Felton - Part 3

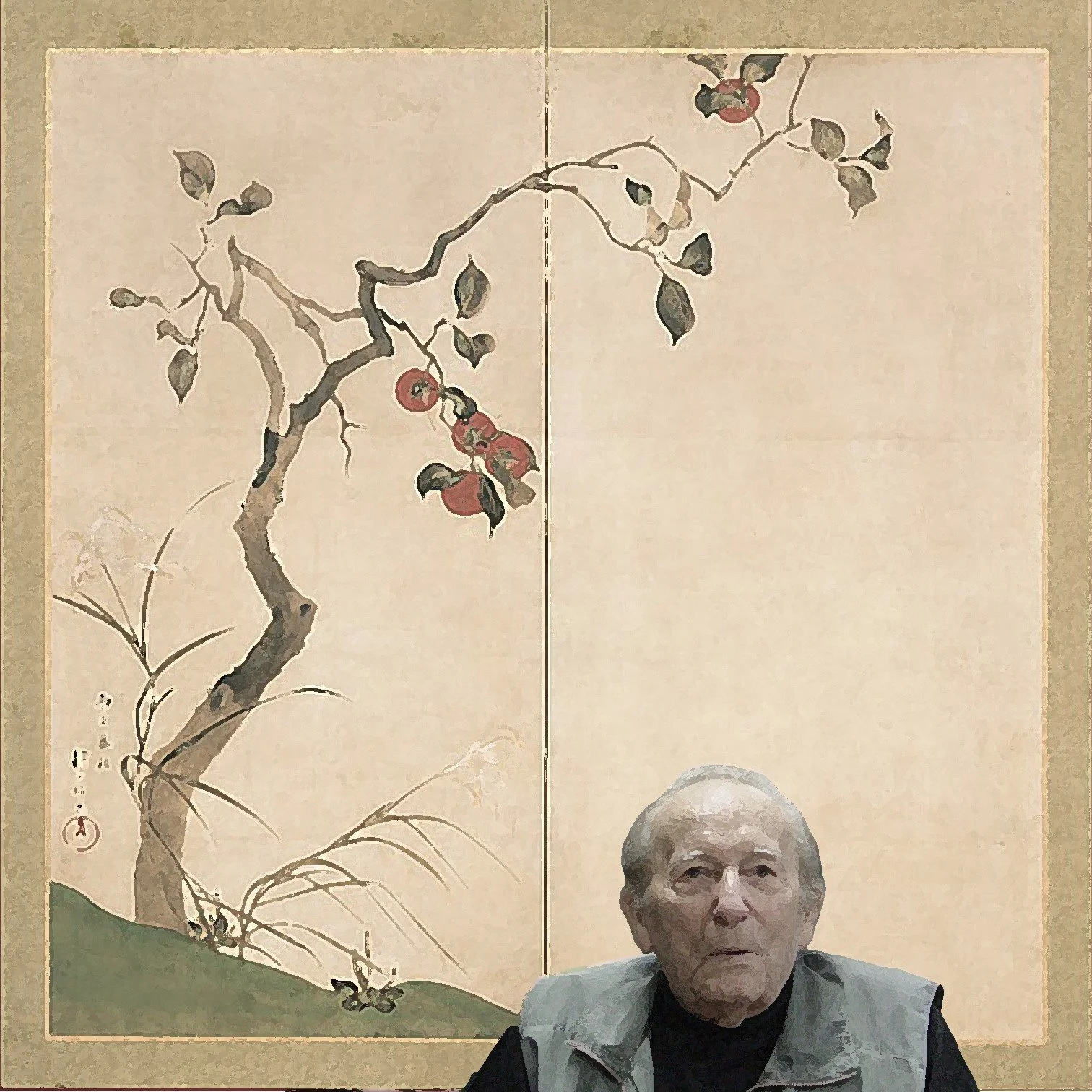

Felton was a wanderer in a sense that went beyond his penchant for moving about and living in different places. Felton had a wandering soul — or that was my impression of him anyway. He was a sensitive type of person who looked at the world differently than most folks. He moved to his own rhythms and they were slower and more thoughtful than most.

Nature was Felton's primary focus even before he came into contact with the Japanese-American community in southern California in the 1960s. Something in the old, traditional Japanese ways he learned there resonated with Felton and soon he was seeing nature through that lens. Bonsai captured his imagination in a visceral way. But he was also attracted to Japanese gardens and ikebana, Japanese sumi paintings of nature and Japanese haikus about nature. In fact, everything that might be construed as traditional Japanese appealed to Felton, whether it related directly to nature or not. Traditional in this usage refers to the old ways, the romantically pure, old and true ways from long ago before Westernization. It was as if Felton had wandered his way into a culture that made more sense to him than the one in which he was born, so he embraced it. Felton did the Tea Ceremony and wore kimonos onstage back in the day when doing his bonsai demonstrations. He would use the Japanese terms when he was teaching bonsai, then translate for the audience because that was all part of learning the art. You had to get into the right mindset if you wanted to do bonsai correctly, and that meant cultivating traditional Japanese sensibilities, and using all the proper Japanese terms. He certainly wasn't the only American bonsai teacher in those early years who taught that way, but Felton really took it to heart. He lived it.

