Entertaining the Alternative

When I started out in bonsai there was a clear line of demarcation between the little tree art of Japan and the little tree art of China. The bonsai of Japan were held up as the highest attainable standard. The bonsai of China, properly called penjing, were looked at askance, denigrated and dismissed as crude and altogether inferior. A poorly executed bonsai would be jokingly described as Chinese style. At that time virtually all bonsai instruction came from Japanese teachers, or those who had been taught by them, or from books and magazines reflecting that same perspective. In the first few years after the Arboretum's bonsai enterprise began we amassed a library of about thirty or so bonsai books, almost all of them received as donations. All but two of these books presented the Japanese way of designing little trees. I spent a lot of time studying those bonsai books, and when on occasion I picked up one of the two Chinese volumes we had my sensibilities suffered a sort of whiplash from what I saw.

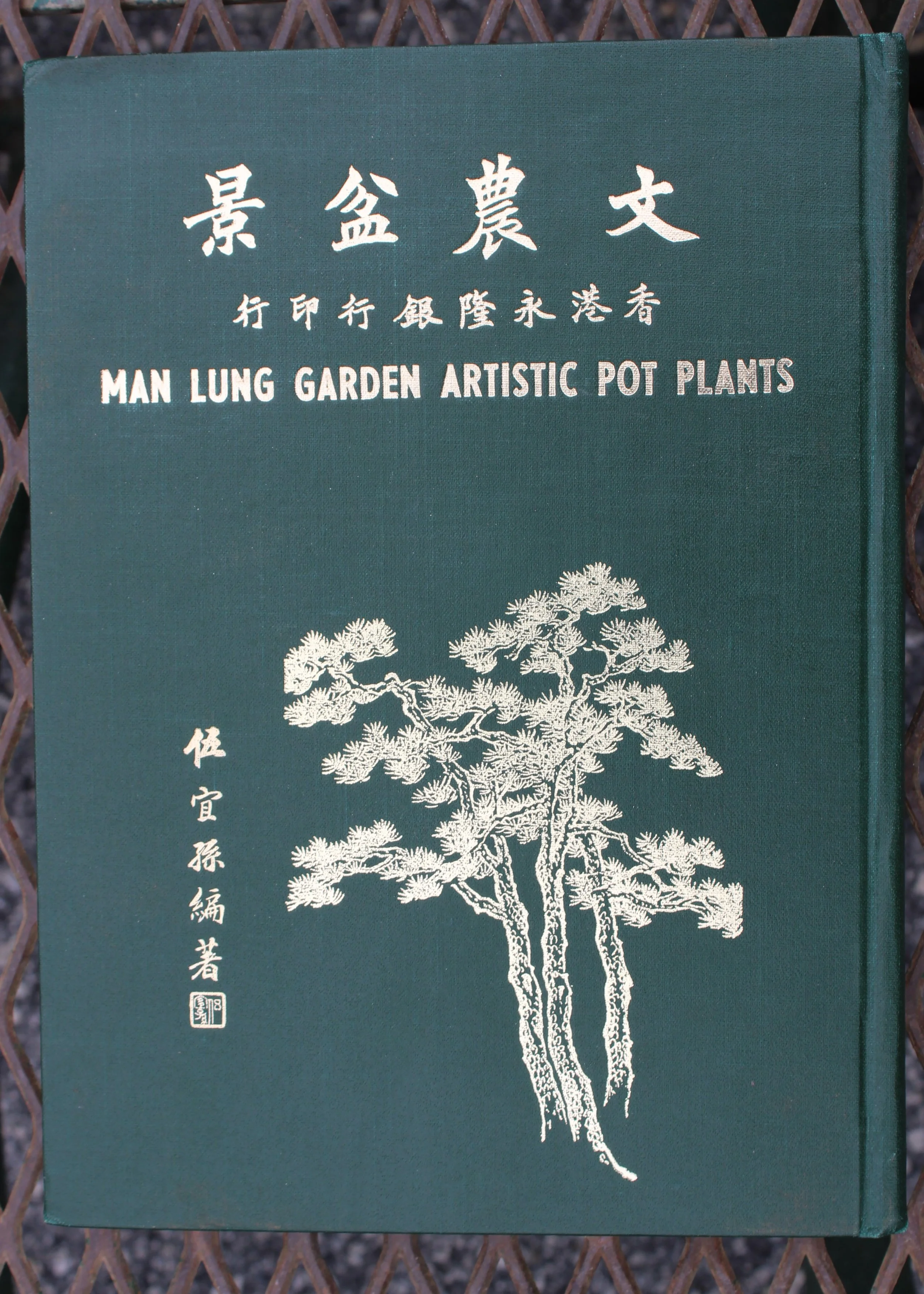

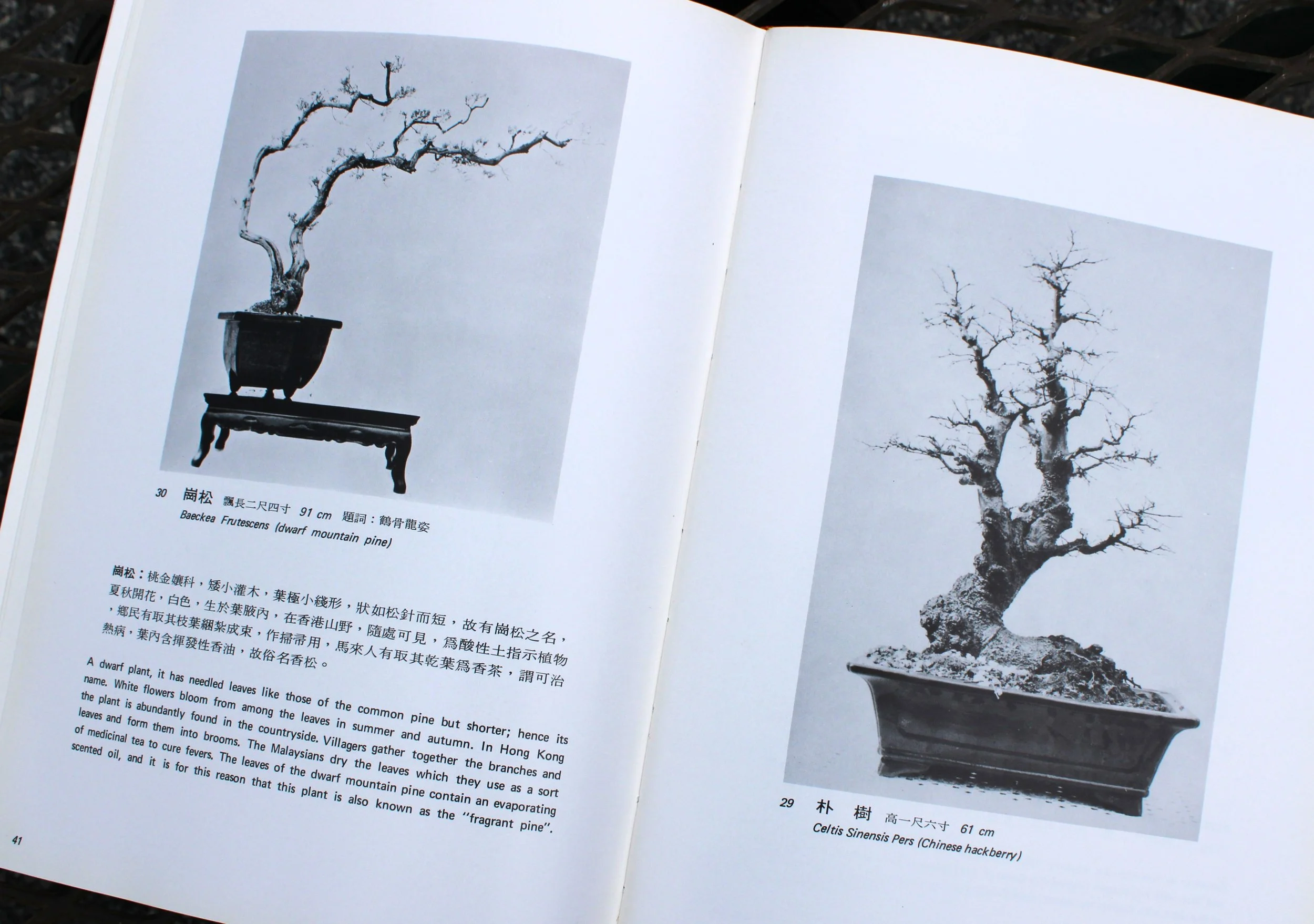

One of those penjing books was titled "Man Lung Garden Artistic Pot Plants". For many westerners, including me, this privately published 1969 volume with its black and white photographs was a first exposure to the Chinese little tree aesthetic. The strange name of the book proved a suitable hint of the strange looking bonsai pictured within. The trees in that book were more rugged, more contorted, more loose and freestyle than their Japanese counterparts. Many of them were stark in their appearance, with stripped-down foliage, almost minimalist in form. They were strange to my eyes, yet many of them captured an essence of something wild. Now I would describe many of those Chinese trees as naturalistic, although at the time I did not recognize them as such.

