A Craggy Little Elm

The Arboretum’s bonsai collection doesn’t include any true miniatures. We do have a few trees that can be easily carried in the palm of one hand, but we don’t have any of the dramatically small bonsai that can be held with a few fingers. Those sort of trees are a tremendous amount of work! Tiny bonsai, I think, would also tend to get lost in the scale of our bonsai garden presentation, a consideration that carries a lot of weight.

Still, we have some smaller size bonsai and they serve us well. When making a presentation of bonsai, which is what the Bonsai Exhibition Garden is, it is useful to have a range of tree sizes. Variance in height is one of the components necessary in creating a visually engaging display.

Among our smaller sized trees is one cork-bark Chinese elm (Ulmus parvifolia ‘Corticosa’) that stands about fourteen inches from base to tip. It’s not the bonsai most likely to attract attention or be remembered and talked about later on, yet this little elm spends most of every growing season on display in the garden:

Part of the reason I favor this little tree has to do with the aforementioned desirability of manipulating height differential when constructing a bonsai display. There’s utility in its diminutive stature. Beyond that, however, I appreciate this tree for its naturalistic structure and for what it has taught me in the years I’ve been working with it.

Sometime back toward the end of the last century, I struck a couple dozen cork-bark Chinese elm cuttings which compliantly grew roots and became little trees. Many of these were subsequently used in the creation of a tray landscape (previously featured in an early Journal entry). The remaining elms were grown on individually. One day early in the current century, I was out in the hoop house spending time with the plants and came across one of those leftover elms. I examined the little tree and saw nothing good about it, at least not from my biased and self-serving perspective of assessing bonsai potential. Being a Chinese elm, the little tree automatically had something in its favor because there are few deciduous tree species in the world that better lend themselves to bonsai than Ulmus parvifolia. We had plenty of Chinese elms, though, so I was looking for some other mark of distinction. I couldn’t find any. The tree had some weak little bit of movement in its trunk down near the base and then a long stretch of trunk sticking straight up, without movement or taper. The elm was very young and I was looking at it more critically than I perhaps should have been.

Who knows why, but on that particular day when I decided this little stick-in-a-pot elm didn’t have the right stuff, I impulsively reached down and grabbed the long, straight trunk and snapped it with my two hands. It could be that I have a darkly violent impulse buried deep in my psyche that happened to flare up in that moment, venting itself on a poor, defenseless plant that had the misfortune of being nearby, but I’d like to think otherwise. I’d like to think I was testing a theory I’d been formulating.

I had begun looking at trees in nature and pondering how they came to be shaped the way they are. I was thinking broadly of trees as living organisms and the many factors — genetic and environmental — that through combined effect give trees shape. It did not take long to recognize that many trees, especially older trees, show signs of damage and recovery. That is, something untoward happens to affect the intended growth of the tree and the tree then has to make what repairs it can in order to carry on its business. Sometimes the damage incurred is small and the resulting alteration in the tree’s shape is minimal. Sometimes the damage is catastrophic and the result is a dramatic alteration of the tree’s identity.

The thought took root in my mind that the most compelling trees are those that have lived through the most adversity. Big-time adversity is most often provided by dramatic environmental conditions like extreme weather.

In the bonsai hoop house, one of the most consequential environmental conditions is me. I’m constantly doing things to the plants, often involving removing parts of them through pruning or rearranging the directionality of their branching with wire. I do things to them and they recover and go about the work of producing new parts or growing in new directions.

That day I intentionally broke the top out of the little Chinese elm I was engaging in a sort of symbolic act. It was the breaking that made it so. I could have gotten a pair of pruners and cut the trunk in the same location and I don’t think it would have made any difference to the tree. Loss is loss and let’s not even get into any question of pain and suffering (not yet, anyway). I broke the branch in recognition of the fact that I was forever altering the the life story of the tree. I wasn’t playing god so much as I was embracing my role as an environmental factor, like a hurricane or a lightning strike.

Whatever you might make of that, the little tree carried on with no great change in behavior, even though its appearance was drastically altered. It expressed itself through those parts that remained and set about growing new parts.

The first available image of this Chinese elm was made approximately eight years after it was handled in such a rude and forceful way:

