Lightning in a Bottle

Author’s note: Curator’s Journal began in late March of 2022. For reasons not worth the trouble of spelling out, initially the Journal was produced as an asynchronous online educational program. People had to pay a course fee before they could access the site. I thought the fee was pricey, but that was the price I had to pay to get the Journal published at all. The second year of the Journal still had a subscription fee but the cost was less, and the general public had access to a few selected entries. The third year the Journal was set free, made open and accessible to all without charge, which was how it always was intended to be. The fourth year… well, there wasn’t supposed to be a fourth year and now it’s actually close to completion.

To you people who read these words, I say thank you. There is no reason to write except to be read. The total number of Journal readers is not so great (for all its being free), yet the audience continues to grow and I am grateful for the support. I’m also amazed by the scope of readership, as the Journal is regularly looked at by people from almost all fifty states, as well as in scores of countries throughout the world.

“Lightning in a Bottle” was originally written for a chapbook produced at the end of the first year of Curator’s Journal. The chapbook idea came from Rebecca Caldwell, who was the Arboretum’s Adult Education Coordinator at the time and played a critical role in the Journal ever seeing the light of day. At the conclusion of the first year, the little book was sent as a sincere expression of thanks from Rebecca and I to all the people who had signed up for the original course.

The text of the chapbook is now published here as a convenient means of taking stock. When I wrote “Lightning in a Bottle” I was offering a statement of purpose, looking back on the first year and anticipating what was to come. The purpose remains the same. Now, however, there is more road behind than ahead. There’s still good stuff to come, I think. We’ll see how long it takes to produce it.

The past is elusive, that's why we try to keep track of it. Our memory of the past is mutable, that's why we try to nail it down.

I was not so young when I started working at the North Carolina Arboretum, although I was half the age I am at the time of this writing. To speak plainly, I came to the Arboretum searching for a path forward toward a life of purpose and meaning. To speak more plainly, I had already spent all the years of my adulthood up to that point looking for the same path and now I was three years into my thirties and starting to despair of ever finding it. My wife and I had an infant child and a mortgage payment due every month and I was feeling strongly the need to move on from the job I had.

At that time the Arboretum hadn't even been around long enough to be called brand new. It had existed on paper for about three years but few people had heard of it, and the property could not be distinguished from the rest of the National Forest that surrounded it. There was no sign announcing an arboretum, no gardens to speak of, and the few employees already onboard operated out of a trailer parked at the nearby Bent Creek Experimental Forest Southern Research Station off of Highway 191. The Education Center was being built, but that was just a construction site in the woods where no one could see it. The imminent completion of that project in 1990 afforded the Arboretum enough of an increase in State funding to hire more than twenty new employees, roughly quadrupling the size of the existing staff. It happened that I knew one of the few people employed by the Arboretum at the time and he was the one who told me about the hiring opportunity. The job I applied for was termed General Utility Worker, an entry level, bottom-rung position, but it involved working outside with plants. I put in an application, and because the net was spread wide I was taken up in it.

If I were to apply for a horticulture position at the Arboretum today, supposing I was the same age and had the same resume as back then, I doubt I would get even so far as to be called in for an interview. My hiring at the Arboretum was entirely the product of timing and circumstance, a bit of lightning captured in a bottle.

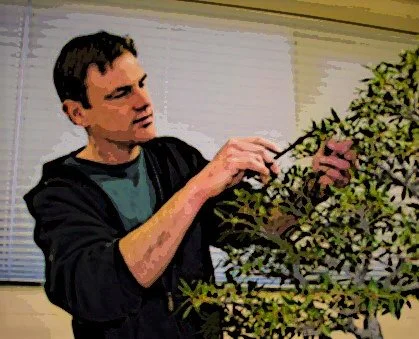

I had been at the Arboretum for less than three years when a rumor started circulating that we were considering the possibility of taking on a donation of bonsai trees. I knew so little about bonsai then that I might as well have known nothing. It was a genuine surprise to me when it was proposed that I might be given responsibility for the stunted little trees when they arrived, and I tried to turn down the offer. The offer came right from the top, though, and was wrapped in the words possible career opportunity. I was not in a position to say no, so I said okay, as long as it didn't interfere with the work I was already doing. Assured that it would not, that I could keep doing what I was doing and then do the bonsai in my spare time, I went my way perplexed at the turn of events but satisfied that it was no big deal and would probably blow over in short order. Here again I was the unwitting beneficiary of timing and circumstance. Once more lightning had found its way into a bottle that was then handed off to me.

