Carolina Hemlock

Most folks don’t know Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana). One reason for this is that the tree has a very restricted range, naturally occurring only in some scattered parts of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Carolina hemlock is sometimes found in cultivated landscapes, but only rarely, and few nurseries offer it for sale.

The much better known hemlock in these parts is eastern, or Canada, hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). Of the two, eastern hemlock is not only far more numerous, it seems the superior species in many regards. Eastern hemlock can grow well over one hundred feet tall, while Carolina hemlock usually tops out at about fifty to seventy five feet. Eastern hemlock is a highly refined tree in its visual effect, often described as being graceful or even majestic in appearance. Carolina hemlock has a more rugged (or is it scruffy?) character, with a more prosaic effect in the landscape.

A Carolina hemlock alongside a trail in Pisgah National Forest

A stand of Carolina hemlock, thirty five to forty feet tall

Carolina hemlock bark is similar in appearance to eastern hemlock

One easily observable difference between the two hemlock species can be found in the foliage. The needles themselves look much the same, but how they are arrayed on the stem differs. Eastern hemlock needles are held out horizontally in flat sprays, while Carolina hemlock needles radiate outward from the stem in all directions. The result is that Carolina hemlock foliage has a fuller appearance, looking almost soft and cushy.

Carolina hemlock foliage

A Carolina hemlock planted at the Arboretum along Greenhouse Way. This tree has been in the ground for more than thirty years and has reached a height of about fifteen feet.

Because they are a rugged mountain species, Carolina hemlocks can sometimes be found growing at higher elevations. These trees can become quite picturesque under the right conditions. The following images offer three different perspectives on a wonderfully stressed-out but fiercely clinging to life Carolina hemlock specimen growing on an exposed rock outcrop at above five thousand feet elevation. The other needle evergreens growing alongside are all table mountain pines (Pinus pungens).

I’ve never come across an eastern hemlock growing in a similarly stunted, gnarly form under such harsh conditions. The fact that Carolina hemlock has the capacity to adapt itself to such circumstances offers a clue as to one particular way in which Carolina hemlock is superior to eastern hemlock: Carolina hemlock performs better as a bonsai.

That statement reflects my personal opinion, as derived from more than twenty years experience cultivating both species as bonsai subjects. The more full foliage effect of Carolina hemlock seems to play better at the smaller scale than does the flat foliage of eastern hemlock. More importantly, Carolina hemlock seems to adapt better to greater sun exposure, its foliage tending to grow only more full and dense. Eastern hemlocks can grow in the sun too, but they seemingly want to grow only upwards. The end result is that eastern hemlock bonsai needs to be wired nearly all the time. Freed from its training wire and growing in the sun, eastern hemlock immediately reverts to form and grows upward, spoiling whatever shape it’s been given.