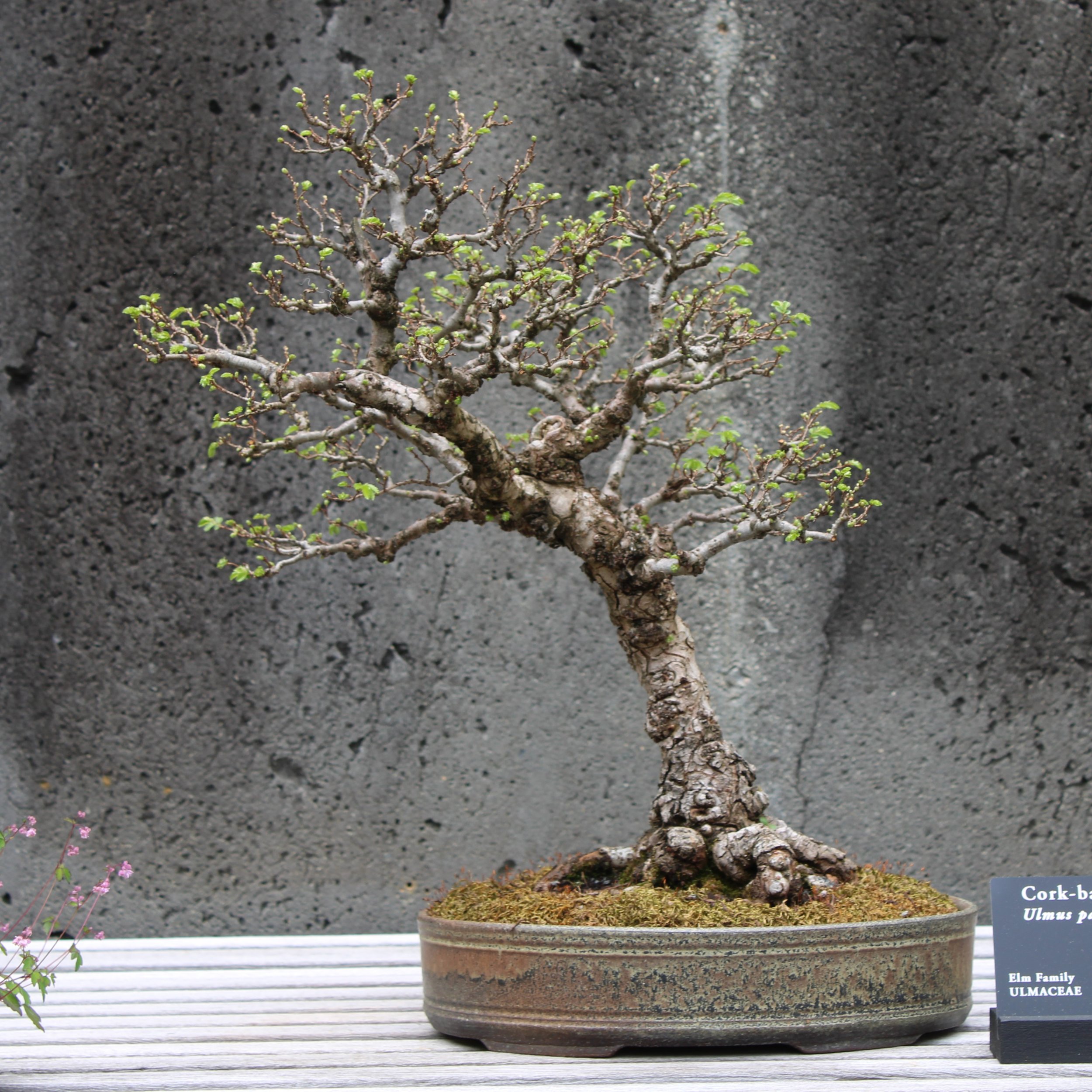

March 2010

The elm did what was expected after the catastrophic event and produced many new shoots. Some of those were selected and allowed to develop into branching, the rest were removed. The staub left by the breaking of the trunk died back until it reached the place where the tree had established its chemical line of defense, and there the die-back ended. Because the staub was of small diameter and comprised of tender young wood, it did not last long and eventually decomposed out of existence. A line of callous can be seen forming in the above image, around the periphery of the wound where dead tissue ends and the living begins. The tree decided where to cut its losses and I went along with its decision.