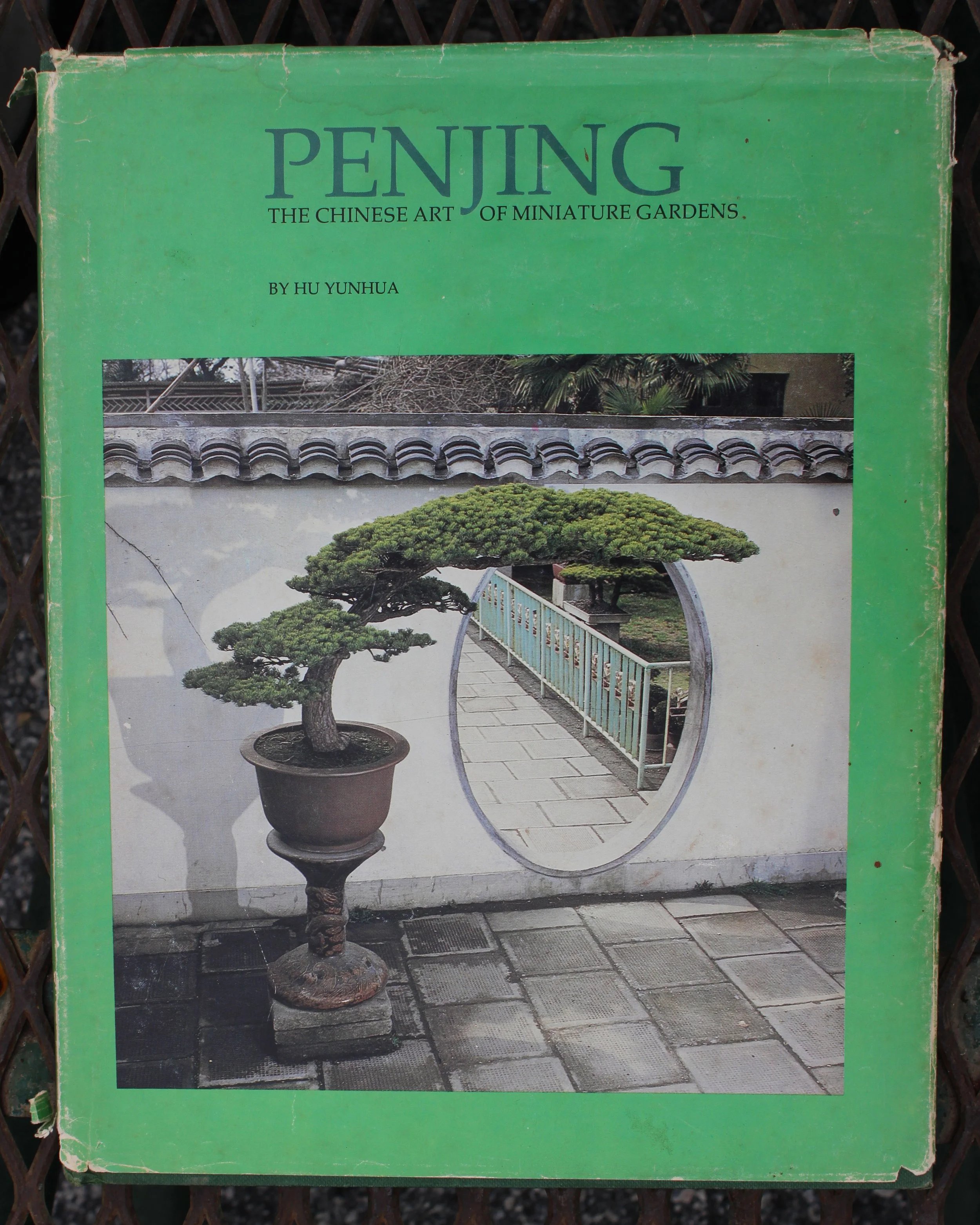

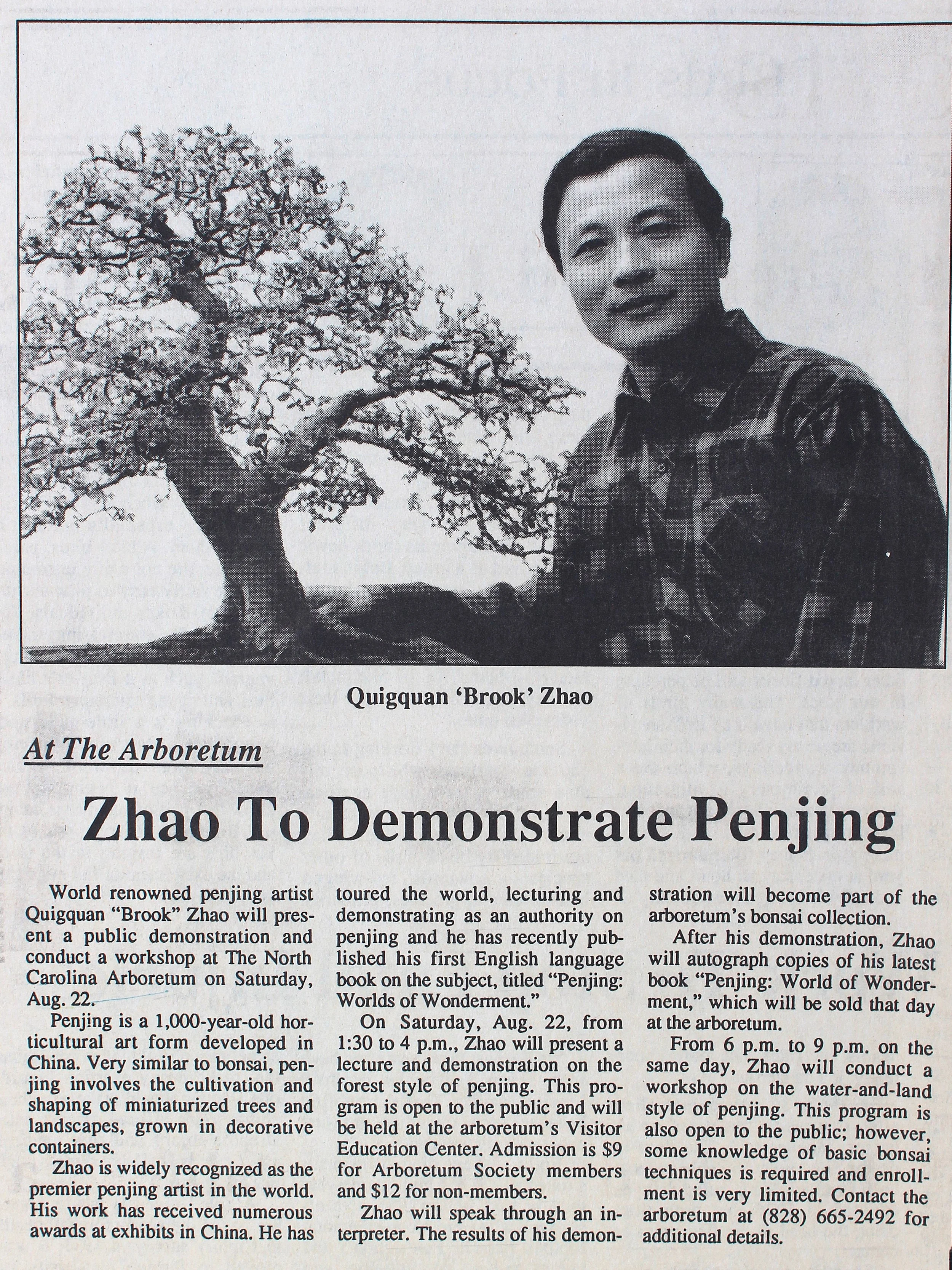

The other book was titled "Penjing, the Chinese Art of Miniature Gardens", produced by staff from the Shanghai Botanic Garden. In its pages were even more oddities, including trees resembling creatures such as elephants, trees with grotesque features, miniature trees presented as wall hangings, and miniature landscapes made out of pieces of rock or even charcoal, with little trees planted on them or sometimes without any plants involved at all. It was highly creative stuff, but it was absolutely not on the same page as the Japanese variant. I was striving to get a handhold in the world of American bonsai in the 1990s and as far as I could see, American bonsai was all in on the Japanese variant. I went with the flow in that direction. Yet something about the Chinese version remained intriguing. When the opportunity arose in 1998 to have a preeminent Chinese penjing artist named Qingquan Zhao visit the Arboretum, I eagerly went for it.

