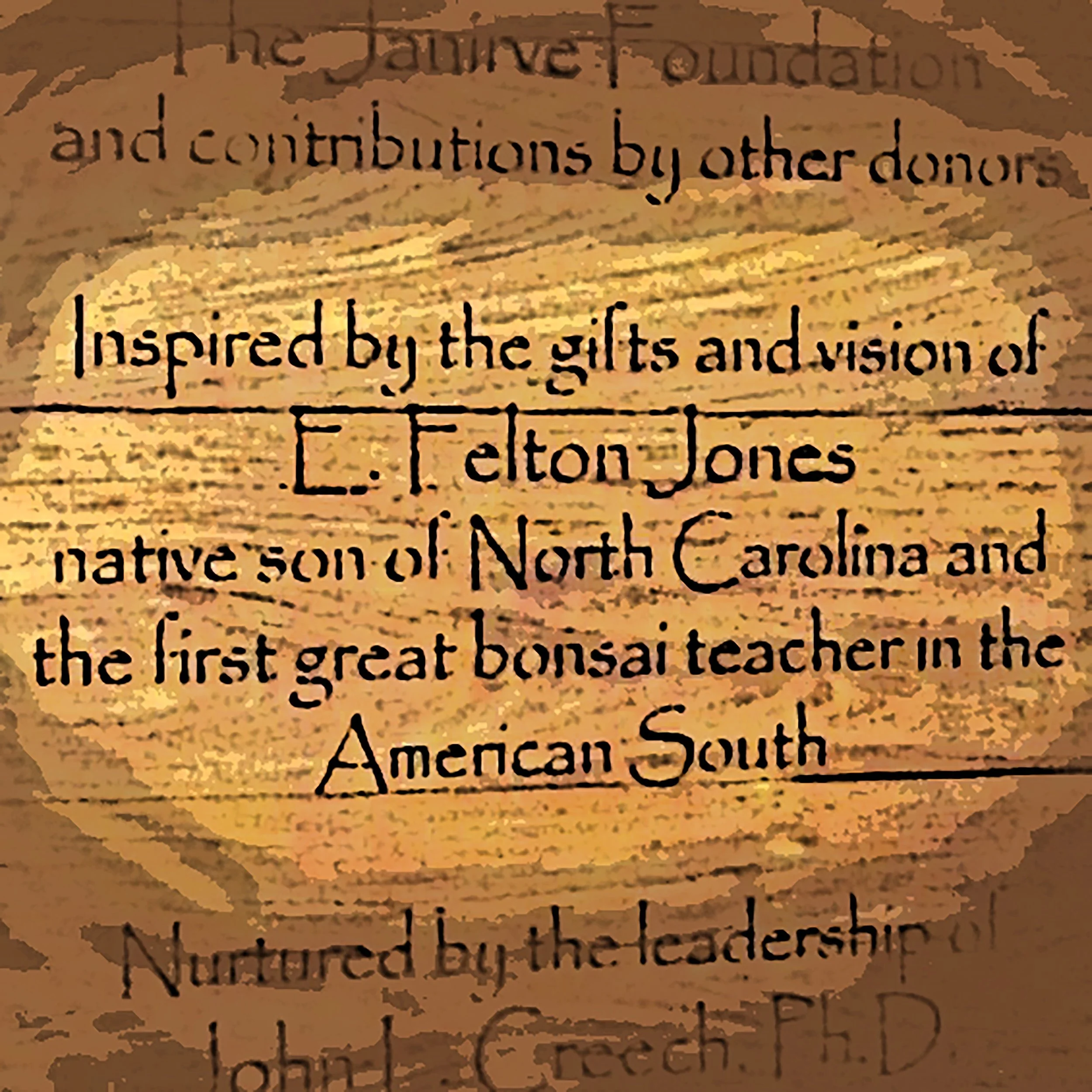

Felton - Part 4

Ten thousand dollars today is not what ten thousand dollars was twenty five years ago. Some of us may indeed still conceive of ten grand as a lot of money, but in the larger scheme of things that much cash won't take you as far as it used to. In early 1998, when Felton Jones offered ten thousand dollars to The North Carolina Arboretum, it resonated like a thunderclap out of the blue. To the best of my knowledge, to that date the Arboretum had only twice before received so much money in a single donation. What's more, the offer came from a person whom absolutely no one would have guessed had that much money to their name.