The Arboretum's bonsai enterprise looked for all the world like a hopeless misadventure when it began. The plants received in the initial donation were unkempt and in poor health. They were entrusted to someone who knew nothing about bonsai and who was not particularly enthusiastic about learning bonsai because he was still trying to get a handle on basic horticultural skills. They came without any funding support, and the Arboretum at the time lacked any of the supplies and materials needed for bonsai work, or any strategic plan for development and utilization of a bonsai collection. The unhappy little plants came to a startup public garden in a part of the country that at the time might have been charitably described as a bonsai backwater. On top of all that, bonsai had come to an institution focused on promoting Southern Appalachian flora and culture, and if there was a way to make little Japanese trees fit in with that program it was not immediately obvious to anyone.

Enter Dr. John Creech, with his impeccable horticulture credentials and his good nature and buoyantly positive outlook. Enter Dr. Creech, and with him Bob Drechsler and Janet Lanman and all the other good folks at the National Bonsai and Penjing Museum in Washington, DC, who helped me get on my feet and headed in the right direction. Connections made at the Museum led me to Yuji Yoshimura and the life-changing experience of learning from him. Then, again through Dr. Creech, came the experience of traveling to Japan to study with Susumu Nakamura, affording me a wider perspective on the bonsai world. And let me not forget the others - E. Felton Jones, Dottie Wells, Dr. Bev Armstrong, Dr. Bob Murray, Dana Markham, Virginia Turner, and so many more. Too many to name here, but every one of them important helpers. If you were to gather together all the people I had the good fortune to meet along the way, all the helpers who cared enough to do what they could to make bonsai at the North Carolina Arboretum succeed, they would overflow whatever stage you put them on. And they would blind you with their benevolent light, because each one of them would be shining like lightning in a bottle.

The paragraphs you just read are the product of me writing history. That might sound pretentious, but only if you have illusions about how history comes to be recorded. Our collective consciousness of the past is full of gaps, contradictions and inaccuracies. History is ultimately shaped by those who write about the things that happen, and then by whomever reads that writing and what, if anything, gets made of it. In writing this composition, as in writing many of the entries in the Curator's Journal, I am giving my remembered first-hand account of events in which I was an active participant. That makes me an eyewitness, although hardly an objective or unbiased one. But it is precisely because this particular story is so personal to me that for the past few years I have felt a growing desire, and even a need, to write it down. If I don't write the story, who will? If someone else were to write the history of bonsai at the North Carolina Arboretum, with what information would they be constructing their narrative? What perspective would that story have? If the story doesn't get written at all, after a while it will be as if the history never happened. All the extraordinary coincidence and good fortune that marked the adventure and all the good people who nurtured it along the way will be forgotten.

I think of history as the tale we humans tell ourselves about who we are and how we got here. Recording the history of bonsai at the North Carolina Arboretum is one significant part of what the Curator's Journal is about.

This leads directly to an unavoidable question: Is the history of bonsai at the North Carolina Arboretum worth recording?

I think it is. What happened with bonsai at the Arboretum is as remarkable as it was unlikely. When you understand how humble our beginnings were and consider how many obstacles had to be overcome just to stay in the game, and then take stock of where we are today, the Arboretum's bonsai program presents a compelling story of success against the odds. Those kinds of stories are always worth telling. But the nature of the Arboretum's bonsai success imbues our story with greater importance. We started out in circumstances that could easily have been construed as too limited or too disadvantaged, and instead those same circumstances became the impetus to act creatively. The North Carolina Arboretum has been surprisingly successful with bonsai precisely because we approached it differently — thought about it, practiced it and presented it differently — and people responded favorably to the difference. We took a creative risk and made it work.

How did we come to do bonsai differently, and what exactly is the difference? Why did we feel the need to take any risk at all? The answers to questions like these might be useful, because by studying strategies that lead to success, the results might be replicated and improved upon. That is another part of what the Curator's Journal is about. It records the history of bonsai at the Arboretum, explaining how it came to be the way it is, but the Journal also interprets the meaning of what happened and offers an explanation of why it should matter. Interpretation is a critical element of what any recorder of history does, even when solemnly cloaked in a mantle of authoritative objectivity. How we think about what has happened influences what happens next.