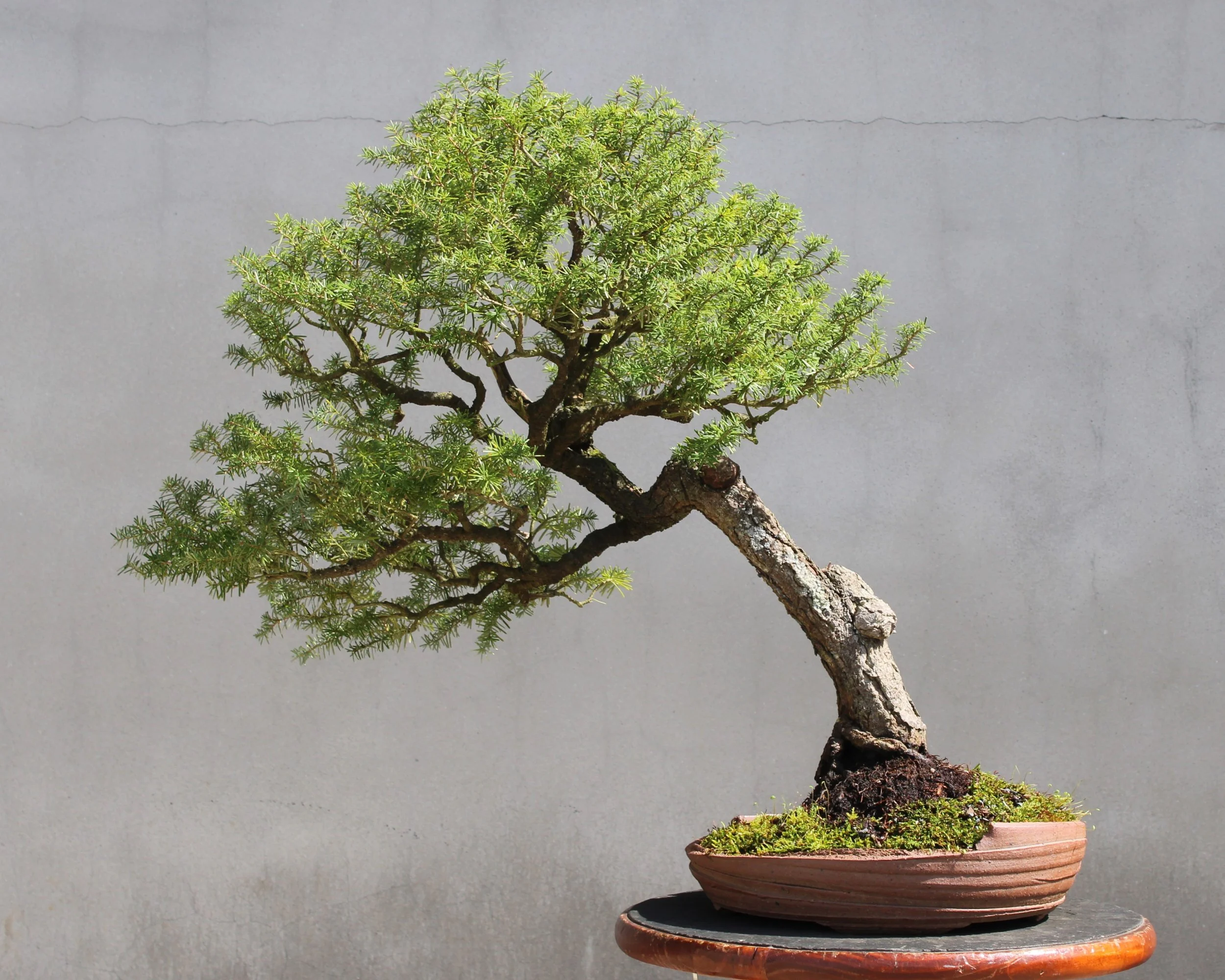

There are two Carolina hemlocks in the Arboretum bonsai collection. One is found as a member of a tray landscape previously featured in Curator’s Journal. The other is a stand-alone specimen and is the subject of this entry.

This Carolina hemlock came to us as a very young tree in a donation. The person who gave it to us had purchased the tree from Plant City Bonsai in Clermont, Georgia, then decided they didn’t like it once they brought it home. The tree was scruffy and not really trained, and had been collected from somewhere in nature. The appeal as a bonsai candidate was in its trunk, which had apparently been snapped off at some point in the tree’s life. The hemlock had recovered from this early injury and resumed growing in sprouting juvenile fashion. It’s a fair guess the plant had been sold as pre-bonsai material.

After arriving at the Arboretum, the Carolina hemlock was stationed out in the hoop house with a host of other project trees and allowed to grow strong and full. In 2007 I took this now leggy bush-on-a-stick to the Cullowhee Native Plant Conference in Sylva, North Carolina and used it for a demonstration.

This image from the following spring is the first we have of our Carolina hemlock:

March 2008

In a manner tried and true among people who attempt to make bonsai out of leggy material, the demonstration consisted of me cutting off the top of the tree and training what had been the lowest branch to take over as a new top. In the above photo, the old damaged area that had caused the tree to be considered for bonsai use in the first place can be seen on the lower left side of the trunk. It really wasn’t all that much to look at.

Four more years of the Carolina hemlock being grown as a back-bench project yielded this result:

April 2012

When you see a bonsai-in-training featuring a limb (in this case the upper trunk line) that sticks out noticeably and seems out of proportion to the rest of the tree, it’s almost certainly a sacrificial branch. Sacrificial branches are allowed to grow with little restraint for the purpose of enhancing the overall strength of the tree. As the name suggests, the ultimate fate of the proud member is to be cut off. The rest of the tree can be worked into shape as the sacrificial part extends, and then when the time is deemed right, the sacrifice is made and the tree moves forward in its design.

