Wabi-Sabi, Maybe?

Wabi-sabi is a phrase that sometimes turns up in bonsai discussion. It's a combination of two Japanese concepts: wabi, generally construed as meaning understated, simple, beautiful; and sabi, meaning aged, worn, humble. This is my own understanding of the two terms, as it seems the definitions are not agreed upon universally. In fact, all evidence suggests that the exact meaning of the phrase wabi-sabi itself is subject to myriad readings. There does seem to be, however, some broad agreement that impermanence and imperfection are central to the wabi-sabi concept, regardless of what the words might mean individually. Here the phrase connects with Buddhism and the three marks of existence (impermanence, suffering and emptiness). This is all very interesting and the subject runs deep, as I've learned from conversations with my friend Felix Laughlin. He has been an earnest student of wabi-sabi for some time and has gone about educating himself on the subject with the intellectual rigor you'd expect from a career lawyer. If you ever want to have an intensive discussion about the subject of wabi-sabi and its history, to plumb the depths of the phrase’s ambiguity, perhaps to contemplate the full ramifications of its meaning as a philosophical perspective, Felix would be an excellent person to talk with. On the other hand, I would not be.

Sorry to say, wabi-sabi and I got off on the wrong foot. I hadn't known anything about the idea of wabi-sabi before engaging with the world of bonsai, and then the phrase kept popping up. When I'd ask people what they meant by wabi-sabi their definitions were vague or squishy, and then one day somebody told me that it was a Japanese thing and most Westerners could never understand it. That sealed it for me. I put wabi-sabi aside in a big box where I kept all that sort of stuff and decided I shouldn't waste time worrying about something I probably could never understand anyway. It wasn't until years later when discussing the subject with Felix that I realized wabi-sabi might be something I could understand. When I learned that the phrase related to feelings of melancholy, longing and an aching sense of the relentless passage of time, prompted by the experience of certain phenomena, it struck a chord of familiarity. I was no stranger to that sensation. Usually it arose upon the sight of a certain thing or being in a certain place, although the sensation might also be associated with a sound, or a smell, or an atmospheric condition, or a time of year, or a time of day, or some combination of any or all of those things. The sensation is a swelling of feeling, the way that joy is a swelling of feeling prompted by something that makes you happy, or rage is a swelling of feeling arising out of something that makes you angry. The sensation I know, the one I think might be wabi-sabi, is powerful — intense like joy and anger, but is more difficult to describe. To say the feeling is sadness doesn’t begin to capture the entirety of it, although sadness is definitely an element within it. Words fall embarrassingly short of expressing the intensity and fullness of the experience.

My conjecture is that what I sometimes experience might be wabi-sabi, but in fact I could be way off base arriving at this conclusion. I want to talk a little more about this powerful sensation though, whatever it might be, because that certain feeling ties in directly with my bonsai thinking. Actually, putting the two in their proper relationship, bonsai has become the vehicle by which I creatively interpret and reflect the feeling, which was there long before I knew anything about bonsai. To simplify the matter, I will go ahead and use the term wabi-sabi in this entry as the best available handle to give the thing. If there be any reader who takes their wabi-sabi very seriously and feels I am missing the mark in making this connection, please forgive me. I’m just another hopeless Westerner.

To avoid depending too much on words to express all that's encompassed by this deep sensation, allow me to share with you some photographs I've made over many years, seeking to visually capture the sensation by recording certain sights that have prompted it.