Qingquan Zhao was at that time the Penjing Master at Hong Yuan (Red Park) in Yangzhou, China. In America Mr. Zhao was best known in those days for one of his tray landscape plantings done in the water-and-land penjing style. The landscape depicted a scene wherein horses are resting in the shade of flowering trees, with picturesque boulders strewn about and a stream nearby. The trees were snow roses (Serissa foetida) and the horses were little handcrafted ceramic statues, realistically and artfully rendered. The stone was artful too, a special type called Turtle Shell Rock, and artfully used to suggest the outlines of a stream. The water of the stream was suggested by leaving the space for it blank, so that the white marble slab on which the scene was planted showed through. This penjing was titled: Painting With Eight Horses. The whole piece was excellent in its pastoral effect and it won a prestigious award at a top exhibition in China. Pictures of the penjing with the horses found their way into western bonsai magazines and people took notice. Mr. Zhao wrote a book, then started touring as a presenter and teacher. He adopted the familiar name "Brook" for the benefit of his western friends who found his first name unpronounceable. I've always thought of him and referred to him as Mr. Zhao out of respect, although I can't say his first name either.

Mr. Zhao's agent in the United States was also the publisher of his first English language book, Worlds of Wonderment. Her name was Karin and her publishing company was based in Athens, Georgia. I made connection with her through regional bonsai circles. She was at that time organizing an American tour for Mr. Zhao, so I arranged for the Arboretum to be one of his stops. I was keen to have him create a penjing landscape for our collection, but I wanted it to be something a little different and thought providing him with plant material native to our region might be an interesting wrinkle. We happened to have on hand a large number of baldcypress (Taxodium distichum), three or four years old and grown from seed, and Mr. Zhao agreed to work with them. He had never used baldcypress before and didn't really know much about them. He noted, though, that they were similar in appearance to dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), a tree native to China with which Mr. Zhao did have experience, and so he handled them in a similar way.

It was a big deal that we were hosting a guest artist from China. This happened during the period when I was pushing hard to promote bonsai's status within the Arboretum, so I did everything I could to play up Mr. Zhao's visit and maximize the benefit to the bonsai program. A press release was sent out to all the newspapers in our region, along with a publicity photo of Mr. Zhao. These were widely published. Attendance was very good for the Saturday afternoon demonstration, and all available spaces were filled for a penjing workshop offered later in the evening that same day. Mr. Zhao spoke little English, but the woman who was his agent acted as his interpreter and did an excellent job.

The baldcypresses we offered for the demonstration showed just a little variation in height and trunk size, being young and all the same age. Mr. Zhao asked if we had perhaps a larger baldcypress that could serve as the main tree of the composition. It was very important that one tree be clearly dominant. It happened that we had an acceptable candidate, a tree older than all the others by at least ten years, and Mr. Zhao used it as the focal point of his creation. The planting went on a large white marble penjing slab that we bought from an importer in Georgia. Mr. Zhao brought rocks from China and also a little fern-like plant he had picked up somewhere in his travels, to be used in the understory of the landscape. Mr. Zhao focused on his work with seriousness and intensity and was precise in his placement of every tree. He spoke little, making brief statements or giving brief answers to questions from the audience through his interpreter. Karin spoke well and was quite knowledgeable on the subject of Penjing and other facets of Chinese culture, so she provided an engaging running commentary throughout the program. The whole experience was educational.

The main tree, not from the same source as all the rest.

Mr. Zhao preparing for his demonstration program.

Mr. Zhao's program was very good and what it produced was even better. He had created, in miniature on a marble slab, the very image of a mature forest with tall trees and a stream running through it, complete with a lush understory and grey boulders. The boulders were actually stones Mr. Zhao used to delineate the stream bed, just as he had done in his famous Painting With Eight Horses landscape planting. Watching his program I learned this particular technique was the customary way of making water-and-land penjing. But saying the stones delineated the stream bed might be looking at the thing inside out. It’s a question of positive and negative space, because what the stones really did was form the boarders of two planting areas. The space between the planting areas was left unfilled and that emptiness is what suggests a stream that isn’t really there. Such is the artistry of this sort of creation.

Observing Mr. Zhao at work left no doubt in my mind as to his artistic legitimacy, and subsequent study of what he made that day was inspirational. It convinced me that while the Chinese way of bonsai is different from the Japanese way, it is in no way inferior. It is simply an alternative expression of the same creative impulse.

And if there are two distinctly different ways a thing might be done, doesn’t that suggest there could be other possibilities?

To be continued...

Qingquan Zhao’s water-and-land penjing featuring baldcypress, as seen on display at the opening of the Bonsai Exhibition Garden in October of 2005.