When I first heard of Felton's proposed donation I immediately assumed he must have reached out to some of those former students of his that he claimed were financially well-off and ready to help out if he asked them to. This proved to be an incorrect assumption. The money was Felton's, from a bank account apparently no one knew he had. Felton had squirreled away ten thousand dollars and even today I have no idea how he managed to do it or how long it took him to do it. He lived modestly enough to have saved some money over time, for certain, assuming that he had enough income to produce any amount of surplus. That's a missing piece of the puzzle. Regardless of how he did it, the ten thousand dollars Felton offered in donation represented his life savings — it was pretty much all the money he had in the world.

A couple of new characters in the story require introduction at this point. Harold and Tina Johnson were new to bonsai at the time and had recently found their way into the Triangle Bonsai Society in Raleigh, NC. Harold was in the insurance business and Tina was a teacher, and both were nearing retirement. They were looking for a new interest in which they might invest their time and attention once they reached that golden plateau, and they found bonsai. When they joined the Raleigh club they also found Felton Jones. The Johnsons were eager students and recognized that Felton was an outstanding local bonsai resource. They also happened to be kind people who recognized Felton's loneliness. They not only befriended him, the Johnsons more or less adopted Felton and acted in a manner similar to the way grown children might act toward an aging parent.

When Felton made his ten thousand dollar offer to the Arboretum he put himself at risk. Giving away his life savings was risky enough, yet danger lurked in another form, as well. The North Carolina Arboretum of that day was little more than a sprout compared to what it is today, and our primary intention then was to grow and develop. We were planning to do great things and we were hungry. Felton Jones was a humble old soul who was one way or another nearing the end of his wandering life. He emptied out his bank account and offered it to us, but did so with an agenda of his own. He wanted to see his beloved, all-important art of bonsai find a permanent home in this rising young institution. His great desire had found a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for fulfillment. Felton made his move and put his money out there with the implicit purpose of pushing the Arboretum to make a commitment to bonsai. It was an audacious move for a humble old soul to make.

Allow me the use of an analogy: Picture a frail old man with a rustic little row boat standing next to a stream. The stream is not very big but it is moving fast and has many snags, large rocks and other obstructions. From his place on shore the old man can look down the stream some distance and he imagines that somewhere beyond what he can see the water widens and the stream becomes a river, and the river eventually runs to a beautiful ocean. The old man wants his boat to make it to the ocean. He knows he'll not likely see the ocean himself but for some strangely compelling reason he really wants the boat to get there. What are the odds of success if the frail old man gets in the boat and pushes it out into the vigorous stream, with its powerful swirls and eddies, dangerous snags and rocks? The chances of the boat making it to the ocean are not so good in this scenario. The chances would hardly be better than if the old man shoved an empty boat into the swiftly moving water. Now, what would happen if two younger, stronger people climbed into the boat alongside the old man and helped to pull the oars and work the tiller? Even though the outcome would by no means be guaranteed, the chances of success would be substantially better.

That was the role the Johnsons played. They got into the boat with Felton and helped him navigate the dangers in the rushing water.

It's difficult for me to write about this part. Early on in my career I had to decide where my true allegiance lay — with the world of bonsai or with The North Carolina Arboretum? I wanted the two to become one and that's what I was pushing for, but the melding wasn't going to be easy because the two interests did not line up exactly. The Arboretum was my employer and had provided me a sorely needed opportunity, and I believed wholeheartedly in what the Arboretum had the potential to be. On the other hand, bonsai was a fascinating horticultural concept that also offered an artistic outlet, but came encumbered with certain features to which I just could not relate. I made my choice. My loyalty was then, as it is today, to the Arboretum. In the months following Felton's proposed donation, that loyalty was tested.

Introductions were made and meetings were held between the Johnsons, representing Felton, and several members of the Arboretum’s upper management. Felton's desire was simple — that the Arboretum accept his money and use it to establish a fund dedicated to building a permanent display facility for the bonsai collection. Felton wasn't specifically asking that a display facility be built, only that a fund be established for that purpose. The Arboretum knew as well as Felton did that establishing such a fund would be tantamount to agreeing to one day eventually build a bonsai facility. The same commitment that Felton sought was something the Arboretum strongly wished to avoid.

Why did the Arboretum wish to avoid making a commitment to bonsai? Here I must restrain myself from giving an opinion. The best I can offer is that the institutional reluctance to make a commitment seemed equally applied to all the various horticultural interests then viewing the Arboretum as a desirable place to be. None of them were making any inroads either. Bonsai happened to be the interest most persistently knocking on the door, and now Felton's proposal made that knocking much more difficult to ignore.