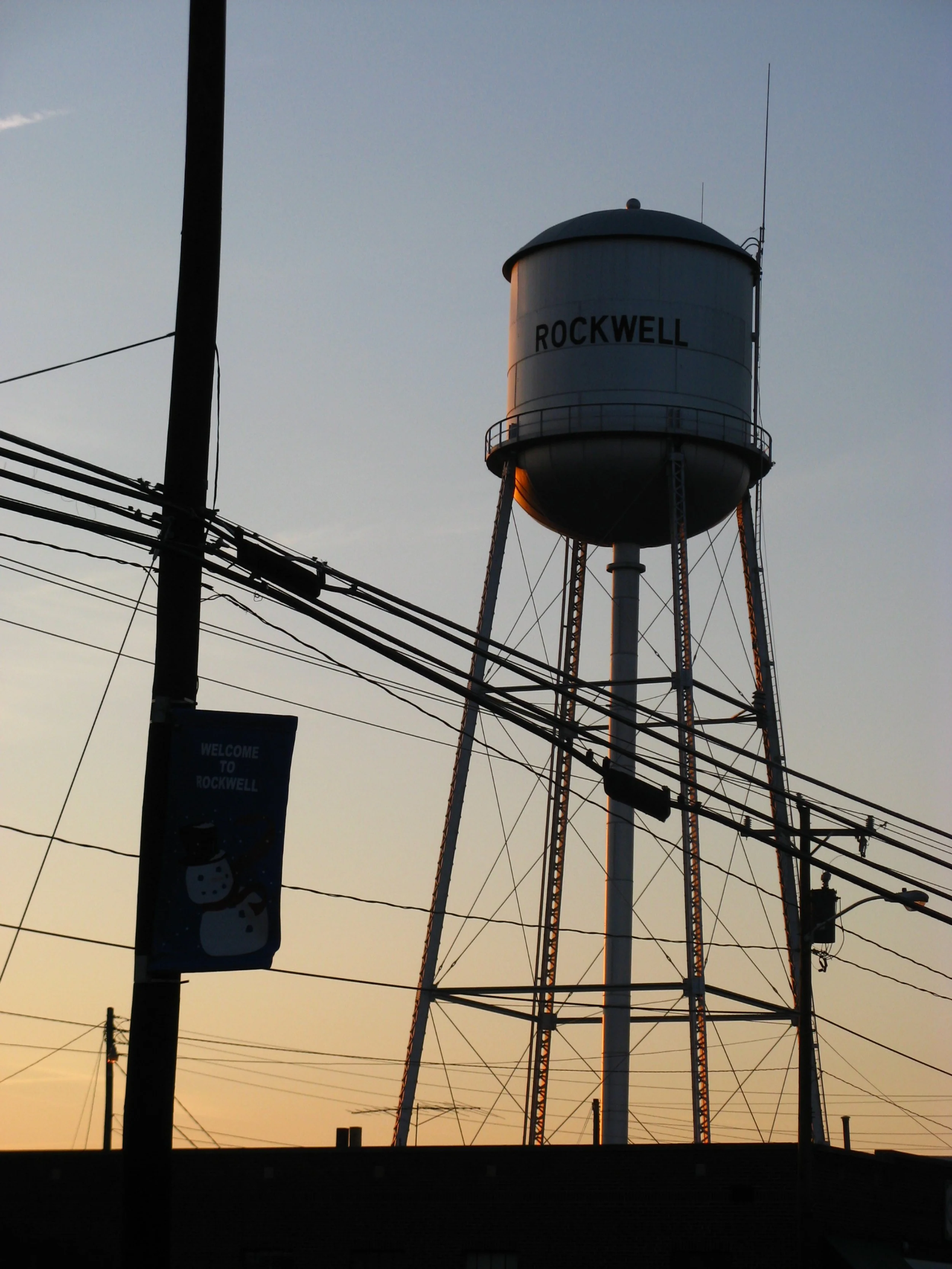

I had the wabi-sabi feeling strongly when I visited this place:

My response should be no surprise, as the rock garden at the Ryoanji Zen temple in Japan was created specifically to express and promote wabi-sabi. But I also had the feeling when I made this picture while visiting an historic site in New Jersey:

The twilight time of day certainly contributed to the sensation because twilight is both beautiful and brief, only minutes in duration. The ethereal lighting is wonderful, but it is more the fugitive nature of the effect that makes it wabi-sabi. The old buildings at that place in New Jersey also contributed to the feeling. Old buildings in an of themselves are often wabi-sabi because they speak of the passage of time and the inevitable decline and decay that accompanies aging. Wabi-sabi is all about that.

There can be rustic warmth in wabi-sabi, a sense of earthiness that is rough and weathered:

The wear and tear visible on various objects due to the passage of time is a reminder of the effect that phenomenon has on all things. Wabi-sabi is the patina of corruption that comes to all aging things.