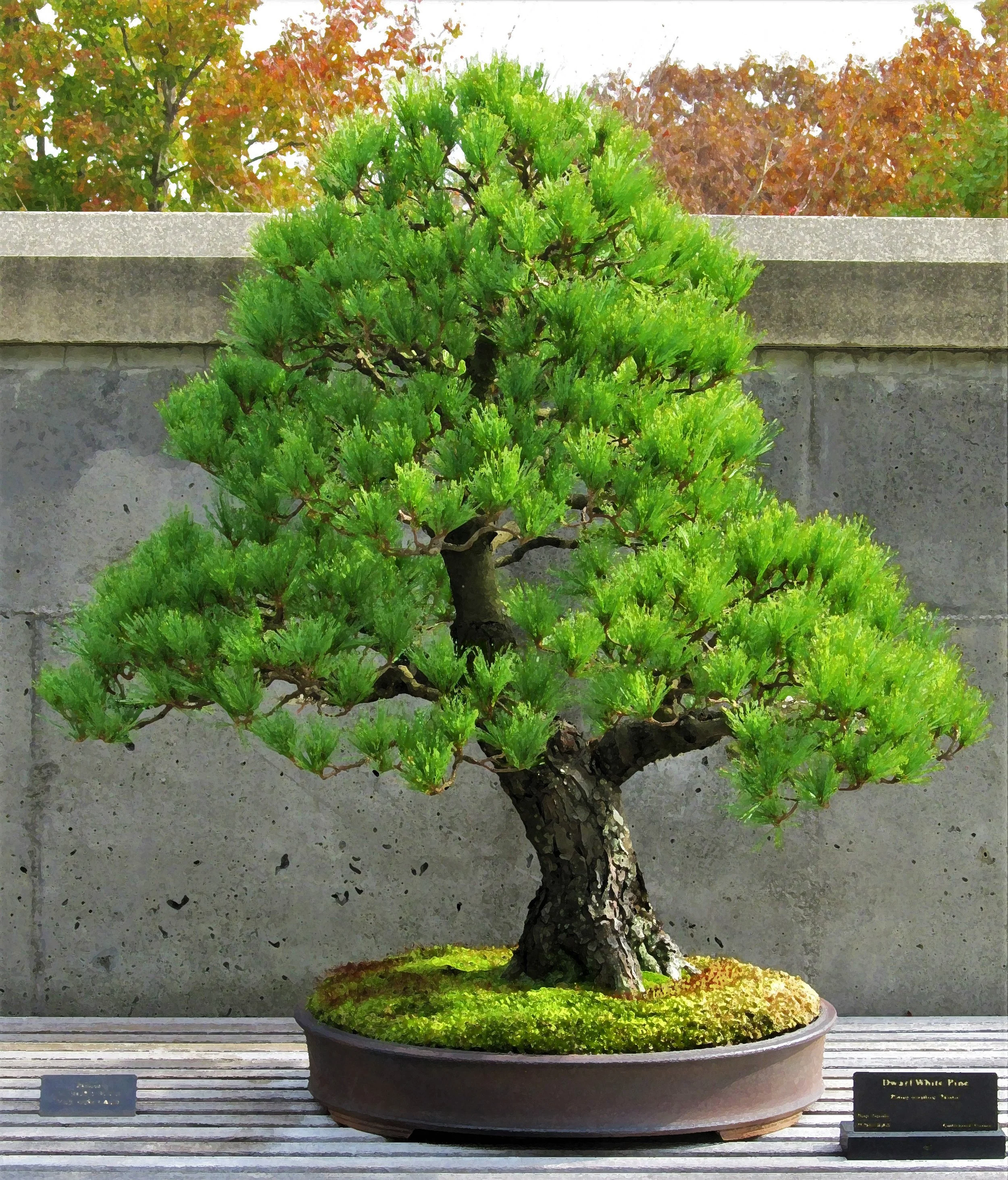

Writing and interpreting the history of bonsai at the Arboretum is a weighty undertaking, but the Journal is about more than that. There are more than one hundred fifty specimens in the Arboretum's bonsai collection. They all have a history unto themselves, and some of the stories of the trees are exceptional. Even the more modest tree stories are appealing, and should be shared if for no other reason than to satisfy curiosity. All the information we know about the individual specimens in our collection is worth preserving before it is forgotten. There is also horticultural information attached to all the different plant species, first-hand knowledge learned through experience, over decades of doing. Although not intended as a course in How to Grow Bonsai, the Curator's Journal inevitably delivers lessons along those lines, simply in the process of telling tree stories and recording styling and seasonal maintenance activities.

Beyond the bonsai collection, the Journal also is a vehicle for recording similar information about the Arboretum's bonsai garden. The garden might be seen as a separate subject in its own right, but probably not by people who read the Curator's Journal. Journal readers know that the bonsai garden and the bonsai collection it showcases are two sides of the same coin; the garden exists to enhance the experience of viewing the bonsai and the bonsai never look so good as they do when they are seen in the garden. The garden is, in fact, the full realization of the North Carolina Arboretum bonsai expression. It is at the heart of our bonsai history and as such it deserves to be central to the Curator's Journal.

That’s a lot of ground to cover. As of now the Journal has been publishing for a year. While I wouldn't say we are only getting started, I wouldn't say we are getting close to the end, either. There remains much to write about. If there are still people interested in reading, I am still good for telling the story, in as many smaller stories as it takes to do it. Writing history and doing right by what happened is a tricky business, sort of like catching lightning in a bottle. But I have some experience with that, so I feel optimistic about the prospect.