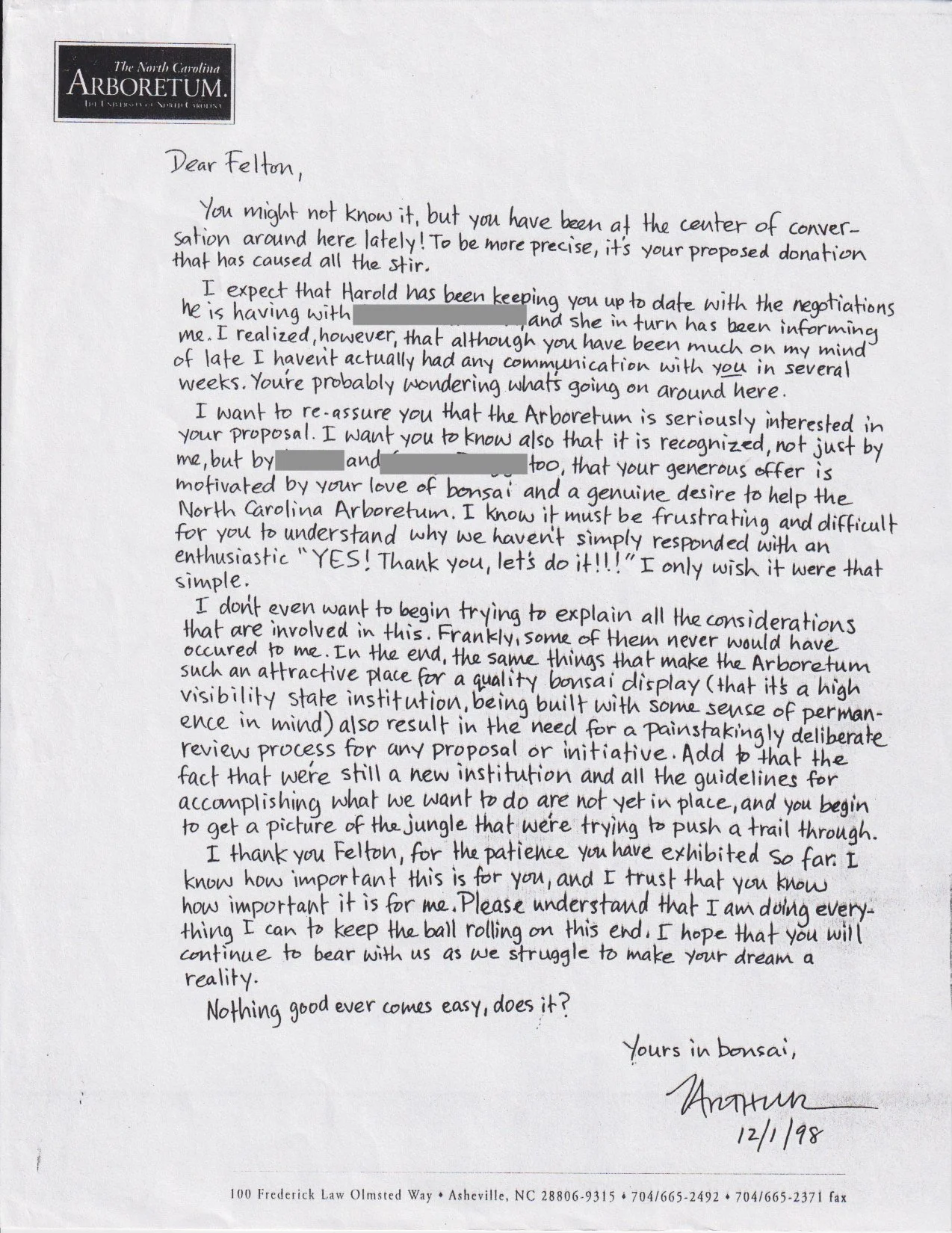

Negotiations went back and forth between the Arboretum and the Johnsons, acting as Felton’s agents. The Arboretum wasn't saying no, but also wasn't getting anywhere in repeated attempts to secure the offered money without making the required commitment. Frustrations were mounting on both sides of the fence. Felton wasn't in on these discussions and neither was I. The Johnson's kept Felton informed of developments and were the source of much of my information as well. As 1998 was nearing its conclusion with no progress being made, I felt the need to communicate directly with Felton in a tangible way to reassure him, just as I did whenever we spoke. On December first I wrote him the following letter:

Literally days later the Johnsons contacted me with news that Felton had issued an ultimatum. The Arboretum could accept his offer before the end of the year or he would withdraw it. We had less than a month to make up our minds.

To be continued...