Finding Form

A previous Journal entry titled Crazy Horse told the origin story of that specimen — an old eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana) — as a collected tree. Those interested to know more about the background of the specimen held up for examination in this entry — another old eastern redcedar — need only refer to what was written about Crazy Horse. In a manner of speaking, the two trees are siblings. It’s unlikely they are truly related, but both redcedars were collected by the same person around the same time from the same general location.

Right from the beginning, the redcedar that came to be called Crazy Horse was thought the better of the two, its claim to superiority based on having a fantastic display of deadwood in its trunk. The other redcedar also had an old trunk with deadwood, yet it lacked the extravagant flair of its counterpart. The trunk of this lesser tree was long, thin and scraggly in appearance. Both specimens had raggedly wild branching and the same coarse redcedar foliage, so the advantage of one over the other was mostly a matter visual appeal in the trunk.

As it happened, the subject of this entry was first to receive attention in its development as a bonsai. In 2001 we had Mr. Qingquan Zhao of China here on a visit and had him work on the tree in a public demonstration. Mr. Zhao is an acclaimed penjing artist known best for his “water-and-land” tray landscapes, although he is also expert in creating single tree bonsai in the Chinese fashion. The Arboretum hosted three visits from Mr. Zhao in the late 1990s and early 2000s that were highly influential in my development as a curator, and by extension influential in forming our bonsai identity.

The following photographs of the redcedar we asked Mr. Zhao to style were made shortly before his demonstration:

March 2001

Regretfully, no photographs exist to show Mr. Zhao at work on the tree. Even worse, there is no visual documentation of what the redcedar looked like when he was through with it, although I remember fairly well how events played out. Most of the redcedar's branching was removed and the tree was put into a bonsai container during the demonstration, so it was subjected to a lot of stress. In response, I let the redcedar grow more or less unmolested for the remainder of 2001 and all of 2002. It is always a good idea to allow a recovery period after an intensive session wherein much is removed from a tree. Letting it grow unrestrained for two entire growing seasons is usually not necessary, however, and in some cases might negate the styling work that was done in the first place. In this particular case it was not a bad thing to do because the tree in question is an older specimen and those take longer to regain vigor. That’s a rationalization, though. The truth is that I did not have the time in those busy days to give this redcedar any attention.

The next available image of this specimen is from 2003, and here we can see that the tree had become overgrown and lost much of the definition Mr. Zhao had given it:

2003

I feel the need to emphasize that the photo above is not a fair representation of Mr. Zhao's work. That talented artist had two hours in which to whip some shape into a wild and unruly plant during a public demonstration. The image is from nearly three years later, the redcedar having received absolutely minimal maintenance in the interim. However, in examining the photo it is possible to gain an approximate idea of how Mr. Zhao approached the material. Although the tree has changed substantially since, even today it is still largely laid out according to the overall design structure the artist gave it back then. He’d have no memory of this tree today, and he might not like the way it looks if he saw it now, but some of Mr. Zhao’s original vision has always remained in this bonsai.

Fast forward four years and we find the redcedar considerably more refined in its development and out on display in the bonsai garden:

November 2007

It will be noted in the above image that guy wires were used to reposition heavier branches. Teaching an old dog new tricks is often easier than training an old tree branch to assume a new position, and the guy wire method allows for holding a branch in place for the several years often needed to accomplish a desired result.

Refinement of the redcedar continued for the next few years as the specimen was regularly featured on display in the garden:

June 2009

September 2010

All in all, the redcedar responded well to the training it was given. The tree did what it was asked to do, but problems arose when the person growing the tree began to have a different idea about how little trees in pots are supposed to look. The eventual result was another overhauling work session, in which the redcedar was sent in a different styling direction. This occurred in early 2014. Here’s what the tree looked like going into the session:

February 2014, before

And here is what happened:

February 2014, after

As documented in the above set of images, in 2014 this specimen underwent a form of horticultural conversion therapy. At that point I discontinued training the redcedar to look the way I thought a bonsai was supposed to look and began thinking of it instead as a little tree, training it accordingly. This represents a sea change in philosophical approach and yields a much different end result.