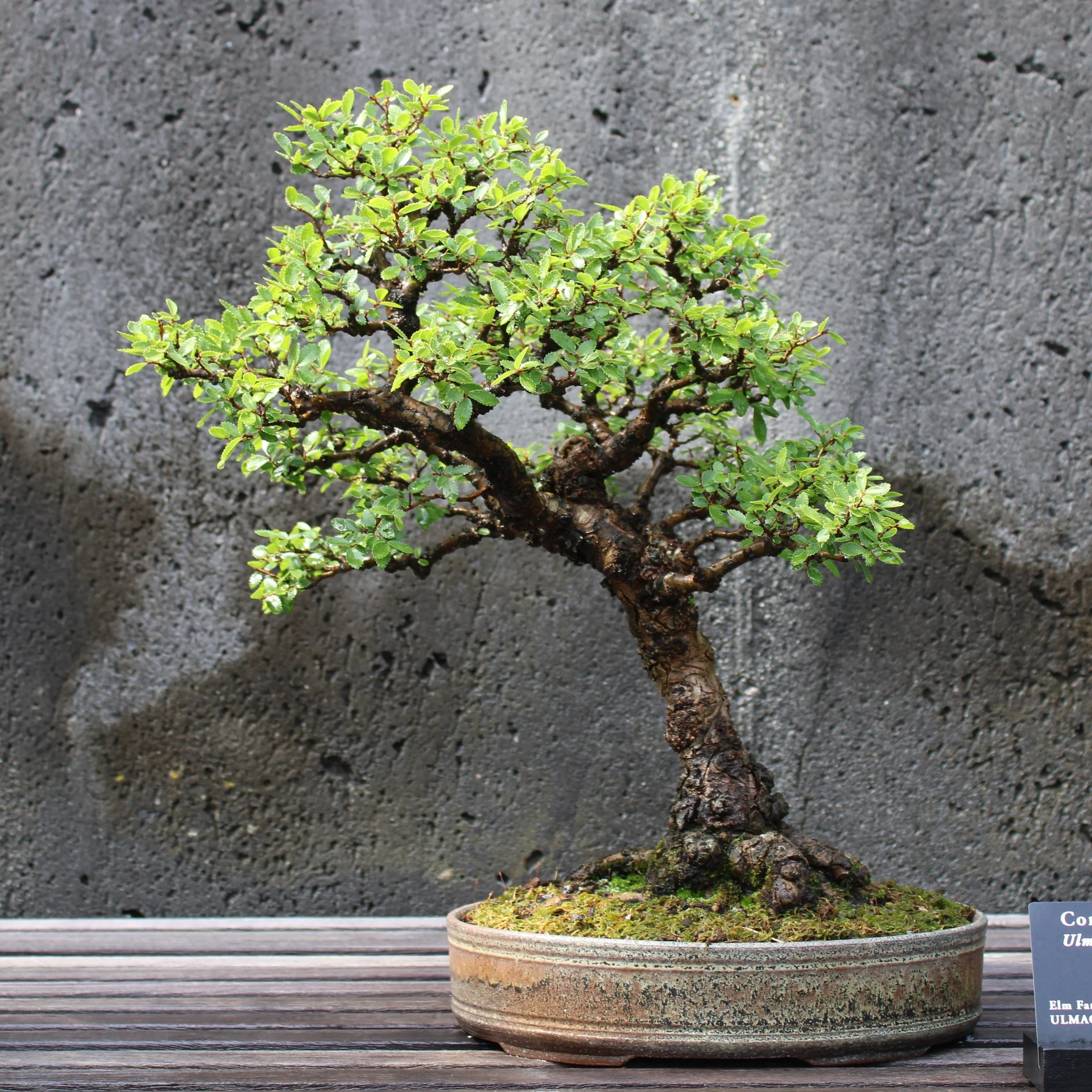

The next available photos come from three years later:

2013

2013

It can be seen in the photos above that the plucky little tree had hardly been discouraged by its misfortune. Instead, the elm continued to push out a multitude of new branching, allowing for further development of a designed structure. Exactly what shape the bonsai might eventually assume was unknown at this point, although the plant was being led in a certain direction. Note that the bark of the elm was beginning to acquire the “corky” look that gives this cultivar its name.

Three more years brought the tree to this stage of development:

2016

2016

A refinement of the design idea, a sort of structural tightening, can be observed by examining and comparing the two above images with the two immediately preceding. This illustrates the incremental nature of the naturalistic approach to bonsai design, which consists of an ongoing dialogue between plant and grower. A different plant would yield a different result. So, too, would a different grower.

Note that the elm has been planted in a new, higher-quality container. The pot, with its subtly articulated glazing, is the work of Mississippi potter Byron Myrick.

The next image shows the cork-bark Chinese elm making its garden debut later that same year. Seeing the picture now makes me think I was perhaps a little premature in displaying this specimen — it looks underdeveloped. It might have been that I needed a small tree to sit on the little display table and nothing else we had looked better!

April 2016

Two years later a series of four images were made of this specimen, offering the first in-the-round photographic documentation:

March 2018

March 2018

March 2018

March 2018

This little tree might be better served by a round pot because that would facilitate showing it from multiple angles. In looking at the above images, I think the elm presents well from several perspectives, and a round pot allows the presenter of such a tree more flexibility in displaying it. Despite that, this tree will probably stay married to the container it’s in, just because I like the pot so well and the combination is pleasing.