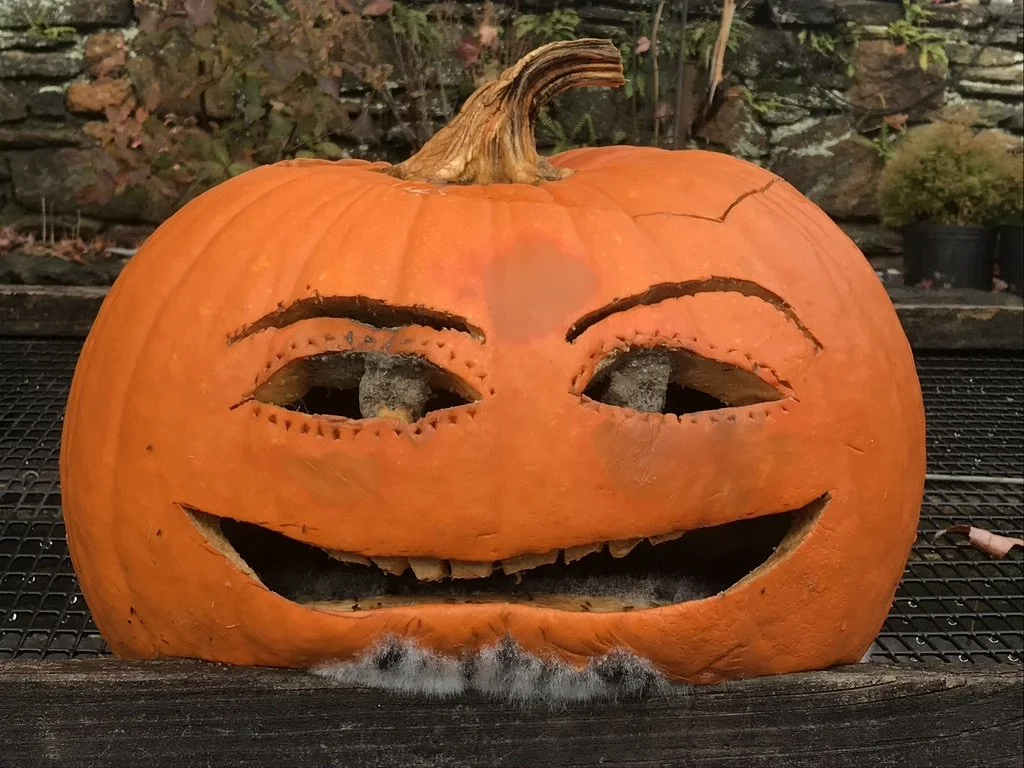

Sometimes those wabi-sabi objects look back at you with unblinking eyes that stare across the ages:

There are times and places where the sense of wabi-sabi is so heavy it feels as if it might pull you in and hold you right there forever. It’s in the sights and sounds and smells. It’s in the atmosphere all around you, and you breathe it in.

No human element other than the observer need be present. The capacity for wabi-sabi seems to be inherent in nature, given the right circumstances.

In western North Carolina we are surrounded by an ever-present source of wabi-sabi. The Southern Appalachian Mountains are among the oldest mountains on earth, having formed some four hundred eighty million years ago. As we see them today, they are in a process of long, slow decline, weathering, shrinking down to eventual nothingness.

And, oh yes, wabi-sabi is in trees. It is particularly manifest in old trees, trees that have lived a hard life, trees that are in slow decline, trees that are already partly dead and even in the remains of those that have died.

This aspect of trees as physical manifestations of the effect of life in the field of time is the real reason wabi-sabi is integral to the concept of bonsai. On the surface it may seem to be all about culture. Below the exotic facade, however, is an element that resonates to one degree or another with all human beings in all places on earth because it deals with the central reality of our existence. Wabi-sabi is the state of recognizing that time passes — that time has passed and that time will pass, and here we most temporarily stand in the single moment that exists between. No wonder the sensation is powerful. How could confronting one’s own mortality be anything less?