical Garden and I invited him to come to Asheville again while he was in the United States. During his visit to the Arboretum I gave him the redcedar to use in a styling demonstration, conducted exclusively for the donor and a small group of invited guests. Mr. Nakamura did not think much of the tree he was given to work on. Asked what he thought of Eastern redcedar, a species unfamiliar to him, he replied, "I hope I never work on another one!"

Mr. Nakamura in the Support Facility head-house, sketching the redcedar.

Mr. Nakamura’s design idea as he sketched it.

Mr. Susumu Nakamura with the Eastern redcedar after the design session.

Three main accomplishments came out of the session with Mr. Nakamura. First, the redcedar was growing in a large mica pot that he felt was not right for it. He transplanted the weakly-rooted tree into a much smaller terracotta pot, securing it with guy wires wrapped around the container. Mr. Nakamura also pruned a good deal of branching and foliage that he felt was excess, leaving what he anticipated might be useful but not making any effort really to style the tree. Finally, he chose what he felt was the best perspective on the tree, the view of it that would most likely be presented as the front. He made a large drawing of his design idea based on that view. These three outcomes were important steps toward the redcedar eventually becoming a bonsai, but that desired objective was still a long way off.

Here is a gallery of images showing the Eastern redcedar in November of 2003, more than three years after the styling session with Mr. Nakamura (click on any image for larger view):

The tree had not been repotted since the session in 2000, but it was still not strong in its roots. The rank growth of the branching and foliage had been brought somewhat under control entirely through the cut-and-grow method.

Here is an image from early in 2005:

At this point the tree had still not been repotted. Noticeable refinement had finally started to materialize in the crown.

The next available photograph of this specimen was not made until mid-2018, nearly eighteen years from the time Mr. Nakamura worked on it:

The long interval between photographs is testament to the fact that this Eastern redcedar grows at a painfully slow rate. Progress was being made, however, as witnessed by the tree now being planted in a high-quality bonsai container made by Robert Wallace. The foliage mass also exhibits much greater definition and refinement at this point. Note that the long, extending piece of deadwood that used to jut up from the top of the tree had been made much shorter. Note, too, that the extending deadwood piece that stuck out to the right side and then doubled back to the left had broken off, leaving just the half that pointed to the right. That piece was always frail and it finally broke off. I saved it though, and eventually reconnected it. The tree was changing but that change played out over such an extended period that I neglected to document it.

Not only did years pass without the redcedar being photographed, it had never in all the time we owned it been put on display. I always felt it was a good tree but needed work, and that way of thinking went on year after year. Most people didn't know the tree existed because it lived quietly out in the hoop house and no attention was called to it. In 2018, eighteen years after being received in donation, I decided the time had come for this specimen to have its public debut. For the sake of making a splash it was chosen to be the logo tree for the twenty-third Carolina Bonsai Expo.

This required some cosmetic work, but fortunately the redcedar cleaned up well. Here it is on display in the garden later that year:

As the Expo logo tree, a portrait was made of this fine old Eastern redcedar. Its time to shine had finally arrived:

I mentioned before about the piece of deadwood that broke off and was then reattached. I went through the trouble of doing that because the piece seemed important, but I took the opportunity to adjust it a bit. Originally the piece that broke doubled back on itself and crossed the sightline of the trunk when the tree was presented in the way that best displayed the impressive bulk of deadwood. The deadwood of the trunk is what makes this tree stand out. Having anything that obstructed the view of that feature was undesirable, so it didn't make sense to put the broken piece back the way it was. I repaired the break with a small wire inserted as a coupling mechanism and left the reconnected piece in a dangling position. I did it that way because I thought it looked good, but it turned out to have an unanticipated beneficial effect.

Here is a comparison of the repaired deadwood branch, as it was and as it was reformed:

2000

2018

2021

The unintended effect of the dangling branch revealed itself when I was making the Expo logo image. Suddenly what I saw before me took on a certain shape so clearly visible that once seen I couldn't un-see it. It was the image of a rearing horse:

This startling apparition led to the naming of this distinctive redcedar bonsai as Crazy Horse. That name is descriptive enough, just based on the uncanny resemblance of the deadwood of the tree to the image of a rearing horse, but the name of Crazy Horse has another potent meaning. The Crazy Horse of historical fame was a nineteenth-century warrior leader of the Oglala band of the Lakota tribe of American Indians. Often mistakenly identified as a Chief or Medicine Man, he was neither, but gained notoriety as a fearless leader and protector of his people. His name, properly translated, was more like His-Horse-Is-Crazy.

What does the historical figure named Crazy Horse have to do with Eastern redcedar bonsai? Nothing whatsoever, as far as I've been able to figure. I could say Juniperus virginiana is a tree species burdened with a misleading common name, and Crazy Horse was a famous member of a whole group of people — Indigenous Americans — likewise misleadingly labeled when referred to as Indians. But that isn’t how it happened. Crazy Horse is just a very cool name and our redcedar does look like a rearing horse!