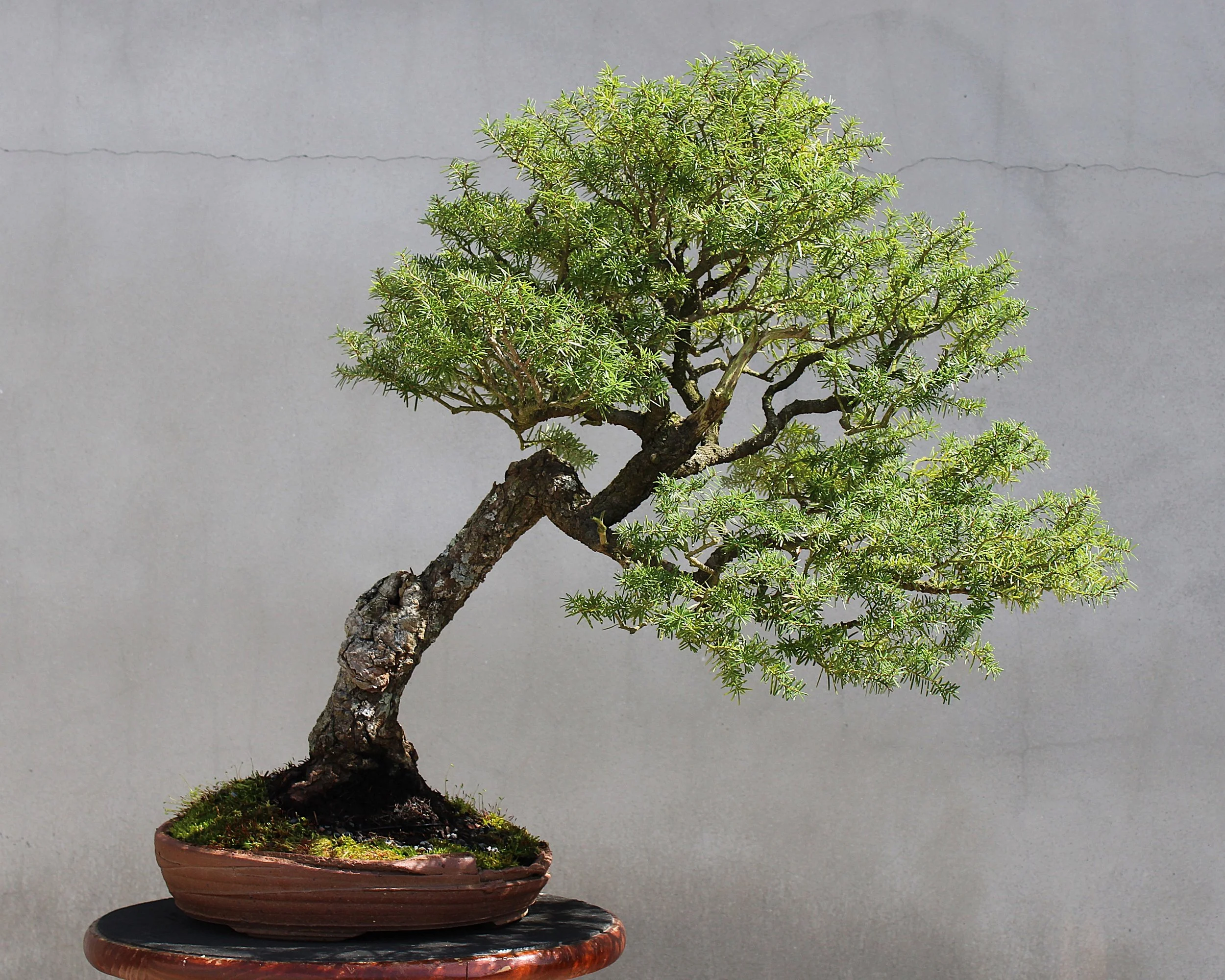

With our Carolina hemlock, that event happened in the winter of 2018. A sculpted dead staub was left where the pruning was done, incorporating the remains of a training technique into the suggested story of the specimen. At this point I felt the tree was showable and so it made its bonsai garden debut the following spring (notice the trunk-thickening that had occurred):

May 2019

The Carolina hemlock had been removed from its previous training pot and planted in a unique American-made container. The pot is the work of Brett Thomas from Pennsylvania.

Later that same year the tree exhibits fuller foliage:

August 2019

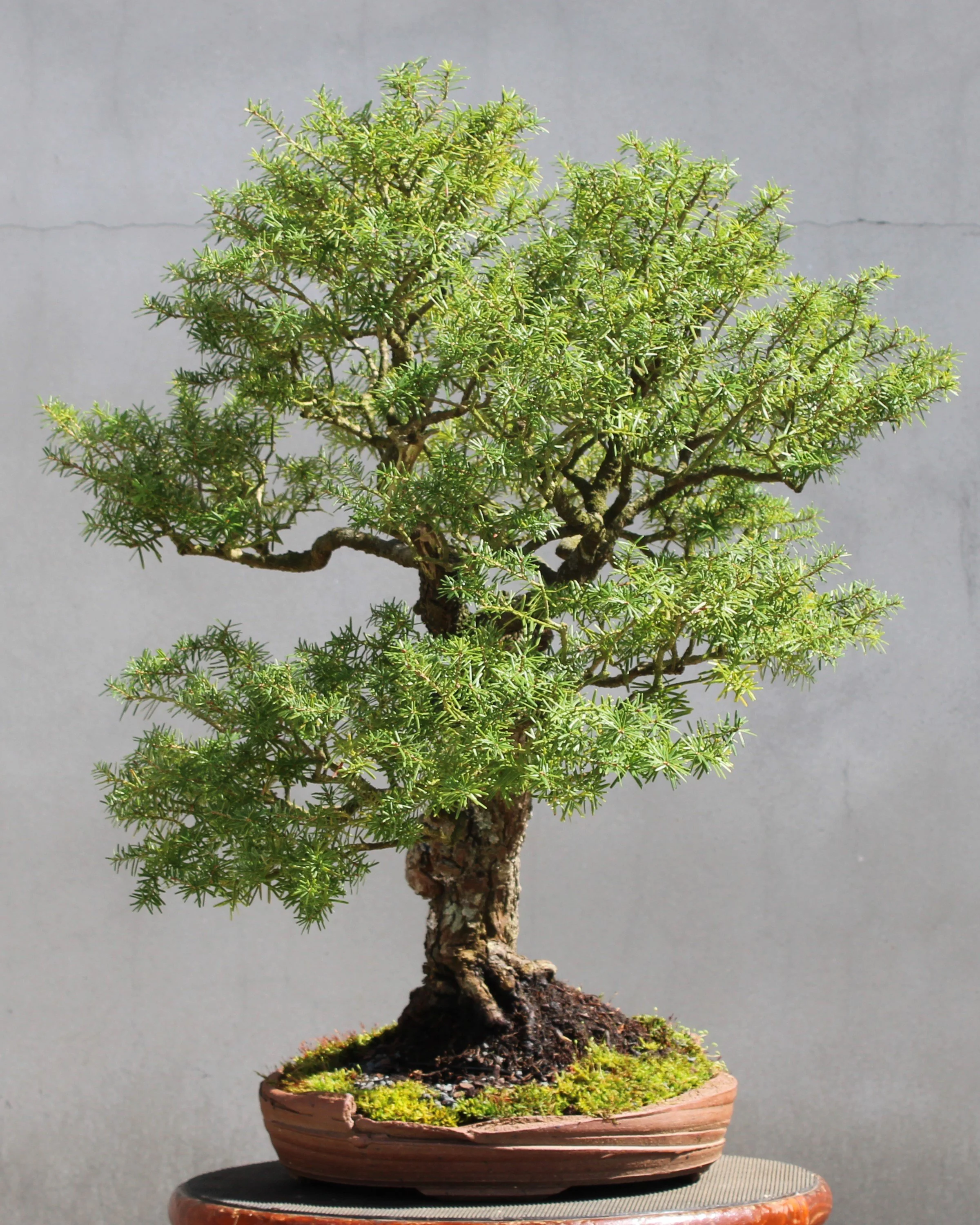

Another year of growth and development and the Carolina hemlock looked like this:

October 2020

As each year passes, the crown of the hemlock becomes more detailed in structure, while the tree’s trunk takes on a more aged appearance and begins to host lichens:

September 2021

The above image inspired the logo for the second year of Curator’s Journal:

Each year in late winter or early spring, the hemlock is pruned and cleaned up in advance of a new growing season. When pruning at this time I cut back only so far as the presence of buds allows. As long as a stem is cut back to an existing bud it is almost certain to live and grow. The buds on this Carolina hemlock can be tiny, so a careful reading of each stem is necessary. When pruning woody branches I always cut back to an existing side branch. Hard pruning that leaves a branch devoid of any foliage will result in a dead branch. Later, during the growing season, this tree is pruned by pinching out the centers of extending shoots while they are still soft. The shoots are allowed to come out and retain some of what they have produced, but are not allowed to grow as long as they otherwise would. This technique checks the shoot extension and also stimulates back-budding. The result is a more dense and compact crown.

In spring of 2025 the Carolina hemlock received its customary preparatory attention and the result was recorded in a series of four images. Each photo shows a perspective of the tree one-quarter turn clockwise from the preceding view. This allows us to see for the first time what this specimen looks like from an angle other than the preferred view that has thus fare been shown:

March 2025

March 2025

March 2025

March 2025

This hemlock has sometimes been shown with its “B” side forward facing, rotated 180-degrees from the usual preferred viewing angle. This view is the complimentary opposite of the preferred view and therefore not substantially different. The two “side” views are much weaker aesthetically, in my opinion, and the hemlock is never displayed that way. Still, it’s interesting to note that when viewed from the side the hemlock is revealed to have a bifurcated trunk line in its crown. There is no law against this, although most bonsai growers shy away from giving their little trees this sort of structure. In this instance, the dual trunk line is actually a primary reason why the tree can be shown effectively from both “front” and “back” — the resulting crown has a full and rounded shape. Too many bonsai have pointy heads!

May 2025

Here is a side-by-side comparison of how it began and how it’s going:

2008

2025