Here is a follow-up image made at the end of that same growing season, showing the vigor with which the redcedar responded to the new work:

September 2014

Looking at the above photo, I can’t help thinking that it was meant to be a “before” image. That is, the picture was taken before another work session commenced, with the intention of later taking an “after” picture to show what was done. No such post-session picture exists, however. In fact, no other photograph was made of this specimen for the next eleven years, and during all that time the specimen was rarely worked on and never made it back on display in the garden. It’s difficult to account for this neglect. I liked how this tree worked up when it was redesigned in 2014 and I can’t recall anything particularly unfortunate happening in the time since. Perhaps it all traces back to my original conception of this tree being the lesser “sibling” of the two collected redcedars that came to us in the late 1990s.

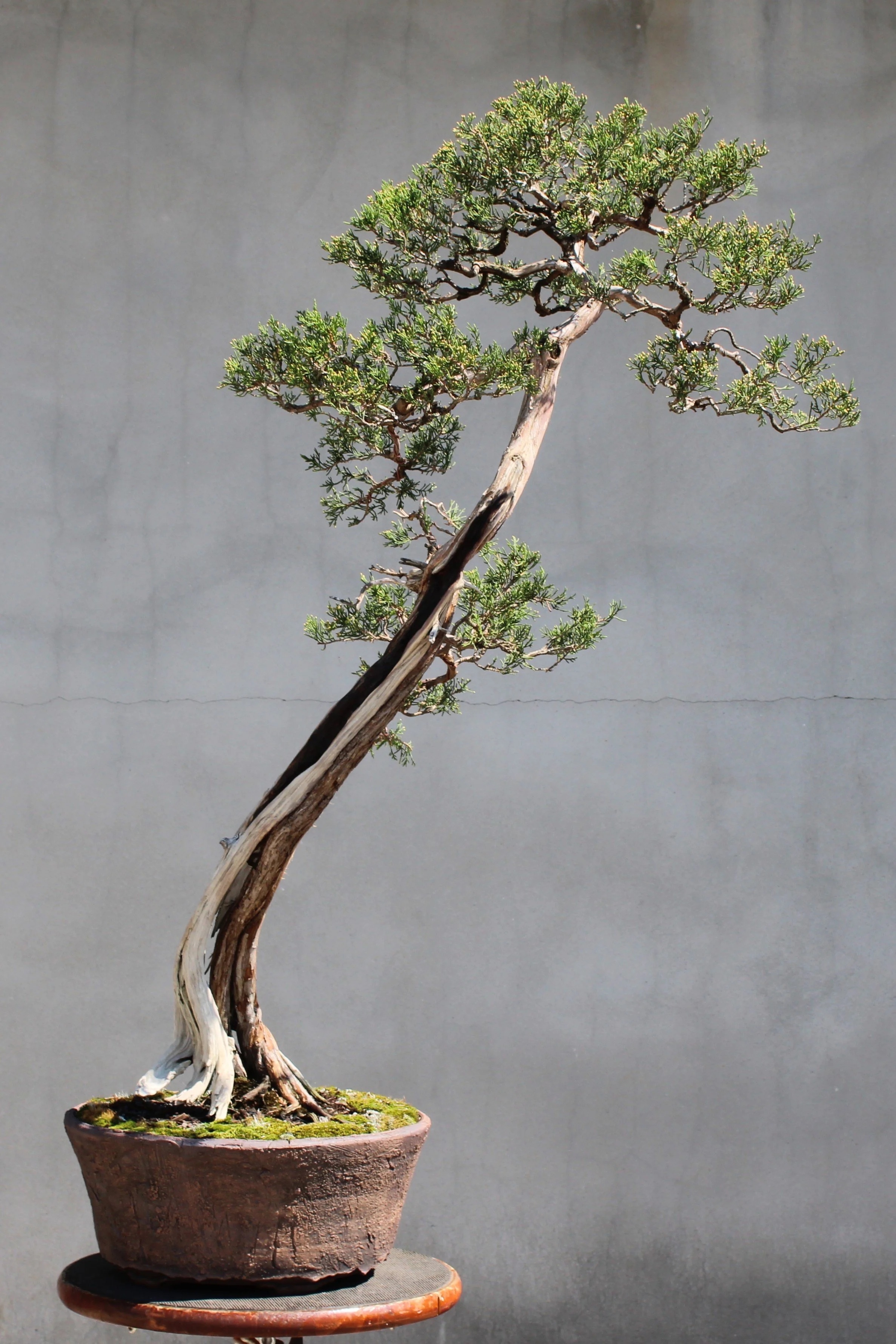

In any event, just last month I took notice of this tree languishing in the hoop house and decided it was time to give the neglected child some attention. Here is the state I found it in:

August 2025

It will be noted that the tree as seen above is growing in an oversized production-grade container and planted at an extremely slanting angle. The big pot was chosen to give the tree a little more room for its roots as the specimen was being allowed to grow with little restraint. The severe lean was instituted to raise the base of the deadwood line of the trunk so it would not be in contact with the ground. My purpose was to slow the rate of rot in the deadwood base. Both these actions were taken a few years back in recognition of the fact that the redcedar was operating on the auto-pilot principle. That is to say, the tree was being left to grow more or less unrestrained, and I potted it the way I did in order to allow for that while minimizing potential negative side effects.

These two photos show the redcedar propped up to approximate the posture it would once again eventually have:

August 2025

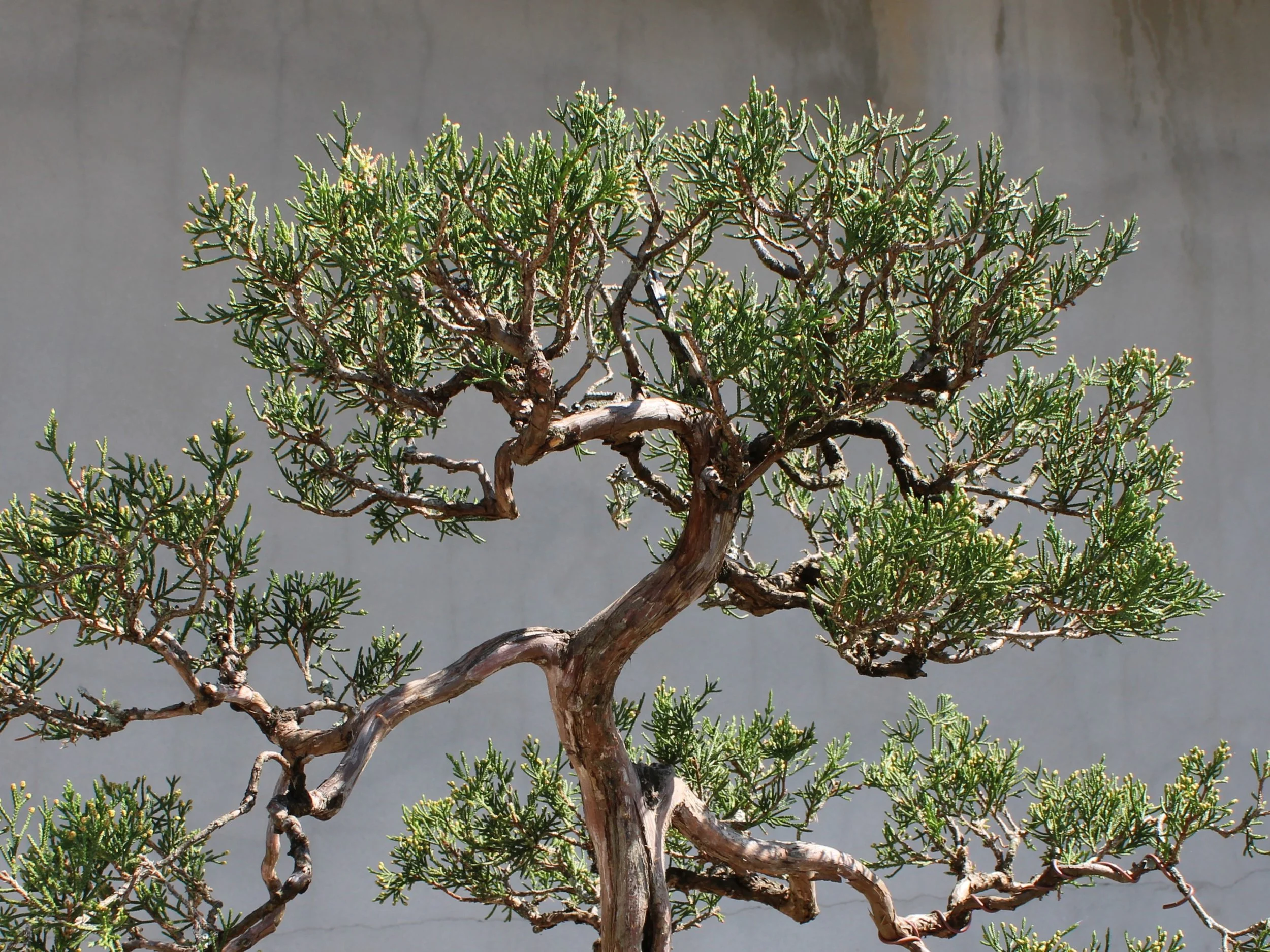

Much was done with this tree over an approximately two-week period. The branching was all pruned thoroughly and the foliage was thinned out and shortened. Minimal wiring was done to make a few adjustments to key branches. The deadwood received a little additional carving, then was cleaned and given a light wash of lime sulfur, with certain interior sections being charred with a torch. Finally, the tree was repotted back to its proper position, planted in a new container made by North Carolina potter Preston Tolbert.

Here is how the specimen looks today:

Here is an alternate idea for presenting this tree, rotated just a few degrees clockwise from the above view:

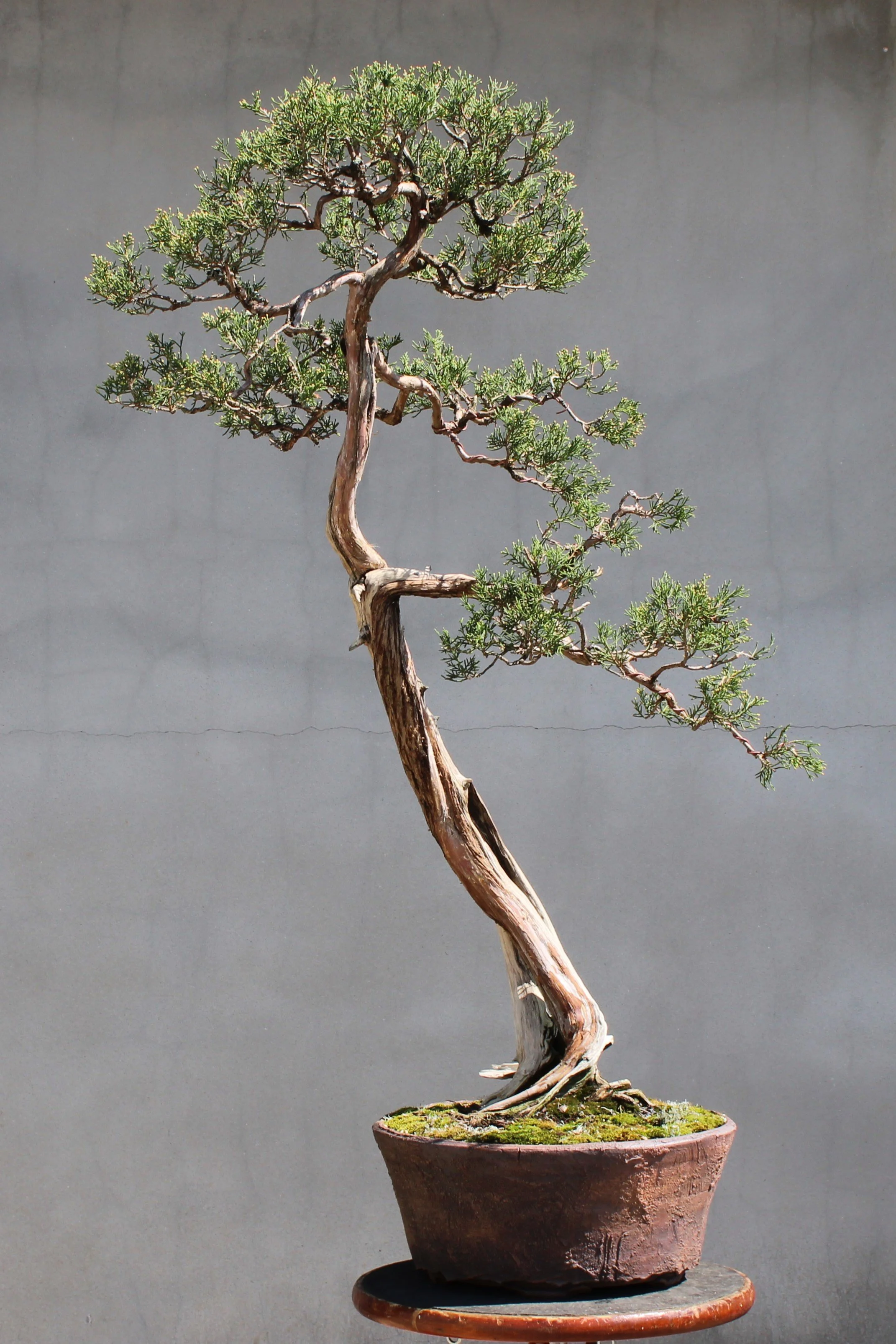

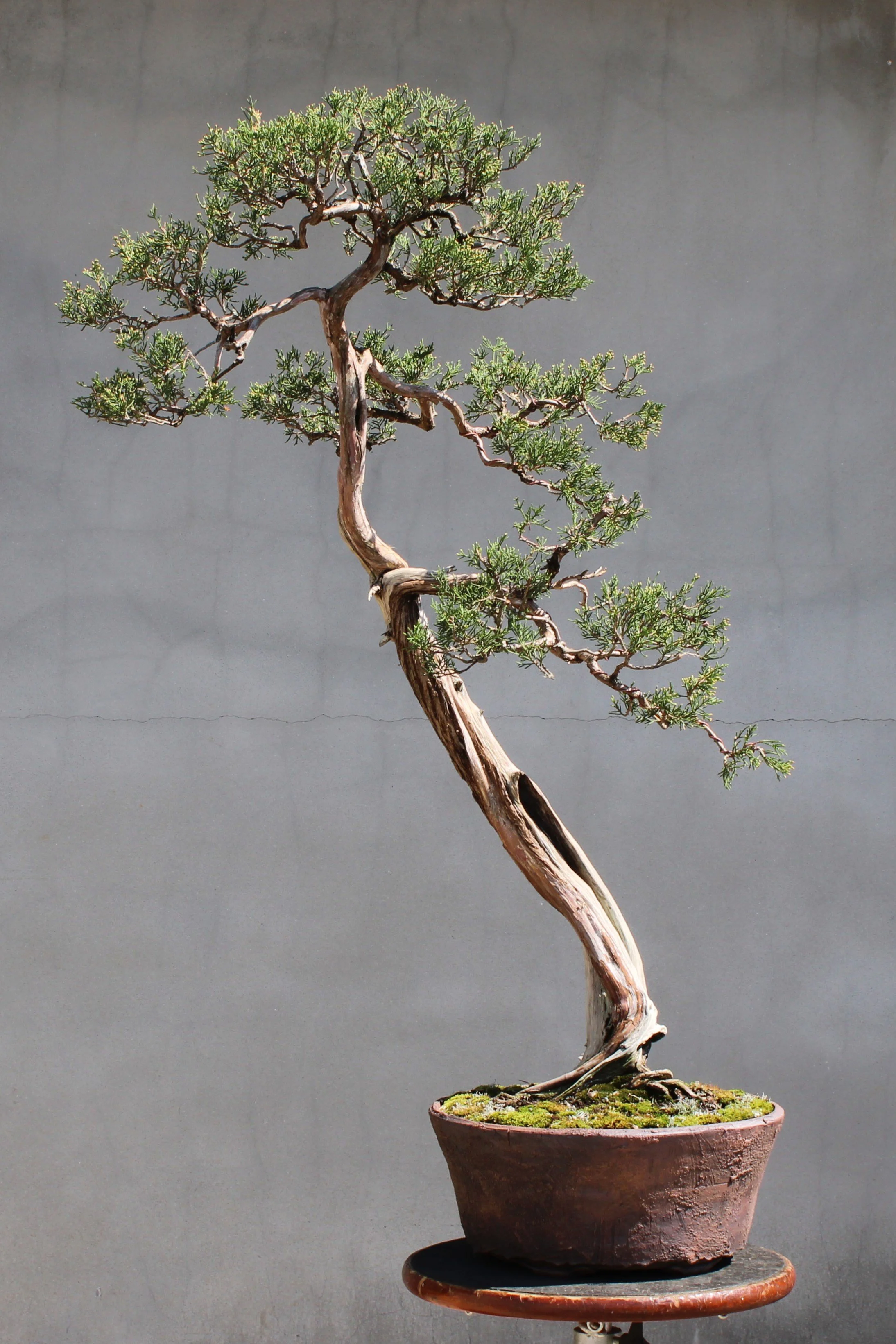

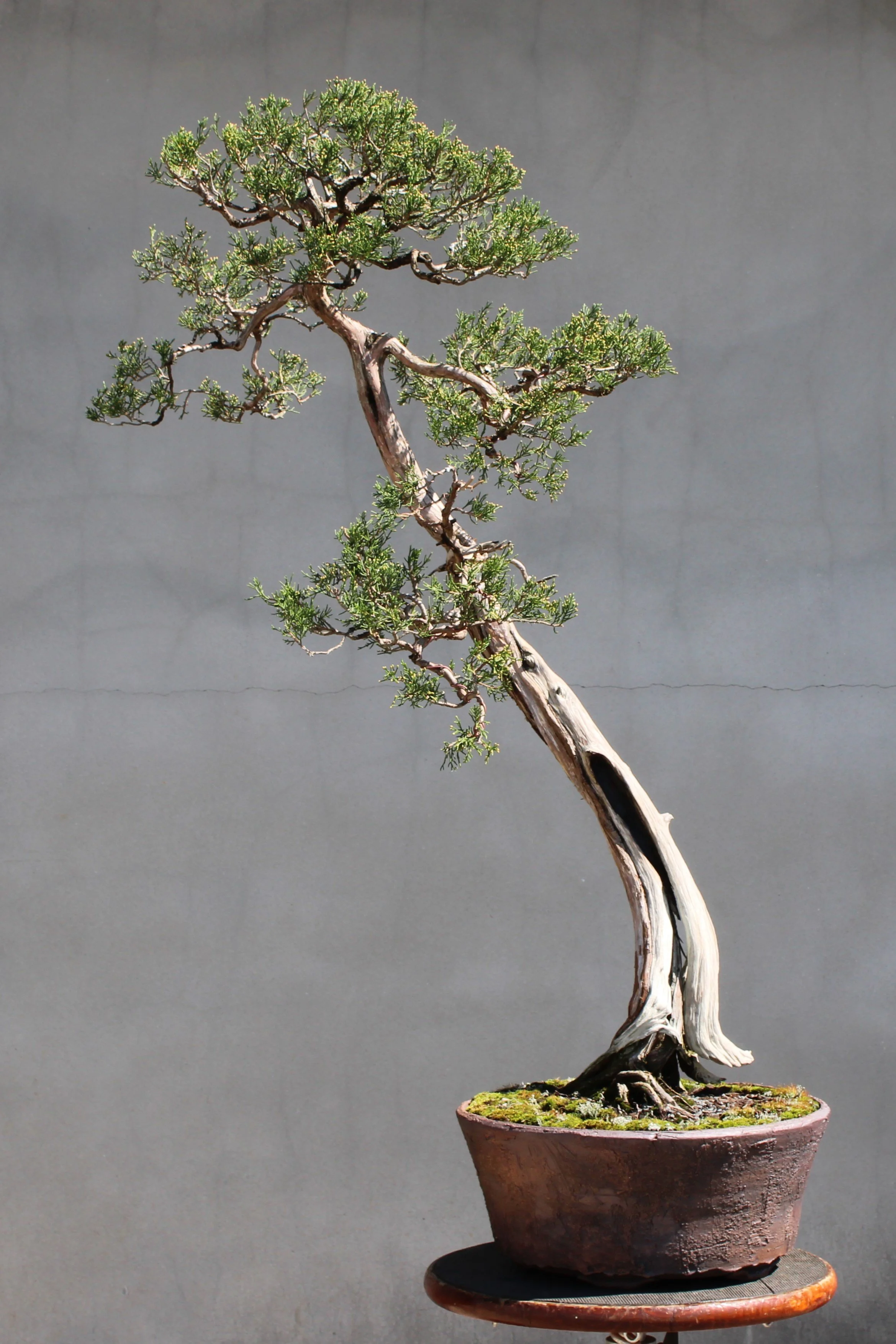

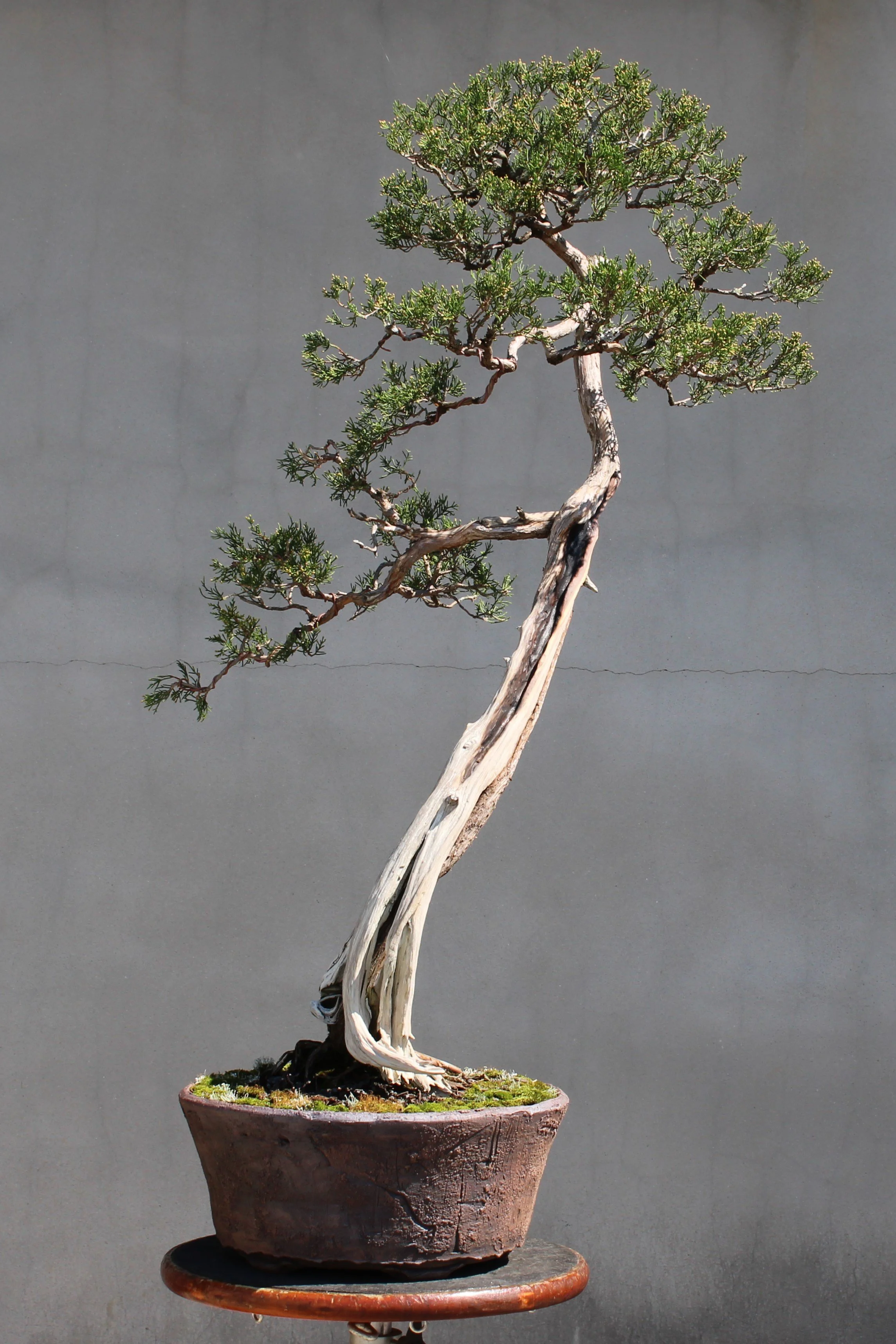

Here are three other perspectives to provide a more in-the-round idea of the redcedar’s current appearance:

Deadwood details:

A comparative view of the base before and after repotting, showing the effect of the tree being repositioned to a more upright posture but still holding the dead part off the ground:

A comparative view of the top of the tree, as it was originally styled and how it looks today:

2014

2025

The long, slow progression of an eastern redcedar bonsai in four easy pictures:

2003

2010

2014

2025