Even at that early stage of the game I knew bonsai would never be presented that way at The North Carolina Arboretum. I had no attraction to the exoticism of that particular framing, and what's more, the Executive Director had told me himself that there was no place for bonsai at the Arboretum if it had to be identified that way. This was one of the relatively few things on which the boss and I saw eye to eye — bonsai was not to be an expression of foreign culture at this Arboretum. And where did that leave Felton Jones? Why, it left him off to the side, a curious but kindly old man, shuffling slowly, speaking softly, carrying about him his own air of a faded but better yesterday and bittersweet yearnings for a gentler, more poetic world. In short it meant that Felton didn't really have a part to play. He represented the old traditional view of bonsai, and we were aiming for something different.

Still, it was evident that Felton wanted to be involved in the development of bonsai at the Arboretum. His frequent visits and many gifts were testimony to that. Felton also acted as an ambassador of sorts. He still had many old contacts in bonsai circles and he was constantly promoting the Arboretum's emerging collection and program, encouraging others to get involved and lend support. Whenever I spoke with him, Felton would inevitably come around to the subject of a proper display for our collection. He had a vision of the Arboretum being a center for bonsai activity, not just for North Carolina but for the southeast region or maybe the whole country. That would never happen if the only place our visitors could see bonsai was in a hoop house out back of the production greenhouse, in a place far removed from the main area where all the action was. Felton made numerous suggestions about simple displays that could be built without having to spend a lot of money. He looked around at the Arboretum's four hundred-plus acres of mostly undeveloped woods and suggested that surely there must be someplace where a modest bonsai display could go without upsetting anyone. I tried to explain to him how things were at the Arboretum.

I was perhaps not the best person to do this explaining because I didn't fully understand it myself. The Arboretum of those days was dedicated to process and planning, and it was understood institutionally that nothing would happen on the ground until any given idea had been rigorously run through the ringer of process and thoroughly planned out. Management was taking the long view. Decisions were made with exhaustive deliberation, to the extent that some people outside the process found it difficult to see that anything was happening at all. The core garden area had been built and unveiled to the public in 1996, and among much of the regional horticulture community the response had been tepid. They saw great expanses of pavement and very little in the way of plantings. There was mounting demand from people in various plant societies who wanted to know when the Arboretum would start building collections. When would we have a rose collection, or a daylily collection, and when would we start planting trees of all different species so we could do what an arboretum is supposed to do? When would we start a plant breeding program so we could trial new cultivars for the green industry? There was a lot of expectation. It had been ten years since The North Carolina Arboretum had come into existence on paper and some people were getting impatient about the rate of progress it had thus far shown.

My position was on the inside of the Arboretum, but I was working on the ground, literally, and not sitting in any of the offices or meeting rooms where institutional strategy was being formulated. I knew about the importance of process and planning because all of us working at the Arboretum had been told about it, repeatedly. Even so, I sympathized with the people who felt like more should be happening plant-wise. Some of those discontented members of the green public were friends of mine and some were people from the bonsai community, so I was often questioned about why the Arboretum was not more aggressively pursuing its horticultural mission. I toed the company line and explained that all the good stuff was coming but we wanted to do it right. Building an institution of the kind the Arboretum intended to be, starting from nothing, was no easy lift. We didn't want to do anything in a hurry that might have to be undone a few years down the road. We wanted to be thoughtful about everything and build something great that would last.

I told Felton all that stuff, more than a few times. He listened patiently, never arguing about it, although he would sometimes point out that he was an old man and his health was not the best so he wondered if he would live long enough to see this dream of his come true. One time Felton told me that he knew some people of means who had been students of his, and these people would be glad to support a fundraising effort dedicated to building a bonsai display area if he asked them to. I told Felton I appreciated that, but the Arboretum wasn't soliciting funds for such a thing. I didn't think it would work out so well if people tried to pressure the Arboretum administration into doing something it wasn't committed to doing in the first place. Besides, the amount of money necessary to build something that would measure up to the Arboretum's standard would be substantial. "How much?" Felton said. "I don't know," I said. "A lot would go into it. There would be a whole detailed planning process and depending on what came out of that there would be a cost estimate. Felton," I said, "it's not going to be a few thousand dollars. It's going to be tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands."

"Oh my," said Felton, and he fell silent.

Not long after, word reached me of a startling development. Felton Jones had offered a cash donation to the Arboretum on condition that we use the money to establish a fund dedicated to building a display space for our bonsai collection.

Oh no! That poor old guy has no idea what he's done! How much could he put up for this — a hundred or two hundred dollars? This is bad. This is going to cause problems. I wish he hadn't done it!

With trepidation I asked how much Felton had offered. The answer came back: Ten thousand dollars.

To be continued...