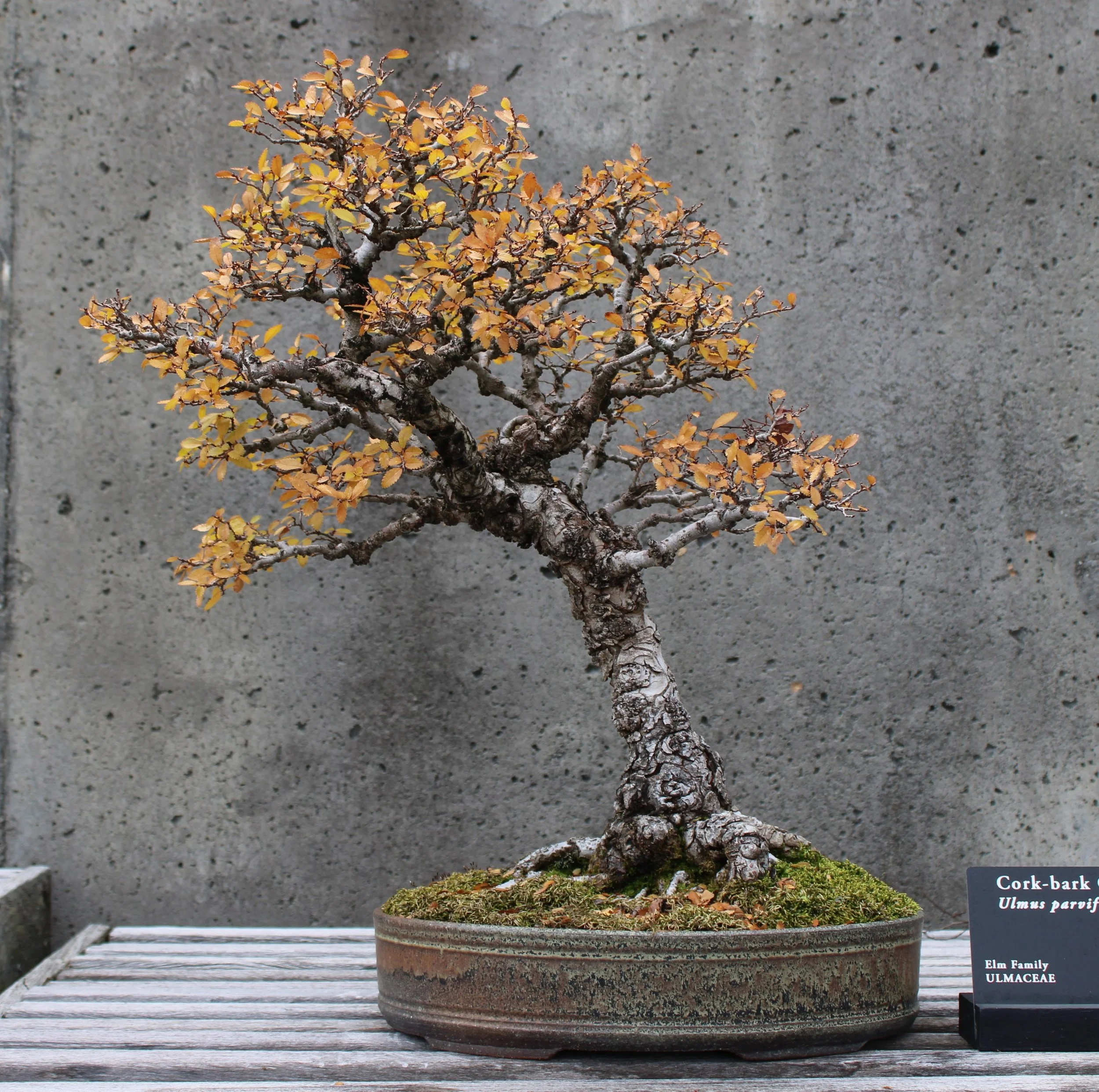

I mentioned earlier that this cork-bark Chinese elm is often on display in the garden, which means it frequently has its picture made. What follows is a selection of images from the last six years, showing the specimen in various seasons and recording the slight but never ending adjustments and modifications made along the way:

October 2020

November 2020

April 2021

April 2021

March 2022

March 2022

November 2022

May 2023

September 2023

November 2023

November 2023

May 2024

October 2024

March 2025

June 2025

December 2025

My friend Ken says that if you can keep a tree alive in a little pot for twenty years, it will look like something. I take that as a comment about the beneficial effects of age on bonsai. People may think of those collected trees that are already hundreds of years old, but even a young tree given a few decades will improve in appearance and presence. The trick, of course, is in keeping them alive and healthy while growing them under the rigors of being in a small pot and getting regularly pruned.

For example, compare the trunk of the elm as it was in its early years with how it is in the most recent photos. There was no reason to think the lower trunk and the base of the tree would end up looking so good! The improvement has much to do with the corky bark, but that feature itself is dependent on the passage of time.

2013

2025

As a side note, in the title of this entry I refer to this tree as “a craggy little elm”, and there’s a reason for that. I think of the tree’s craggy nature as being reflective of tree forms as I know them from a favorite spot off the Blue Ridge Parkway, near Asheville. That place is called Craggy Gardens. The trees of Craggy Gardens and their influence on my bonsai philosophy will be the subject of another entry.